Charles Moore's photographs shocked a nation by pricking its conscience. In the early 1960's, Life magazine carried into millions of American homes his unforgettable images of white lawmen wielding clubs over black demonstrators. His visceral and visual storytelling portrayed emotions that penetrated in ways words did not. Some credit photographs by this white son of Alabama with accelerating passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Moore, who died last year at the age of 79, had a knack for being where the action was. On the night before James Meredith became the first black to enroll in the University of Mississippi, Moore was the only photographer inside a campus building where several hundred United States marshals were trapped as whites outside fired guns and hurled bombs at them. Two people were killed and 168 marshals were injured.

RELATED ARTICLE

“Six Decades of Watching Mississippi—Starting in 1947”

- Wilson F. "Bill" Minor

It was on the streets of Birmingham in 1963 that he took his now famous picture of three blacks being blasted with high-pressure water hoses and another of police dogs, teeth bared, lunging at demonstrators. "In Birmingham when I saw the dogs I don't think anything appalled me more," Moore told The New York Times in a 1999 interview, "and I've been to Vietnam."

Life magazine published 11 pages of his photos from those tumultuous days when riots erupted in Birmingham. Moore was arrested while taking these pictures on charges of refusing to obey an officer and released with an order to appear in court the next day. Told he might face a six-month sentence, he left Alabama by plane that night and, on the advice of his lawyers, stayed out of the state until the charges were dropped a year later.

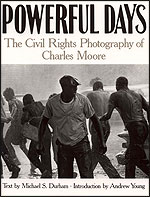

His arrest strengthened his resolve: It was the shot that mattered. "I'd let people trip me, jostle me, pull my hair and threaten to smash my camera," he said years later in an interview with The (New Orleans) Times-Picayune. As he traveled throughout the South, often with Life magazine staff writer Michael S. Durham, he encountered hostility. A hunk of concrete was thrown at Moore; another time he was beaten up. Durham wrote about this in his book "Powerful Days: The Civil Rights Photography of Charles Moore," published in 1991.

When Moore returned to Birmingham on assignment in the 1970's, it was a different city. The police chief was black and the force was integrated. "It made me feel good," he said, "that my pictures had something to do with that."

Charles Moore's historic images are online at the Steven Kasher Gallery.

Moore, who died last year at the age of 79, had a knack for being where the action was. On the night before James Meredith became the first black to enroll in the University of Mississippi, Moore was the only photographer inside a campus building where several hundred United States marshals were trapped as whites outside fired guns and hurled bombs at them. Two people were killed and 168 marshals were injured.

RELATED ARTICLE

“Six Decades of Watching Mississippi—Starting in 1947”

- Wilson F. "Bill" Minor

It was on the streets of Birmingham in 1963 that he took his now famous picture of three blacks being blasted with high-pressure water hoses and another of police dogs, teeth bared, lunging at demonstrators. "In Birmingham when I saw the dogs I don't think anything appalled me more," Moore told The New York Times in a 1999 interview, "and I've been to Vietnam."

Life magazine published 11 pages of his photos from those tumultuous days when riots erupted in Birmingham. Moore was arrested while taking these pictures on charges of refusing to obey an officer and released with an order to appear in court the next day. Told he might face a six-month sentence, he left Alabama by plane that night and, on the advice of his lawyers, stayed out of the state until the charges were dropped a year later.

His arrest strengthened his resolve: It was the shot that mattered. "I'd let people trip me, jostle me, pull my hair and threaten to smash my camera," he said years later in an interview with The (New Orleans) Times-Picayune. As he traveled throughout the South, often with Life magazine staff writer Michael S. Durham, he encountered hostility. A hunk of concrete was thrown at Moore; another time he was beaten up. Durham wrote about this in his book "Powerful Days: The Civil Rights Photography of Charles Moore," published in 1991.

When Moore returned to Birmingham on assignment in the 1970's, it was a different city. The police chief was black and the force was integrated. "It made me feel good," he said, "that my pictures had something to do with that."

Charles Moore's historic images are online at the Steven Kasher Gallery.