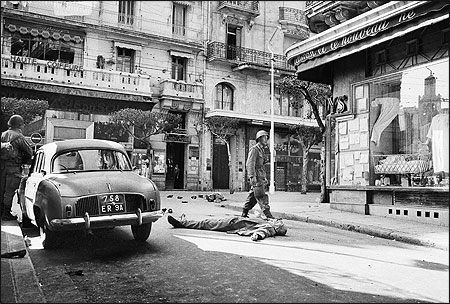

The Algerian war for independence took a deadly toll in Algiers even after France declared a ceasefire in March 1962. The city was home to the fervently anti-colonialist newspaper Alger Républicain, edited by French-Algerian journalist Henri Alleg. Photo by The Associated Press.

The dear price Algerians paid for their independence has been amply documented, but Henri Alleg's "Algerian Memoirs" is an incomparable, if imperfect, addition to that history. The French-Algerian journalist is now in his 90s and we are fortunate that his memoir, published in French in 2005, has finally been translated into English.

His book is not only a powerful reminder of the humiliations and injustices endured by a country that was colonized by France for 132 years—one that won independence just 50 years ago—but an intensely personal story. Alleg was the scion of a Jewish family of Russian and Polish origins who fled to London after the scourge of anti-Semitism and its ugly manifestations—the pogroms—spread in Eastern Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Shortly after his birth, Alleg's parents moved to Paris. There, his political coming of age was informed by the Popular Front and he developed a passion for long trips abroad; these were important for his education and his understanding of the world. After he landed in Algeria in 1939 at the age of 18, he furthered his education by enrolling in the Algerian Communist Youth before ascending to the editorship of the pro-Communist daily Alger Républicain ("Republican Algeria").

Founded in 1938 by progressives to counter the powerful press controlled by the government and landowners, Alger Républicain advocated assimilation and equal rights. In the paper's early years, Albert Camus was one of its reporters. It was not until Alleg took over that the paper became unequivocally anti-colonialist. Alleg joined the staff as a reporter in 1950 and was named editor in chief a year later. The paper never drifted from its primary mission: to be the voice of the downtrodden. Alleg's passion for this type of militant journalism almost jumps off every page devoted to Alger Républicain. Those interested in the challenge of managing a newspaper will relish the many ruses and stratagems Alleg and his colleagues employed to keep the paper alive. Alger Républicain many times was reborn from its own ashes, thanks to the dedication and ingenuity of these newspapermen.

Alleg, best known for his 1958 book "La Question," once banned in France, devotes a chapter of his memoir to this defining episode in his life. For "La Question," Alleg summoned all of his skill as a reporter to denounce the system of "enhanced interrogations" used by French authorities to quell the insurrection that had been spreading throughout Algeria since 1954. He described in minute detail the ordeal of a Communist arrested and savagely tortured: himself. The slim volume, for which Jean-Paul Sartre wrote an introduction, had a tremendous impact on public opinion as well as the French intelligentsia. It exposed the ugliness of French colonialism and the moral corruption that infects an occupying force.

It is not surprising that "La Question" was back in the news after the Abu Ghraib scandal broke in 2004, for Alleg, too, was subject to waterboarding and other means of torture. If the horrors into which the U.S. occupation of Iraq descended evoked the way the French army dealt with the Algerian struggle for independence, as described in "La Question," readers may find some resonance between "Algerian Memoirs" and current events in the Arab world. The fight against Western colonialism is a powerful theme in most of the region's countries. Anti-Western sentiment is not only the product of an ossified version of Islam or Arabism, it is also a vivid impulse in "Algerian Memoirs."

Alleg's memoir resonates with current events for another reason. In the final chapters, the author shows how the newly established Algerian state reneged on the liberation movement's promises to transcend ethnicity and religion. Algeria did not promote racist or even Islamist policies but its leaders' discourse was replete with pro-Arab and pro-Islam pronouncements marginalizing the sizable Kabyle proportion of the Algerian people, the Christians, Jews and atheists like Alleg himself. Islam was proclaimed the religion of the state. Will the inaptly named Arab Spring engender more inclusive politics or fall prey to sectarianism? See the debates about the Copts' situation in Egypt or the Shiites in Bahrain.

Alleg's fight for Algerian independence is admirable, and he paid a high price for his political engagement. Because the author's unwavering attachment to the most respectable humanistic values comes across so clearly in what he writes about Algeria, his dogmatic adherence to communism is all the more mindboggling to this reviewer. You don't have to be a rabid anti-communist to be dismayed by Alleg's fiddling with established historical facts. In fact, it wasn't until 1956—14 months after the start of the armed Algerian struggle—that the French Communist Party came around to supporting the Algerian independence movement.

Alleg presents Maurice Thorez, the leader of the French Communist Party from 1930 until his death in 1964, as a paragon of anti-colonial rule. Yet he fails to mention that Thorez, toeing the line for Moscow back in 1937, declared that Algerian independence was off the table with this statement: "The right to divorce does not mean the obligation to divorce." When Alleg many years after Joseph Stalin's death dared to criticize the Soviet Union, it was only to lament that a cult of personality dominated the Soviet tyrant's era.

Communist dogma aside, "The Algerian Memoirs" tells the story of an extraordinary life of militance, ideals and disappointments. It is a worthy read.

Aboubakr Jamai, a 2007 Nieman Fellow, has founded a number of independent publications in Morocco, most recently the online news service lakome.com. In 2003, his work was recognized by the Committee to Protect Journalists with an International Press Freedom Award.