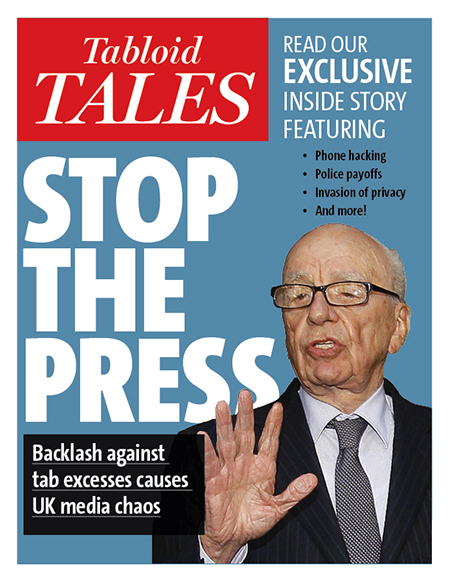

Photo of Murdoch by Kirsty Wigglesworth/The Assoicated Press

On a late March afternoon in 2002, 13-year-old British schoolgirl Amanda Jane “Milly” Dowler called her dad from her cell phone after school to say she was about to start the half-hour walk to their home. Somewhere along that walk, she disappeared. During the six months before her body was found the case became the focus of frenzied tabloid news reporting. There was fierce competition to publish details about the police investigation, Milly’s personal life, her family, and speculation about possible suspects.

It took another nine years for her murderer to be caught, tried and convicted. And within months of that conviction, there was a further twist. News reports revealed that journalists from Rupert Murdoch’s News of the World had illegally listened to voicemails left on the missing girl’s cell phone during the police investigation.

This was an outrage too far for a public grown accustomed to the worst excesses of Britain’s tabloid journalists. The tabloids’ irreverent attacks on the rich, the famous, and the establishment, led mainly by Murdoch’s Sun and News of the World titles, were much enjoyed by readers who tended not to be on the receiving end of the caustic coverage.

That changed with the Milly Dowler phone hacking disclosure. And it triggered a process that has led to a political showdown between the country’s newspapers and a government trying to rein in tabloid excesses.

In March, the coalition government of Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron, with the backing of the other two main political parties, proposed a system of press regulation, something not seen since Parliament abolished press licensing at the end of the 1600s. The plan would create potential punitive fines for newspapers that don’t join the system, allow the regulator to dictate how newspapers must handle corrections, make members pay for their own self-regulation, and couldn’t be changed without a two-thirds majority vote of Parliament.

Press freedom advocates around the world, including Index on Censorship, the Committee to Protect Journalists, the World Association of Newspapers, and The New York Times, condemned the idea as chilling to a free press. Within weeks the majority of the U.K.’s newspapers and tabloids, excluding only The Guardian, The Independent, and the Financial Times, rebelled, announcing they had agreed on their own self-regulation system. Regardless of which—if either—plan is adopted, one thing is clear: A decade-old phone hacking case has brought to light hidden relationships among the police, the press, and politicians.

Phone hacking is illegal in the U.K., but the laws aren’t enough or aren’t doing the job, claim many sectors of British society. The tabloids stand accused of checkbook journalism, police payoffs, bribery, blackmail, invasion of privacy, political manipulation, and the publication of false information at will. Britain’s high court costs and libel laws, while recently reformed and much improved, make it both difficult and expensive to sue big newspapers with deep pockets and powerful legal teams. In the U.K., politicians, business leaders, sports stars, and celebrities are seen as fair game for a tabloid press that is as widely reviled as it is widely read.

As in the Milly Dowler case, average citizens can also become fodder for tabloid intensity. Those who complain or criticize the coverage can find they are subjected to even greater scrutiny. British actor and comedian Steve Coogan was one of those who testified to the Leveson Inquiry, the parliamentary commission set up to investigate the phone hacking. He told the hearing that a tabloid journalist had tricked one of his elderly relatives into answering personal questions by pretending to be a government researcher. He had also watched tabloid journalists dig through his trash. The day after he appeared on a BBC show criticizing these tactics a flurry of intrusive articles about him appeared. These tactics are not uncommon. Scotland Yard said that its investigation into phone hacking cases now numbers more than 2,500 victims.

The U.K. has had some form of voluntary press self-regulation since 1953, including the Press Complaints Commission (PCC), which was formed in 1991. All have been seen as ineffective, and the PCC has been lambasted as “toothless” for doing nothing in the face of the News of the World phone hacking scandal.

The first phone hacking case surfaced at the end of 2005 when Buckingham Palace reported to Scotland Yard its suspicions that someone was illegally gaining access to voicemails on a cell phone belonging to Prince William, the second in line to the British throne. The police investigation led to the arrest, conviction and jailing of a News of the World journalist and the private investigator who gained access to Prince William’s messages, and to the resignation of News of the World editor Andy Coulson in January of 2007. Rupert Murdoch said it was an isolated event. The PCC carried out two investigations, in 2007 and 2009, and concluded the same. Case closed.

But dogged investigative coverage by The Guardian, joined by The New York Times and then other British news organizations, continued to pick away at the hacking story. On July 4, 2011, The Guardian reported that the News of the World had illegally gained access to the voicemails on Milly Dowler’s cell phone in 2002, while she was still missing, and used that information in its stories. “Rarely has a single story had such a volcanic effect,” wrote The Guardian’s editor in chief Alan Rusbridger in the e-book, “Phone Hacking: How The Guardian Broke the Story.”

