An Occupy Oakland march in California last year took aim at the unequal distribution of wealth. Photo by Paul Sakuma/The Associated Press.

Who stole the American Dream? The short answer to the question in the title of Hedrick Smith's new book is: The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and Wal-Mart.

But the longer answer is one heck of a story, told by one of the great journalists of our time.

In his sweeping, authoritative examination of the last four decades of the American economic experience, Smith describes the long, relentless decline of the middle class—a decline that was not by accident, but by design.

He dates it back to a private memo—in effect, a political call to arms—issued to the nation's business leaders in 1971 by Lewis F. Powell, Jr., a corporate attorney soon to become a Supreme Court justice. From that point forward, Smith writes, corporate America threw off any sense of restraint or social obligation and instead unstintingly leveraged its money and political power to pursue its own interests.

The result was nothing less than a shift in gravity. Starting in the early 1970s, every major economic trend—increased productivity, globalization, tax law overhauls, and the phasing out of pensions in favor of 401(k)s—produced the same result: The benefits fell upward.

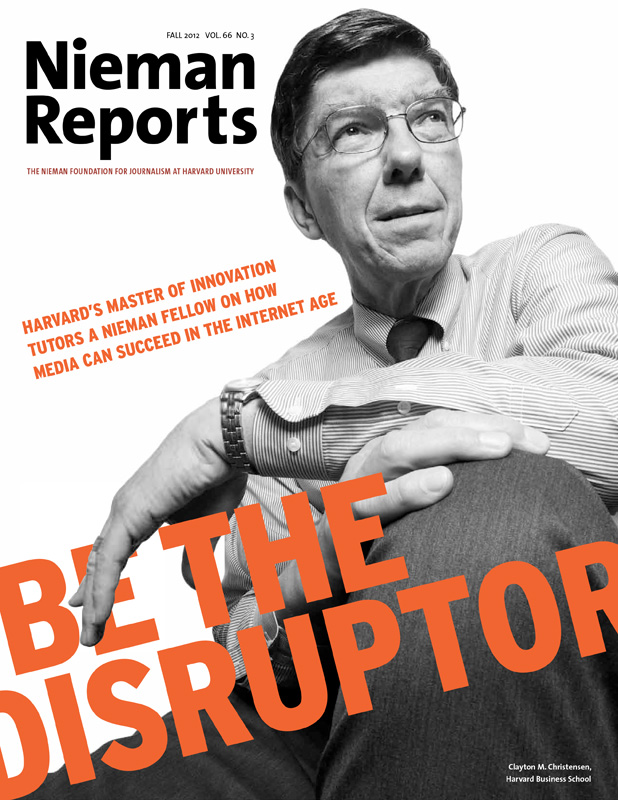

Smith, a 1970 Nieman Fellow, is at his very best as he examines, one by one, the key economic shifts of the last 40 years and shows that in each case the money flowed to the very richest Americans, particularly those on Wall Street, while impoverishing the middle class.

Nowhere was that more blatantly the case than in the housing sector. We are all well aware of how the bursting of the housing bubble has left many middle-class Americans without the nest egg they were counting on for their retirement. But Smith describes how the banks had been sucking the home equity out of the middle class for years before that.

"Instead of enabling ordinary Americans to achieve The Dream, they fashioned stratagems that stole the dream," Smith writes, describing what he calls the "New Mortgage Game." The sales pitch "was that homeowners should think of their houses not as nests … but as ATM machines," Smith writes. The goal was "perpetual hock"—and correspondingly high fees.

The banks "seduced millions of middle-class families into draining the precious equity that they had painstakingly built up in their homes" and the result was "a monumental transfer of the absolute core of middle-class wealth from homeowners to banks. Trillions of dollars in accumulated middle-class wealth were shifted from average Americans to the big banks, their CEOs, and their main stockholders."

America's Aristocracy

Again and again, Smith exposes the same relentless pull. He examines the merciless toll on the American worker of globalization, fueled in no small part by the relentless outsourcing championed by Wal-Mart, which one of Smith's sources describes as being essentially engaged in a joint venture with China.

Who benefits? Well, the Walton family, for one, which as Smith points out currently enjoys as much wealth as the bottom 40 percent of the U.S. population, or 120 million people.

The familiar story of the decline of guaranteed pensions and the rise of retirement accounts nevertheless carries a new emotional wallop in Smith's telling. Get ready for waves of retirees who run out of money long before they die not just because they didn't put enough money into their 401(k)s but because of the huge bite taken by mutual fund managers, whose fees and transaction costs average 2 percent a year.

At 5 percent a year, $1 over 40 years becomes $7.04—but at 3 percent, it only comes to $3.26. Smith quotes Jack Bogle, founder and CEO of the Vanguard Group, explaining that "you the investor put up 100 percent of the capital. You take 100 percent of the risk. And you capture about 46 percent of the return. Wall Street puts up none of the capital, takes none of the risk, and takes out 54 percent of the return."

There's so much more in the book: How bankruptcy laws have served as a means of transferring money from the middle class to the banks. How poor credit-card users have come to subsidize rich credit-card users. How stock options are "the primary vehicle for the corporate super-rich."

And there is the complete lock that the super-rich—most ably represented by the Chamber of Commerce, the Business Roundtable, and the like—seem to have on tax policy. In 2010, for instance, a majority of the public supported ending the Bush tax breaks for the top 2 percent of Americans. The argument that tax cuts were necessary to free up job-creating capital was not credible, given that corporate America was sitting on well over a trillion dollars in idle capital it just didn't want to spend. But when corporate CEOs issued a demand that all the tax cuts be extended, Senate Republicans took their side, and no one could stop them.

Smith's extraordinary clarity in describing this sometimes obscured narrative arc evidently emerges from his sense of journalistic outrage. He sees a country splitting into two, divided by a vast wealth gap. He sees the social fabric of the nation tearing. He wants to make it better.

But the hopeful chapters at the end of books like this are always jarring, and none more so than here. After showing so effectively how the rich have everything rigged in their favor, Smith nevertheless calls for average Americans to rise up and make themselves heard.

"Changing America's direction will not be easy," he writes. "It will happen only if there is a populist surge demanding it, a peaceful political revolution at the grass roots, like the mass movements of the 1960s and 1970s." He puts forth a succinct and attractive 10-point plan to fix the country that closely mirrors the typical progressive wish list. He calls on American business leaders to change their mindset and share.

He cites the Occupy movement as a positive indicator, but the fact remains that Occupy never rose to the level of mass movement, and didn't really return after winter.

Mass movements do happen, of course. Smith actually covered the ones in the '60s and '70s—along with just about every other major story of the last half-century.

But to turn things around—again, now—would seem to require leverage and power that the middle class, by Smith's own accounting, no longer possesses. Forty years ago, corporate America managed to get the money and power to flow from the bottom to the top. Now it's collected there, and congealed, and it's hard to see how to get it to flow back.

Dan Froomkin writes about watchdog journalism for Nieman Reports. He is also senior Washington correspondent for The Huffington Post.