In releasing its study on how the press handled the most recent Clinton crisis, the Committee of Concerned journalists said its findings raise “basic charges about the standards of American journalism and whether the press is in the business of reporting facts or something else.”

It is the “something else,” yet unnamed, that is of deep concern to many. The explosion of unsourced or poorly sourced stories, opinion pieces, judgmental speculation and dire predictions exceeded any prior incident in the long saga of “feeding frenzy,” as coined by University of Virginia Professor Larry J. Sabato. Perhaps the “something else” may be more narrowly defined as first drawing conclusions, then chasing the facts to support them, a sharp departure from the traditional practice of finding the facts before making a judgment.

“Looked at another way,” the study said, “the picture that emerges is of a news culture that is increasingly involved with disseminating information rather than gathering it” because of excessive use of stories originated by other news organizations, much of it unverified.

Unfortunately, newspaper editors and broadcast news directors lacked the courage to use the power they have—to insist that reporters adhere strictly to the old-fashioned rules for closing the gate on poorly sourced stories. Instead, they bowed to the false argument that since the rumors were in the public domain—even if put there by unprincipled outlets—they were therefore legitimate news. If events show that Clinton indeed was guilty of some of the charges, the fact remains that the media ran ahead of the evidence.

The study, conducted for the committee by Princeton Survey Research Associates, comprised a detailed examination of 1,565 statements and allegations contained in the reporting by major television programs, newspapers and magazines over the first six days of the crisis beginning january 2 1.

“From the earliest moments of the Clinton crisis, the press routinely intermingled reporting with opinion and speculation—even on the front page,” the committee statement said. “A large percentage of the reportage had no sourcing,” and the usual rule of having two sources for anonymous reports was widely abused.

All this left too complicated and incomplete a maze for the public to follow, even for some of us trained in the devious ways of Washington journalism and politics. What many perceived in the rush for opinion ahead of facts was an unconvincing mass shout of “GOTCHA!”

Perhaps the greatest failure—particularly for the mainline news organizations-in this exceedingly difficult assignment lay in identifying the sources of the stories. While some reports gave no source whatever others said “according to sources” (which says nothing whatever), “sources close to the investigation,” “sources who listened to portions of the tapes,” or “lawyers who listened to the tapes” and so on.

None of this came close to providing balanced coverage in the quagmire that quickly developed around the grand jury sworn to secrecy. So the sophisticated reader probably figured that “sources close to the investigation” were in the office of the special prosecutor, in which case all of the charges conveyed were one-sided and probably distorted. Likewise “sources who listened to portions of the tapes” were most certainly in league with the prosecutors and those portions of the tapes surreptitiously recorded by Linda Tripp were highly selective. Nor did “lawyers who listened to the tapes” carry much authority in a situation where there is a lawyer of every kind and stripe under every bush anxious to put a partisan spin on every story. But rarely ever, according to my own limited research, was a flag raised to alert the reader to the inadequacy of the information at hand.

Once given birth, the story based on unnamed sources often took on a life of its own, circulated and repeated by various outlets with no sourcing other than the news organization that originated it, if that. It became almost impossible to stamp out the circulation of such stories and separate them from plain rumors. Even the more responsible call-in shows were drawn into the business of perpetuating unfounded reports. A caller would go on the air and blurt out some questionable assertion picked up from the rumor mill, with neither the guests nor the host of the show able to set the record straight. Of course, this happens all the time on call-in shows, but in the latest Clinton crisis it exceeded all previous bounds of irresponsibility.

Before further discussion of this issue it may be helpful to look at how we got into a situation in which the credibility of the press has been so seriously challenged. Involved is the confluence, currently occurring, of three historic changes in the latter part of the 20th Century:

- The first is the law that authorizes the appointment of special prosecutors with a virtual unlimited hunting license to investigate allegations of illegality by government officials. This law is being seriously challenged, partly because of charges by President Clinton’s supporters and others that the present investigation has been politicized to favor the president’s enemies.

- The second is the law that permits sexual harassment suits in the federal courts and gives lawyers the right to rummage through the sexual lives of a range of persons involved in the civil suits.

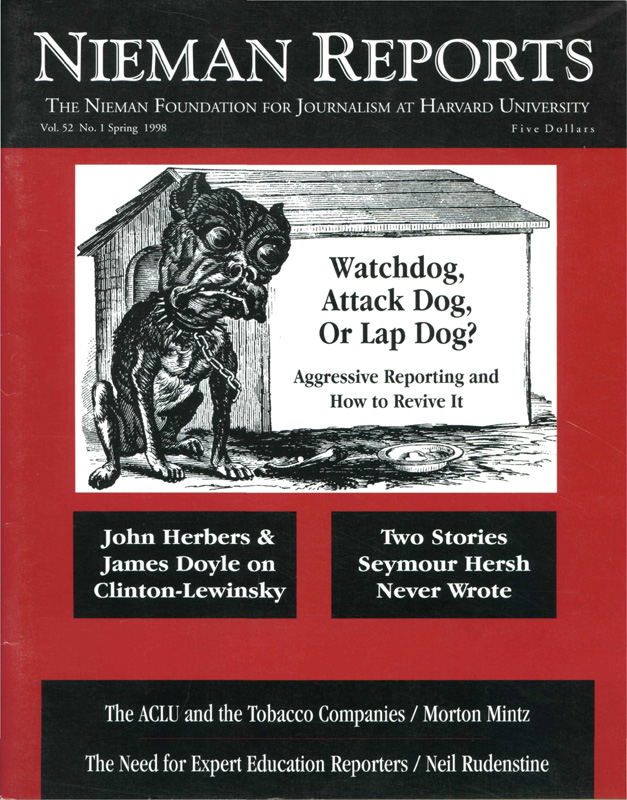

- The third, and of major importance here, is the changing role of the press in disclosing defamatory information about public officials. It is easy to forget that in most of this century the press, protected by the First Amendment, served in varying degrees as an unofficial watchdog of the public interest. It was left to the political parties to screen candidates for public office as to their character and electability. The press’s watchdog role was primarily in the realm of government, not the electoral process.