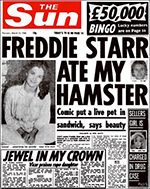

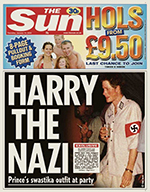

Classic Sun headlines, from top, take aim at a U.K. comedian (1986), a European Union leader (1990), and Prince Harry (2008)

Within weeks, Murdoch shut down the News of the World, the largest circulation Sunday newspaper in the U.K., as advertisers abandoned the publication in the face of public fury over the Dowler phone hacking revelation. Former News of the World editor Coulson, who had worked as Cameron’s top media adviser from 2007 to January 2011, was arrested. Rebekah Brooks, the former editor of both the News of the World and The Sun, resigned as CEO of the newspapers’ parent company, News International, and was also arrested. Two Scotland Yard police chiefs resigned. Murdoch was forced to withdraw his bid to take a controlling stake in British Sky Broadcasting (BSkyB), a satellite and broadband company.

The scandal was not limited to the Murdoch press; other tabloids deployed similar hacking tactics. But it was the scale and targets of the News of the World hacking that shocked even those who suspected it was happening. Cameron ordered a parliamentary investigation into the hacking charges and a second inquiry, a much broader one, to consider “the culture, practice and ethics” of the British press. The man tasked to lead the latter inquiry was Lord Justice Sir Brian Leveson.

For almost a year, the country watched fascinated and sometimes horrified as around 400 witnesses gave testimony in televised sessions. Witnesses included Murdoch, Brooks, Coulson, and Milly Dowler’s parents as well as dozens of journalists from most of the U.K. newspaper industry. Many politicians, including U.K prime ministers past and present—Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, and Cameron—testified. Police and private investigators appeared before the inquiry to be grilled about accusations of widespread payment by tabloids to police to provide them with citizens’ private information or details of ongoing investigations.

In his final report, delivered last November, Leveson said that the U.K. press had too long “wreaked havoc in the lives of innocent people.” He criticized the cozy relationship between powerful newspaper editors and politicians and called for more transparency in their contacts. He recommended an arbitration panel as a quicker, low-cost, first stage to resolve privacy and defamation complaints. These were all broadly welcomed suggestions.

But at its core the report calls for press self-regulation “with teeth.” The way to add teeth, Leveson said, was to enshrine the media’s “self-regulation” in legislation. Glaring in its absence is any reference as to how Internet publishing, social media, or mobile journalism might, or should, be affected. The expectation was that the newspaper industry would agree how to implement the recommendations. That process quickly became mired in political maneuvering, so Cameron decided to draft his plan, which was in turn challenged when newspapers revealed their own scheme. The alternative proposal by newspapers eliminates the role of the government in the regulation process, allows editors to sit on the regulatory panel, and withdraws the power of the regulator to direct corrections. Either proposal would require government support.

“It’s a mess which now relies on political compromise; never a good position to be in,” says Richard Sambrook, former director of BBC World Service and Global News and current director of journalism at Cardiff University. “I think the tabloids will behave for a bit but commercial pressures in the end will push them back towards impact at any price. In the long run, I think the press will be a bit more restrained for a few years, but I’m not sure anything very much will change.”

Tabloid journalists continue to be investigated and arrested as part of the ongoing Operation Weeting by Scotland Yard into phone hacking. Two separate police investigations are focusing on computer hacking and illegal payments to police by newspapers. There have been no trials or convictions on the phone hacking charges other than the original two convictions in 2007. Brooks and Coulson are scheduled to go on trial this fall. Murdoch himself seems to have emerged unscathed, at least commercially, apart from the abandoned BSkyB bid. Less than a year after he shuttered the News of the World, he turned its sister paper, The Sun, into a seven-day-a-week operation. It is now the biggest-selling U.K. Sunday paper.

The Surrey police who investigated Milly Dowler’s disappearance were aware at the time that the News of the World had hacked her phone. A report by the Independent Police Complaints Commission, a watchdog organization, said there “was no doubt” that police were made aware of the hacking and yet not only failed to act at the time of the investigation, but also failed to speak up five years later in 2007 when the News of the World claimed that the hacking of the royals’ cellphones was an isolated incident. The police also failed to speak up as additional hacking charges were made until July 2011. The report said the former senior officers involved in the investigation were afflicted by a “form of collective amnesia” and highlighted an “unhealthy relationship between the police and the media.” It reported one officer as saying that the silence was an effort to “keep the media on side.”

Fear is the common theme running through two years of revelations about tabloid excesses. Police, politicians and the public have been cowed, corrupted and silenced by their fearsome bullying tactics. The Leveson inquiry was payback, finally making public what so many were previously afraid to say out loud. Ironically, fear is now driving the confused, chaotic efforts to regulate the news industry. Press victims and advocacy groups like Hacked Off fear losing the momentum Leveson has given them; politicians fear losing the support of voters outraged by dirty press tricks. As yet, though, only a few Britons seem afraid of what might happen if politicians start regulating news publishing, online and in print.

Katie King, a 1994 Nieman Fellow, is director of studies, Cardiff University School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies. King is also a trustee of Index on Censorship, which has criticized the Parliament-approved press regulation plan.