Ulanovsky was inspired by his Nieman year to foster journalism that is intensely personal

I had a good job with one of the most widely read Spanish-language newspapers in the world, Clarín, in Argentina. But I felt uncomfortable about publishing information that did not translate into real communication with readers. We talked about what was happening, not about what was happening to us. Though journalism supposedly reflects the world in all its complexity and, sometimes, obscurity, I felt I was only able to engage determined spheres—politics, economic trends, social movements. There is more to convey, I thought, though I was not sure how. During my time as a Fellow, I found markers that helped me pursue an answer.

I enrolled in a course given by psychiatrist Arthur Kleinman on the anthropology of pain.

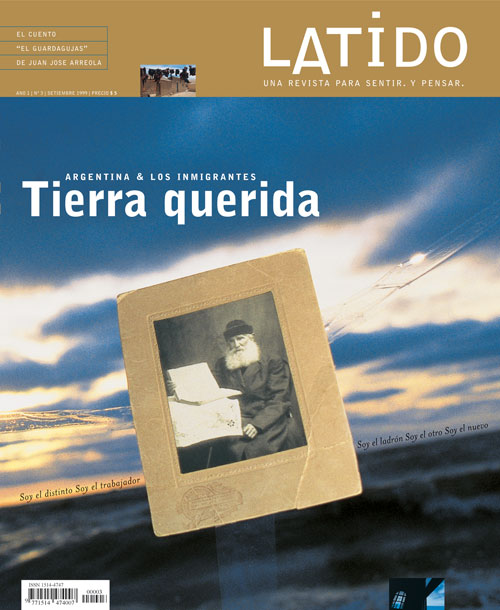

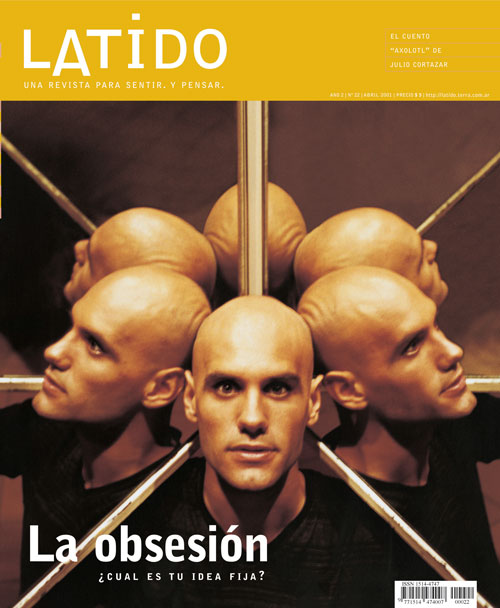

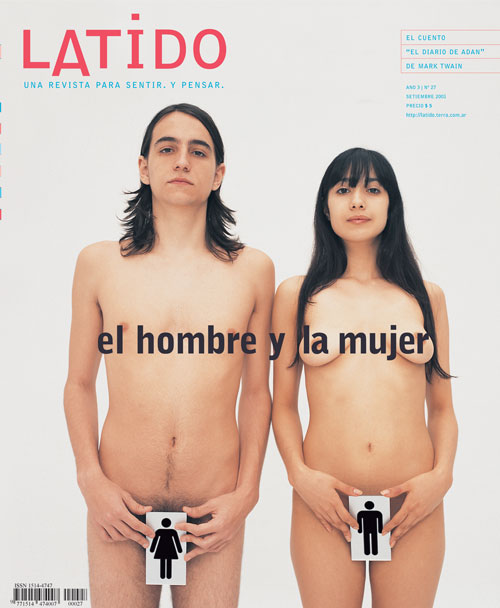

Latido, a magazine of first-person journalismThe class addressed topics like what is painful and how discomfort is experienced in different cultures. It was a revelation to break out of the logic of mass journalism and venture into the workings of the individual. I was similarly startled by the revolution brought on by Rose Moss’s class in creative writing, where I learned to heighten the psychological sensibility of a story.

After the Fellowship, I came back to Buenos Aires and one afternoon it hit me: Why isn’t there a journalism of private life that deals with daily experience? Three years later, I launched Latido (Heartbeat), a monthly magazine of first-person journalism in which the narrator has actually experienced what he or she is reporting. A journalist with a drinking problem, for instance, speaks of the complexity of addiction. A journalism of personal space began to take shape.

Two years ago, I returned to Clarín to lead a project around whether the mass media can—and should—generate spaces for communication through “intimate worlds,” which is also the name of a weekly section that embodies a journalism of lived experience. We don’t speak of the effects of torture on nameless people incarcerated during Argentina’s last military dictatorship; we hear from a woman who was “disappeared.” We reflect reality through how it operates in specific experience. There was something of all this at work that year at Harvard. Sometimes we don’t know where we are going until we get there.