When the political parties began to decline and candidates could win office without party support the press moved in to fill the vacuum. The Watergate scandal of the early 1970’s elevated the importance of character in public officials. The watchdog became the attack dog, with news organizations sending out reporters to search for wrongdoing. Candidates and officials were held to higher standards than the society in general, even as the population became more permissive of private behavior.

Reporting based on exposing wrongdoing developed a culture of its own. When I was Assistant National Editor of The New York Times in the mid-70’s, a top reporter instructed me on how the system works. The initial attack should be followed by more stories, daily and on page one if possible. This included holding out information for another story if needed to keep up the drum beat. The kill is important. As Clinton became an elusive prey in the 1992 campaigns there were repeated predictions in political-campaign circles that he was about to be brought down. When he was not the attacks continued into and through his term in office, with the help of the special prosecutor and the ideological right wing, which had its own agenda. This is understandable, and perhaps the attack dogs were right. But it helps explain, at least in part, the excesses of the recent coverage and the impression of “GOTCHA!” that made a more detached public skeptical of what it was being told.

At the same time there was an explosion of new television and radio outlets, talk shows and web sites, many with tabloid formats. The traditional A.M.-P.M. news cycles gave way to a new cycle every minute of each 24 hours. The mainline press got caught up in following stories of sex and violence dug up by the tabloids and rumor mills. All of this helped lead to a cheapening of public dialogue. The New Yorker, once an eminent literary magazine seeped in restraint, recently published a cover showing a bevy of microphones all pointing to Clinton’s genitals, a drawing mild by comparison to the flood of cartoons and jokes in the public domain.

The mainline press rightly seized on the story as a possible threat to Clinton’s presidency, but the sex angle soon took over as the prominent sector of coverage. And it dominated the armies of journalists in Washington. In a forum at American University three weeks after the Lewinsky story broke, a man in the audience asked a panel of prominent journalists how a public interest agent could persuade their bureaus to consider reporting substantive developments in the environment, health or transportation, for example, when he could not even get through on the telephone. The answer was quick and unanimous: forget it.

One lesson from all of this is that the mainline press should tighten up on its sourcing. Reporters and editors insist that they cannot give up unanimous sources altogether without forfeiting information the public should know. Since the various news organizations are incapable of working in concert to improve their practices, this is probably true. But over the years of “feeding frenzy” it became routine to use vague phrases such as “according to sources close to etc.” without any explanation that the information being conveyed could be distorted.

The two-source rule can be useful in many cases to assure a degree of accuracy, but in the quagmire of the Lewinsky case it is less so. Too many lawyers, too much lying and distortions, too many animosities. It would be refreshing to hear of a reporter courageous enough to tell a source, “I want your leak, but I have got to give readers (listeners) some guidance as to what your interests are.” If that doesn’t work, there should be a paragraph high up in the story pointing out that this is the best we can do but there may be another side of the story. As proof of how fragile leaked information can be in the Lewinsky case, there have been stories quoting lawyers or others by name publicly disagreeing as to the facts. Such a story might well have been leaked only as an anonymous source, leaving a distortion no responsible editor would want to claim.

The news organization might also want to consider whether it is wise to continue to hold public officials to higher standards in sexual conduct and other personal behavior than the society in general, in view of the fact that the double standard results, as some believe, in worse, not better government. Some of the leading examples of excess in “feeding frenzy” have fallen under this category: for example, Jimmy Carter’s “lust in the heart,” Gary Hart’s extramarital love life, Barney Frank’s homosexuality, among others. There is some concern, too, as to whether it is wise to continue to allow prosecutors to entrap public officials by enticing them into crime and to treat public officials like the Mafia by giving immunity to small-fry suspects in order to land the big fish, possibly encouraging false testimony and encouraging talented people to shy away from politics.

These are some of the things that have led to controversy run amuck. There was talk among journalists as the Lewinsky story broke about competition for sources. Newsweek was taking kudos for being first and some editors were complaining that their staffs did not have an inkling of what was about to break. In view of the findings by the Committee of Concerned journalists, it would seem the worry should be about Whether the mainline press is becoming too much like the tabloids or “something else.”  John Herbers, Nieman Fellow 1961, covered the White House for The New York Times during the Watergate scandal, was Assistant National Editor and was Deputy Bureau Chief in Washington and, before his retirement, was the paper's national correspondent based in Washington.

John Herbers, Nieman Fellow 1961, covered the White House for The New York Times during the Watergate scandal, was Assistant National Editor and was Deputy Bureau Chief in Washington and, before his retirement, was the paper's national correspondent based in Washington.