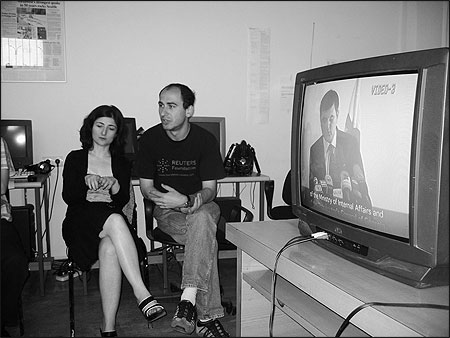

Nino Zuriashvili, left, and editor and videographer Alex Kvatashidze, Studio Monitor’s co-founders, have a difficult time finding outlets in Georgia that will broadcast their reports. Photo by Karl Idsvoog.

In Georgia, when a media organization exists, two things are likely to be true about its owner. First, it will be a business group or businessman, and second, its owner will be closely connected to those who hold government power. Since 2004 these descriptions fit perfectly the profile of the founders and owners of the controlling share of 12 out of 13 of my country's TV channels.

I was working as an investigative reporter at Rustavi 2, one of Georgia's national TV channels, when its ownership changed in 2004. Kibar Khalvashi, a businessman and good friend of Interior Minister Irakli Okruashvili, bought the channel that year. When that happened, censorship of our investigative journalism began—four of our projects were blocked.

I left my job, as did my co-worker Alex Kvatashidze, an editor and videographer with whom I collaborated on investigative projects. Along with several colleagues, we founded Studio Monitor, a production company, as a nongovernmental organization. Our independent status means there is no censorship of our stories—by us or by anyone else—nor is there any topic that we avoid covering out of fear. There are, however, topics we cannot investigate because we don't have access to the information that we need to document the story. When a TV station broadcasts our investigations, we do not allow them to drop any part of what we give them. Georgia's major TV channels—ones that are close to the government—are not permitted by the government to broadcast our stories nor do those who work at these channels attend presentations we do about our investigations.

In 2009 the Caucasus Research Resource Center conducted a media survey in Georgia. It showed that 75 percent of people expressed a desire to have an opportunity to watch investigative stories on various topics. We make our AUTHOR'S NOTE

Studio Monitor’s stories have been broadcast periodically on regional channel TV 25 in Batumi, Trialeti, Gori and Bolnisi.investigations available on our website, but the larger challenge remains finding media outlets to broadcast our stories. Since 2007 a dozen of our investigative stories have been shown at the Tbilisi Cinema House, where we also make presentations about them. They are also uploaded to other online sites and some regional TV channels show them.

Our Investigative Projects

There was one story we did after we discovered how the mayor of Tbilisi had financed 15,000 workers during a four-month period prior to the May 2008 council elections. It turns out that he diverted $7.9 million of city funds to pay for political activism. Official records showed that these funds were to be spent to check the list of people who live below the poverty line, the so-called socially vulnerable people, even though this should have been the responsibility of the national health ministry.

We obtained official documents concerning this program, and through our sources we later found out who these workers actually were—paid partisan activists—and recorded interviews with some of them. They explained how they signed agreements while sitting in the offices of the ruling National Party and how the party's district heads gave them their tasks to be carried out by Election Day, including bringing National Party voters to the polls. Essentially, the mayor's office hid this political program from public scrutiny.

RELATED LINK

Resources for Investigative ReportersAnother investigation we did involved five members of Parliament who were also members of the National Party. After they purchased designated park land on the outskirts of Tbilisi, the City Council annulled the "recreation zone" status of the park; this made it possible for these businessmen to get a permit to start construction on the site.

By changing the status of the park, the City Council committed a grave violation of the law. We reached this conclusion after analyzing documents we obtained from the City Council, Ministry of Justice, Public Registry, and Civil Service Bureau.

In another investigative piece we examined what happened to $51 million that the government allocated to assist with repairing housing for internally displaced people (IDP). Georgia has about 250,000 IDPs as a result of the wars in neighboring Abkhazia and South Ossetia. We found out that authorities worked out special terms and conditions that resulted in 20 companies being able to win these contracts—and, not surprisingly, the majority of these firms turned out to be financial contributors to the National Party.

After we obtained the financial reports and bidding documents, we checked the quality of the winning firms' work. Our report revealed breaches of the terms. Although their work was of low quality, the companies have never been officially criticized nor has any compensation been demanded from them.

In "Symbolic Gifts of the President," we investigated property that had been sold by order of President Mikheil Saakashvili. He "gave" (sold) houses that ranged in price from $11,000 to $140,00 for $600 apiece to 10 judges who sit on the Constitutional Court. This presidential decree was confidential so we could obtain the facts only after appealing to the court. By examining the judges' declarations, we could see that the houses had been stated as being their own property.

Barriers We Push Against

It is still a problem in Georgia for reporters to gain access to public information. Often we are able to see public documents only after we go through the courts. Due to actions the government has taken to block our access to public information, Studio Monitor is now involved in six administrative court cases against various public institutions; one of these cases has been sent on to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, France. Add to this legal situation the fact that databases on the websites of public institutions are very poor, and finding information becomes even more difficult.

Our financial resources are quite precarious, which adds to our difficulties, especially when one project is coming to an end while the next one is in the pre-approval stage. Our lack of facilities makes it difficult for us to implement several projects simultaneously; if we were able to work on more than one project at a time, this would make it easier for us when it comes to obtaining funding. We receive all of our funding from international donors, such as the European Union representative in Georgia, the Open Society Georgia Foundation, the British Embassy, United States Embassy, and the Eurasia Partnership Fund.

With support for our investigative work coming from donors outside of Georgia, Studio Monitor is able to remain free from internal political and commercial pressures; this means we are not answerable in any way to Georgian authorities or major business groups.

When we worked for the national TV company Rustavi 2 and we had a program dedicated to investigative journalism, our stories were seen by the largest number of people. Back then, we received death threats because of the stories we did and the danger of violence against us was always high because our stories had impact. Since we left Rustavi 2, Studio Monitor has had a hard time building a wide audience. Getting our stories seen by people remains a major challenge. Maestro TV now broadcasts our stories, but this channel is seen in only half of Tbilisi, the capital city, and in several nearby towns on cable. TV stations in a few other parts of the country broadcast them but they have limited regional audiences. Broadcasting throughout the entire country is not likely to happen, and because of this our stories are not able to influence public opinion; if they did, we would be threatened.

We are constantly looking for ways to update and perfect our professional skills through training courses. When I was covering financial topics, for example, I did a two-month training course in economics journalism at California State University, Chico. Later the U.S. Embassy financed a visit to Georgia by Karl Idsvoog, a professor at Kent State University and a trainer in investigative journalism. We also took a course in digital media in which we learned how to produce stories for different platforms—print, the Web, and mobile—and how to get our information to potential viewers, listeners and readers.

We still need training in how to better use computer-assisted reporting and how to work on cross-border investigative projects. Romanian journalist Paul Radu, co-founder of the Romanian Center for Investigative Journalism, recently came to Tbilisi and we discussed possibilities for collaborating with him. Crime and corruption do not recognize state borders. If our investigative efforts remain focused only in Georgia and we cannot actively talk with and share information with reporters in other countries, then we will no longer succeed in our mission of uncovering corruption and bringing our investigative stories about it to public attention.

Nino Zuriashvili is the co-founder of Studio Monitor, an independent production company in Tbilisi, Georgia.