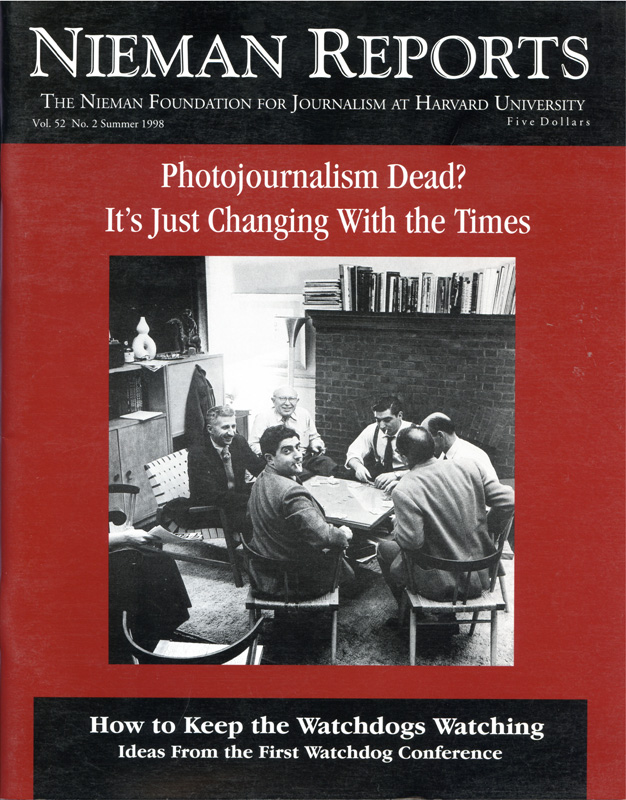

The simplest outing can turn into a nightmare for Alice Williams. Her son Joey’s fantasy life takes over as he demands a haircut like that of the Statue of Liberty. His mother tries to refocus his thoughts, but Joey becomes confused and angered.

When I first met Joey and his mother, there was not a place for the 10-year-old boy to get the help he needed.

In the early 1990’s, close to 200,000 children and teens in Tennessee were in need of treatment for mental, emotional or behavioral problems. Families without financial resources were having to give up custody of their children in order for them to receive treatment. And some children were separated from their parents and community to be sent out of state for their care.

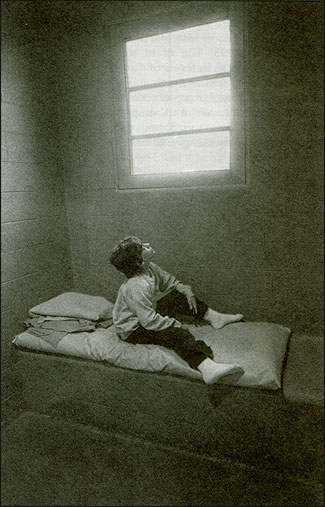

All too often the solution was a locked institution. Tennessee was more likely to place a child in a psychiatric hospital than were similar children in 48 other states.

Hospitals and juvenile detention centers were the only answers for the children I met such as Joey, who inhabited a fantasy world of his own creation; or like Chris, a 13-year-old chronic runaway who often ended up behind detention center bars.

Three reporters joined me in telling this story. Up until then, the sensitive cloak of anonymity had protected families dealing with mental illness. Through patience, we gained the trust of parents and concentrated on the personal stories of children and families in crisis—stories that until then had been mostly overlooked in our state.

The families whose stories we chronicled were desperately trying to hold their lives together while navigating their way through Tennessee’s bureaucratic maze.

The story’s impact was in the combination of words and pictures. Neither could have stood alone to make such an impact. It was a collaboration that ultimately allowed our readers to empathize, and then demand a change in our flawed system.

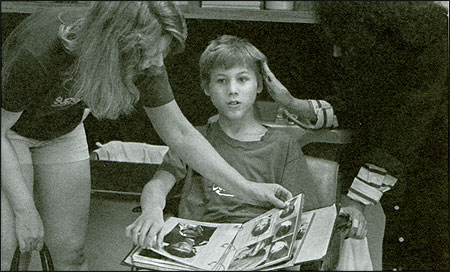

Joey leaps from his barber’s chair and tries to run into the street.

Alice has been taught how to use a double hammerlock, placing Joey’s face to the ground.

Alice is afraid Joey will become dangerous when he gets older. Some time later, because Joey cannot be adequately cared for in Tennessee, he is sent to a residential treatment center in Florida.

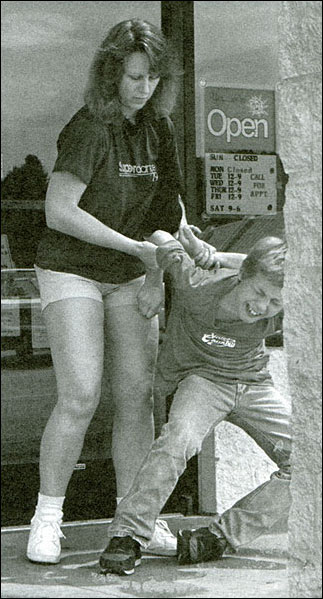

“He’s not what you’d call a bad kid. We just can’t control him,” Bill Young says of his son, Chris, 13. Chris’s parents lament they don’t have the money or the insurance to pay for the counseling Chris needs. Out of desperation, Bill Young turns Chris over to the custody of the state’s Department of Human Services.

Ashley Fiedler receives support after controlling her temper tantrum. This state-funded therapeutic center is one of the few in Tennessee that deals with behavioral disorders of young children.

Chris Young awaits deposition of charges against him for running away from home. He will receive little, if any, mental health evaluations to determine the cause of his problems before he is placed in foster care.

Nancy Rhoda is Special Projects Picture Editor for The Tennessean. She was a Nieman Fellow in 1980.