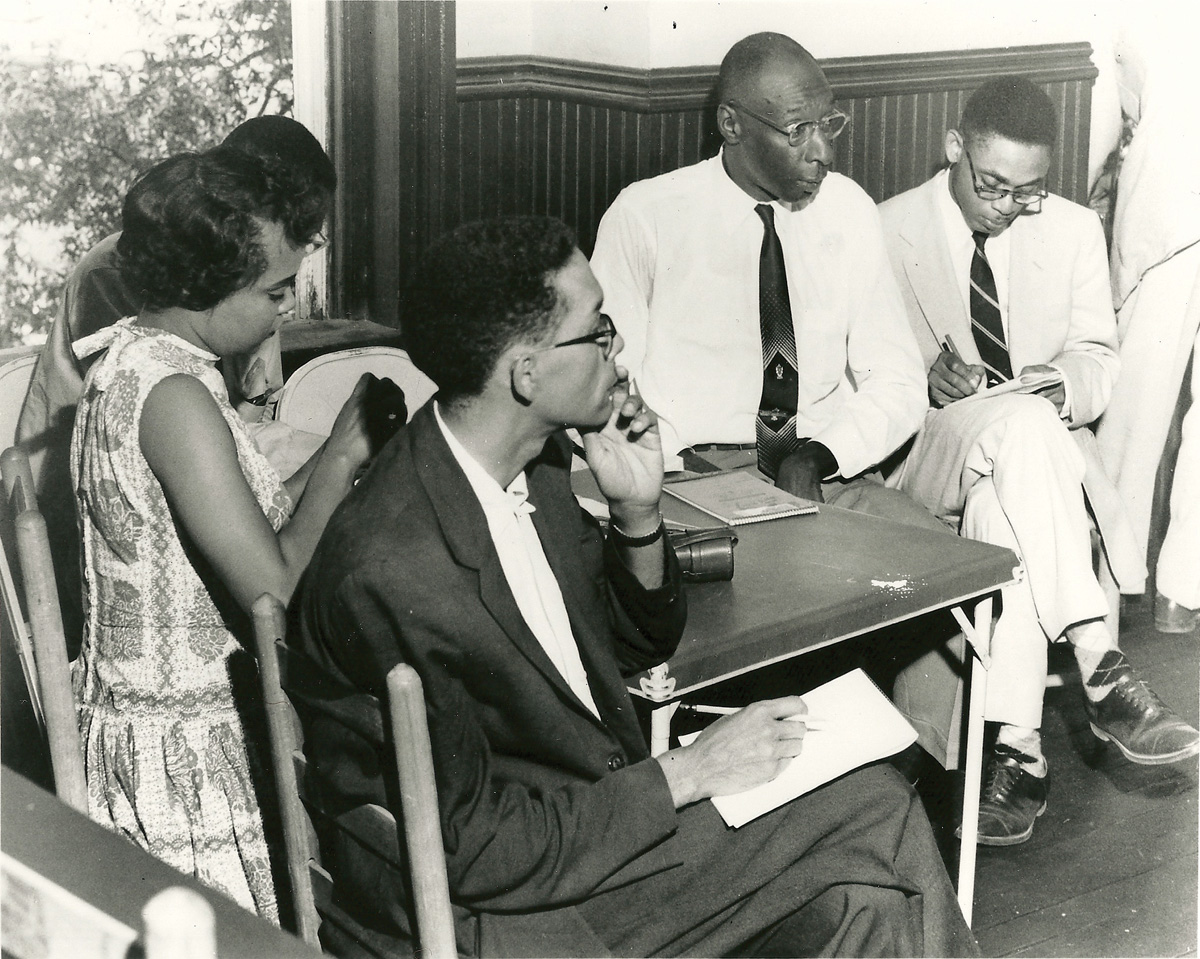

Working for Jet magazine, Booker covered the civil rights movement for 53 years

The Nieman program under Louis M. Lyons was eons ahead of the nation’s press when it came to race relations. In 1950, when I became the second black Nieman Fellow, only a couple of dailies in the entire U.S. had ever hired Negro reporters. No retreat into an ivory (or ivy) tower, the Nieman year was replete with roundtables, conferences with professors, cocktail receptions, speakers’ dinners, and a whole melange of social mingling among the Fellows, staff and faculty. The lack of any racial tension or segregation—indeed, the camaraderie!—was itself a career-changing moment for me.

On the first night of the Emmett Till trial, in which two white men who admitted kidnapping the 14-year-old black youth were charged with his murder, Clark Porteous, NF ’47, a reporter for the Memphis Press-Scimitar and a classmate of the first black Nieman, Fletcher P. Martin, defied Mississippi’s segregation laws by visiting with black reporters. He told us that the prosecution had no murder witnesses and no forensic evidence to support a guilty verdict.

That night, a local civil rights leader learned that there were witnesses who were afraid to come forward. A plan was devised to find them, guarantee their safety, and urge them to come in, but it required someone to notify law enforcement and the prosecution. We agreed that a reliable member of the white press should be asked to act as the go-between, but the civil rights leader trusted only one out of the dozens attending the trial. I agreed with his choice: Clark Porteous.

The following night, Porteous and I followed the sheriff of Leflore County and NAACP field staff on a 70-mile-an-hour manhunt across plantations to bring in the frightened witnesses. Although the trial still ended in acquittal, the murder and everything about it had a galvanizing and enduring impact on the civil rights movement, which in turn changed everything about life in America, including its journalism.