Following a career as a newspaper reporter, Dori Maynard took the helm of the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education. Founded by her father (1937–1993), it has trained thousands of journalists of color

My father was so eager to begin his life as a journalist; he left high school at 16 to become a freelancer. His Nieman year was the academic experience that validated his intellectual acumen. It became his university and his fraternity. He became its evangelist. To this day, I run into people who tell me my father pushed them, coached them, or helped select them to be Niemans.

Harvard was where he studied music, art history, urban politics and economics. It was where he met Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee. In a piece in the Post after my dad’s death and later in his biography, Bradlee described their first meeting: “He stood out in the crowd. Not only because he was black … but because he was confrontational, argumentative, mean and skeptical, verging on the obnoxious. Much of my ninety minutes with the Niemans was spent arguing with Maynard.”

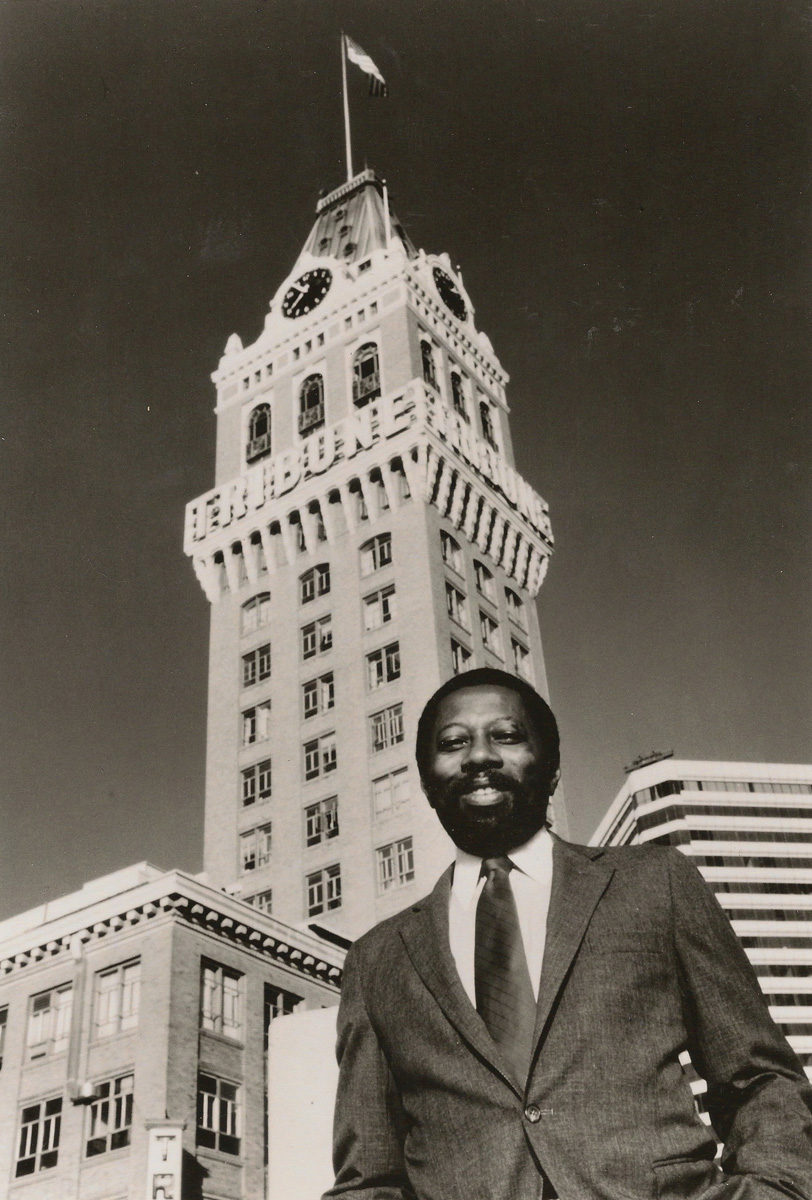

Many of my father’s friends disputed that account, arguing it was uncharacteristic of the charming, charismatic man they knew. No one disputes the results of that meeting, though. Bradlee hired my father, and my father used much of his grounding in economics and urban politics to cover the urban unrest sweeping the nation in the late 1960s and ’70s. It was that grounding that helped him understand the promise of Oakland, California when he moved out there, first to be the editor of the Oakland Tribune and then the owner.

He passed that love of urban politics and policy on to me as we walked through cities, once from Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn to the Village in Manhattan, him talking the entire way about the pressures, policies and politics that shaped each neighborhood. Years later, when I became a Nieman, my father, who had chafed at the male-only composition of classes during his time, reveled in the fact that we were the first father/daughter Niemans.

I came from the Detroit Free Press and focused on politics and poverty, fascinated by the gap between the people who made and discussed policy and the people in Detroit who lived with poverty. When I visited for Christmas, my father told me about his latest project, Fault Lines, a tool to help journalists identify and examine the perceptual gaps shaped by race, class, gender, generation and geography. It was a project perfectly suited to frame the remainder of my Nieman year, as I continued to explore the ways in which policymakers are divorced from the people they purport to serve. That continues to frame the work I do to this day.

It was also a project that gave us the opportunity to work together and share our respective Nieman experiences in the only way we could. For by then, too ill to travel, my father was unable to visit during my Fellowship year. But on one of the waning days of his life, he sat in his hospital bed looking at our Nieman certificates, framed side by side.