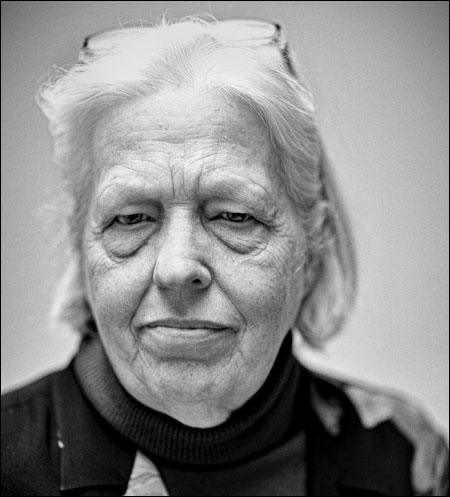

Photo by Timothy Archibald.

The news stories Sandy Close remembers coming out of Oakland, California, RELATED ARTICLE

"The voice on the other end of the line"

- By Kimberly Frenchin the mid-1980s were horrific: Kids driving a truck over an already-dead body, or even biting the corpse. The media were calling them "superpredators." Weekly newsmagazines were declaring the death of cities. Close, who was executive editor of Pacific News Service (PNS) at the time, could not accept what the mainstream media and its experts were saying.

She knew Oakland's inner city intimately, going back to the 1960s, when she founded a paper called The Flatlands to serve poor neighborhoods. "People like Bill Moyers, for Chrissake, were saying the morals have left the city," she says. "It wasn't morals. It was white people who turned their backs on it, leaving an economic vacuum."

That moment "transformed my idea about what I do as a journalist," says Close, who now directs New America Media (NAM), a news and communications service started by PNS in 1996, which has more than 2,500 ethnic-media members in print, radio, television and online. In December, the Nieman Foundation awarded Close the I.F. Stone Medal for Journalistic Independence "for giving a voice to individuals and communities too often ignored by mainstream media."

Appalled that young people were being demonized but weren't even part of the discussion, she organized forums to find out what they had to say. "The amazing discovery for us was that young people felt they had no way to make their mark, to be visible, and that was fueling the violence," she says. Whether parents were in jail, on drugs, working 80 hours a week, or simply absent, young people were growing up in empty houses, without intimacy. They wanted to be seen.

Calling the forums "oral journalism," PNS invited state legislators, researchers and funders to hear young people on topics like race relations and immigration. "The people who understood it best were young people, who were growing up with it," Close says. "Young people are fascinating to me, especially when they are on the edge of the culture, because they represent who we are becoming. And what we are becoming is a deeply fragmented, fractured society." Those forums revealed, for example, that a sizable percentage of Mexican migrants were indigenous people who didn't speak Spanish, a fact few people knew at the time.

Finding the unheard voices and then teaching them to tell their own stories has become the real prize for Sandy Close. She realized something was missing in the work at PNS. She wanted the young people she was bringing to the forums in the office. "Why shouldn't the street be in the office, and the office in the street, and not just when something bad happens?" asks Close, who grew up reading the (New York) Daily News on the subway. "It gets closer to what journalism used to be, a mirror of the city that helps me understand, Where do I fit in all this?"

In 1986, PNS launched a youth page, published in The San Francisco Examiner, which later grew into the magazine Youth Outlook and Youth Radio. The tiny office packed in 20 to 30 youths at a time working as contributors—coming to editorial meetings, out reporting, writing and producing stories. At times, it was a strain. But knowing young people, going to birthday parties and baptisms, gave her journalists an amazing entrée into the city.

She hunted out raw, authentic first-person voices, training hundreds over the years to tell their own stories. Charles Jones, a homeless ninth-grade dropout, became one of her most brilliant writers. A.C. Thompson was a tattooed, unemployed vocational-school grad who cared only about extreme metal and couldn't put together a sentence; last year he won the Stone Medal for his ProPublica exposés. Her stable has produced names like Renee Montaigne, who went on to NPR; John Markoff and Julia Preston to The New York Times; and David Talbot and Joan Walsh to Salon.

One colleague compares Close to a mother hen, hatching writers and news organizations and sending them out across the country. There is something of the warm but tough parent in Sandy Close: soft-spoken yet authoritative, hawk-eyed and always questioning, nurturing while pushing her protégés, and never off duty.

Close's journalism has sometimes been called "alternative," but she prefers "anthropological journalism," "diaspora media" rather than "ethnic media." The editor herself is no easier to classify, and colleagues say her views often surprise. She's pro-life, loves Rupert Murdoch's Wall Street Journal, and thinks O.J. was framed. "She's a liberal in the deepest sense," longtime colleague Richard Rodriguez says. "She doesn't want to be pigeonholed. Her loyalty is really to originality, not right or left. She's just alive to the world."

