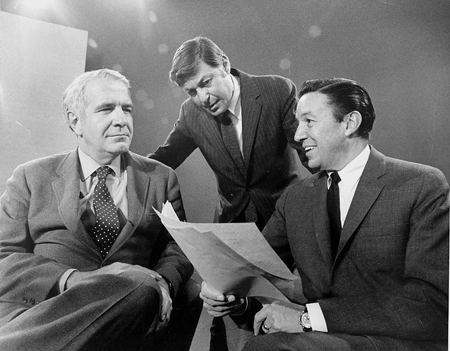

Harry Reasoner, Don Hewitt, and Mike Wallace on the set of “60 Minutes,” 1968. CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images.

Mike Wallace: A Life

By Peter Rader

St. Martin's Press. 323 pages. In his waning years, broadcast pioneer Mike Wallace declined screenwriter and filmmaker Peter Rader's request to be interviewed for his biography, "Mike Wallace: A Life." It's probably just as well. Rader meticulously researched Wallace's unique life in and out of broadcast journalism and he has crafted a narrative that is both engaging and revealing, though some readers may be put off by his admission that he wrote some "imagined dialogue." The book exposes many shortcomings and weaknesses that the great interrogator zeroed in on in others but never wanted to confront himself.

In the days and weeks immediately following Wallace's death, it was easy to watch the highlight reels of his career and feel a warm glow, but it's much harder to confront his character flaws off camera. He put his career ahead of family and friends. He could be cruel and sexist to women in the workplace. He was at times consumed with self-pity.

The retrospectives and obituaries are reminders of his unique contributions to broadcast journalism, but this biography takes Wallace away from the glowing screen and puts him on the couch. It was not easy to work with him. It was not easy to be married to him. It was not easy to be his child. It was not easy to be him.

Mike Wallace's resonant voice, his jet-black hair, his demeanor at once prickly and endearing, make him seem—in retrospect—born for broadcast. What is less well known is how Wallace learned to use his voice as a skinny Jewish kid in Brookline, Massachusetts to compensate for profound insecurity about his pockmarked face and overbearing mother. Decades later, he famously reduced Barbra Streisand to tears on camera over the very same insecurities he instinctively recognized from his own experience.

He didn't gain admission to the University of Michigan without a good word from his friendly uncle, Leo Scharfman, who was on the faculty. Wallace later left a legacy there by donating Wallace House, home of the Knight-Wallace journalism fellows. He learned the real power of his voice at the campus radio station and later at WOOD/WASH radio (twin call letters because a furniture company owned half of the station and a laundry the other half). His early days in broadcasting were less than glamorous. He once shoveled elephant dung to clear the stage for the live broadcast of WGN's "Super Circus" in Chicago.

His first marriage was to his college sweetheart, Norma Kaphan. He wasn't ready. He went off to war in a noncombat role in the South Pacific and was absent when his oldest child developed tuberculosis. Norma enlisted a family physician to prevail on the U.S. Navy to send him home. But the military was a temporary absence. Wallace's career made for a more prolonged absence in the lives of his sons, Peter and Chris. The book details how Norma's second husband, CBS executive William Leonard, encouraged Wallace to be a part of the boys' lives and welcomed his presence. It led to a renewed relationship.

Wallace's own life was profoundly altered when Peter died as a young man from a fall while hiking in Greece in 1962. The loss made him rethink his career choices. He focused more than ever on journalism. It's easy to see how his career could have continued as pitchman and game show host. But he was driven to produce more substantial and lasting work.

Wallace was married four times in all. He was not a philanderer, but this book chronicles in some detail how he seemed more comfortable with the enduring marriage to his vocation, his calling, his voice. He recognized it as a character flaw. He also did not give up on marriage, his final in 1986 was to Mary Yates, the widow of his former producer and good friend Ted Yates. Two years earlier she literally saved his life when she rescued him from an overdose of pills. Wallace later spoke frequently and freely about his own depression. He spoke less often of the failed suicide attempt. He left a note, which, Rader writes, "… befitting Mike, was rather impersonal—relating to financial matters rather than his feelings." What is glaringly apparent from the rest of this book is that had his suicide attempt been successful, Wallace would have missed the opportunity to make peace with himself and his loved ones and the world would have been cheated of more decades of tremendous reporting.

Wallace's prickly, challenging persona on "60 Minutes" meshed perfectly with public skepticism after Vietnam and Watergate and the exponential growth of television as a news medium. He spoke up for the voiceless. And that voice said, "Aw c'mon!" The phrase that Wallace chose to apply to himself may be applied to Peter Rader's fine book: "Tough, but fair."

Stuart Watson, a 2008 Nieman Fellow, is an investigative reporter at WCNC-TV in Charlotte, North Carolina.