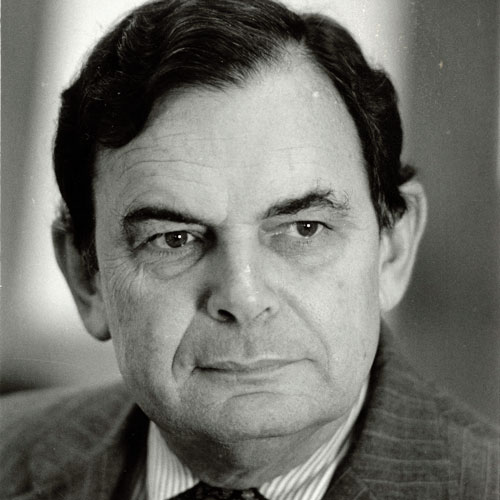

Roberts worked as a reporter in North Carolina before becoming the chief Southern and civil rights correspondent for The New York Times after his Nieman year. He is co-author of Pulitzer winner “The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation.” During his 18 years as executive editor of The Philadelphia Inquirer, the paper won 17 Pulitzers

When I arrived at Harvard in the autumn of 1961 to start my Nieman year, I expected to learn much more than I knew about American history, but was dubious about whether Harvard would have much to offer on the subject I most wanted to cover in my newspaper career—segregation and racial discrimination in the Southern United States.

Nevertheless, I enrolled in Dr. Thomas Pettigrew’s social psychology class, the closest thing I could find to a civil rights course at Harvard. Within days, I found myself deep in conversation with his teaching assistant. I told him I had covered the segregationist candidate in an intense gubernatorial campaign in North Carolina against moderate Terry Sanford, who won by a comfortable margin.

He wanted to know if the counties that voted for the segregationist were scattered or fell for the most part in a grouping. Mostly a grouping, I said. He thought he could tell me which these were by feeding two bits of data into what was then a primitive computer. The data? Soil content and population growth, if any, in the counties’ towns. I laughed at his audacity.

A few days later, he brought in a list of counties that had voted heavily segregationist. I didn’t laugh. He missed by only one county.

My mind opened wide in ways I never expected … I put the numbers of several social psychologists in my notebook. I called them frequently

How did he do it? Segregation was most rigid in counties with rich black soil. This was where cotton thrived best and where the planters needed the most slaves. Often African-Americans outnumbered whites in these counties; whites maintained control by restricting or banning black voting and strictly enforcing segregation laws. These counties across the South were collectively known as the Black Belt, not for the black population but the black soil content. The only time black soil would not predict racial attitudes was if a large urban area had grown up in a county and large numbers of “outsiders” had flooded in.

My mind opened wide in ways I never expected. I read Gunnar Myrdal’s “An American Dilemma” and W.J. Cash’s “The Mind of the South” with new intensity. Later, when I became The New York Times’s chief Southern correspondent in the mid-1960s, I put the numbers of several social psychologists in my notebook. I called them frequently.