Sandy Close recognized two decades ago what many politicians, mainstream media, and pollsters were rudely awakened to in the 2012 election cycle: Ethnic communities are rapidly becoming the key drivers at the polls and in the marketplace—and hardly anyone outside those communities is talking to them, in their languages, about what they think, how they live, and what they buy. The combined reach of ethnic media organizations is more than 60 million, about one in four U.S. adults.

"She has almost single-handedly nourished, supported and kept alive all these small media projects of black and ethnic communities that are seeking truth at a local level, providing information and a voice to the poorest and most disadvantaged people in the country," says former Nieman Foundation curator Bill Kovach, who headed the selection committee.

Kovach was pleased to award the medal to a woman for the first time, which he sees as a nod to Izzy's wife, Esther, who managed the finances of I.F. Stone's Weekly. Similarly, Close and her late husband, Asia scholar Franz Schurmann, who in 1969 cofounded PNS with Orville Schell, initially to provide independent coverage of Indochina during the Vietnam War, worked closely throughout their careers.

PNS editors convened 24 ethnic-media journalists who came up with the idea of "an Associated Press of ethnic media." Koreans in Oakland wanted to know what it was like to be Hispanic in San Jose; Hispanics wanted to know what it was like to be Vietnamese in a Spanish-speaking neighborhood. "And we were frankly greedy," Close says, "to know what their content was so we could do a better job bringing our audience out of parochialism into a more cosmopolitan view of the world."

In 1995 Close won a MacArthur "genius award" and used the funding to help start two new ventures: The Beat Within, writing and art workshops for incarcerated youth, and New California Media, which went national as New America Media 10 years later.

A staff of editors fluent in various languages and cultures—Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, Hindi, Arabic, Spanish, African American—monitor the media serving those audiences, summarizing and translating stories. NAM also produces its own stories. But the old AP model of "news service" barely begins to describe NAM's vision of a national ethnic-media collaboration.

This winter, for example, NAM hosted a teleconference briefing with the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities on how the fiscal cliff and sequester cuts work for 55 ethnic-media journalists, who serve the poor communities most affected by it.

Last spring NAM arranged for a Hispanic videographer to work with a Two Rivers Tribune reporter investigating an epidemic of methamphetamine addiction among the Hoopa tribe outside Eureka. "They certainly don't want some mainstream investigative reporter to swoop in and expose it; that would only further isolate them," Close says. "There are silent spaces in America, and in these spaces people are reluctant to talk about things. If you as a journalist can help them talk about things in their community, that can be an end in itself."

In 2011, 12 ethnic media ran stories on families who'd lost their homes to foreclosure—an Indian senior engineer in Silicon Valley, a Chinese-Hispanic family fighting a fraudulent appraisal in court, an African-American "workaholic" grandmother who lost the family's home of 50 years. Over three years, California led the nation with 1.2 million foreclosures.

"They cover the economy the way nobody else does, from the bottom up," says Margaret Engel, executive director of the Alicia Patterson Journalism Foundation. "It's done with such professionalism, not just liberal bleeding-heart stories about poor. They're really writing about the scams and carnage, how insurance and banking and real estate play out in the real world."

NAM's most visible collaboration has been helping launch the Chauncey Bailey Project, an investigation into the 2007 death of one of its founders, the editor of the free weekly Oakland Post who was shot while walking to work. Over four years big daily journalists working alongside local TV, radio, and Web-based reporters uncovered evidence that led to the convictions of three men who had terrorized Oakland for years. "The project taught me the value of collaboration with other news organizations, which is all I've been doing since then," says A.C. Thompson, one of the project's leading reporters. "Building a bigger team with different skills, on multiple platforms with multiple organizations, is the way to go in this journalism economy."

Twenty-first century journalists have to "walk on two legs," Close says, both producing content and generating revenue to support it. NAM has had the most success persuading foundations to support collaborative journalism, like a recent tour for 12 ethnic journalists to learn about toxic hazards on Navajo and Hopi reservations. She spends much time fund-raising and says funders often give her better story ideas than her own.

This year Close turned 70 and is talking about succession planning. But she shows little sign of slowing down. "I wake up every morning inspired by being able to find things out," she says. "Curiosity is what got me into this. But I'm struck by how I know less, goddammit, in this glut of information than when I started."

Kimberly French is a journalist and essayist whose work has appeared in The Boston Globe, Tikkun, Utne Reader, Salon, UU World, and BrainChild.