Sancton (1915–2012) wrote about the nascent civil rights movement in the 1940s

The award of a Nieman Fellowship in 1941 was a turning point in my father’s life. It sent him to a prestigious university and convinced him that he was sufficiently launched on a career to marry his sweetheart, Seta Alexander, daughter of a prominent family from Jackson, Mississippi. They were married in December 1941 and moved to a little rented apartment off Harvard Square.

At Harvard, my father took courses in Russian literature and Southern history, including Paul Buck’s history of Reconstruction. He talked about dinners and lively discussions at the Signet Society, where he once had a heated argument with Robert Frost over the poem “Mending Wall” and the misanthropic implication of the line “Good fences make good neighbors.” His Nieman experience was an important landmark in his sense of himself as a serious journalist and writer, someone who could perform at the highest level of his profession.

The Nieman was also instrumental in determining my father’s future career path. In early 1942, New Republic editor in chief Bruce Bliven was shopping around for a new managing editor. Professor Buck and Nieman curator Louis M. Lyons recommended Sancton, who was offered and immediately accepted the job. Sancton continued to cherish his connection with Harvard, even referring to himself on occasion as a “Harvard man” and convincing me, Tom Jr. (Harvard 1971), that the university was a family tradition.

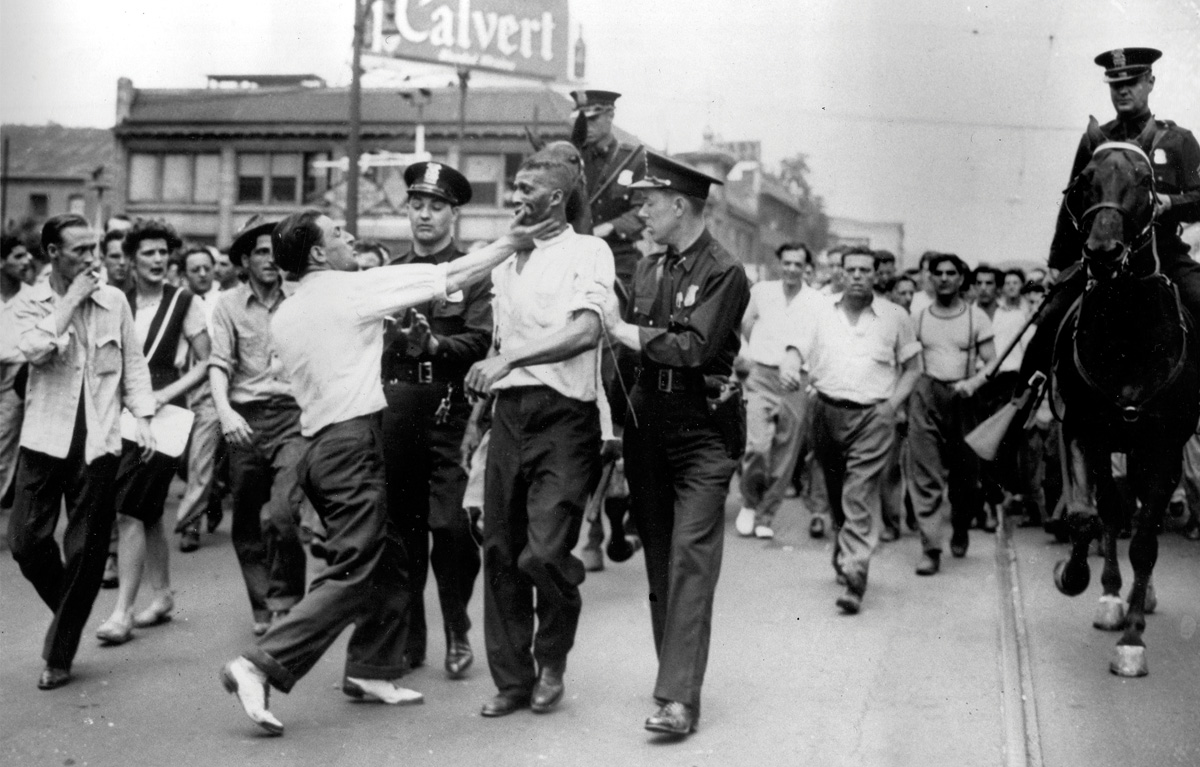

Working for a liberal publication like The New Republic enabled Sancton to write about the subject he was most passionate about: racial justice. Voicing personal convictions that were rooted in his New Orleans childhood (but hardly typical of his fellow Southerners), he attacked segregation and racial inequality in a barrage of incendiary essays and editorials that won him the admiration of the liberal intelligentsia and black leaders like W.E.B. DuBois while provoking the wrath of Southern segregationists. John Rankin, a white supremacist Democrat from Mississippi, even denounced Sancton’s articles on the floor of the House of Representatives, a fact that Sancton considered a badge of honor.

Throughout the years, he remained devoted to the Nieman program and managed to steer several younger journalists to Cambridge with enthusiastic letters of recommendation and phone calls to Lyons. Among his Nieman “protégés”: Charles A. Ferguson, NF ’66, former editor of the New Orleans States-Item, and Philip Johnson, NF ’59, former news director for WWL-TV, the local CBS affiliate.

By Tom Sancton Jr., former senior editor and Paris bureau chief for Time