Melissa Ludtke: You’ve spent nearly two decades of your life documenting domestic violence and focusing to a great extent on the impact it has on children. Why do you think this is such an important story to tell?

Donna Ferrato: I see the children as the ones who suffer repercussions more strongly than the women do. In my experience, women who’ve been abused by their husbands, if they can get away from him, get into a shelter, and start going to support groups, they heal. They are able to make sense out of what happened and go on with their lives. But the children I usually come in contact with, they are like time bombs. In a therapy session, I saw a young boy climb the wall, scale it like a human fly when forced to remember what his father had done to his mother again and again and again.

ML: What aspects of this story do you think you, by using your photographer’s eye, can tell that perhaps writers have a harder time conveying?

Ferrato: I think that a photograph of a face that’s been through a lot, a face with emotion, tells more than pages of words. The photograph makes people identify with and often feel something for the person because they can see that person is real. We never can quite tell if the story is real when it’s an essay without photographs. The photos give it a reality. And certainly a black and white photograph pulls us deeper in than a color photograph does. Color is often distracting. We get so easily distracted by the detail of the wallpaper or the pattern of a woman’s dress.

ML: One of the things that clearly has to happen when a photograph of a face is used to portray a situation or to bring an issue to life is that the privacy of that child’s life is broken. Recently I heard Dr. Maggie Heagarty, who is Chief of Pediatrics at Harlem Hospital, tell a group of children’s journalists that those who use poor and sick children’s real names and publish pictures of their faces should “fry in hell.” She was very angry at certain members of the media who had displayed photos of so-called “crack” babies across the front pages of their publications. How do you reconcile this issue of privacy in these children’s lives with turning their faces into published images?

Ferrato: Perhaps I’m one of them who will fry in hell because I have done something like that, most recently with Ernie’s story, then again during this past summer with a story that appeared in The New York Times magazine about child sexual assault in South Africa. In The New York Times story, there was a nine-year-old girl named Masindy who had been raped by a neighbor…. Her mother gave me permission to follow them through the medical examination, treatment and court proceedings.

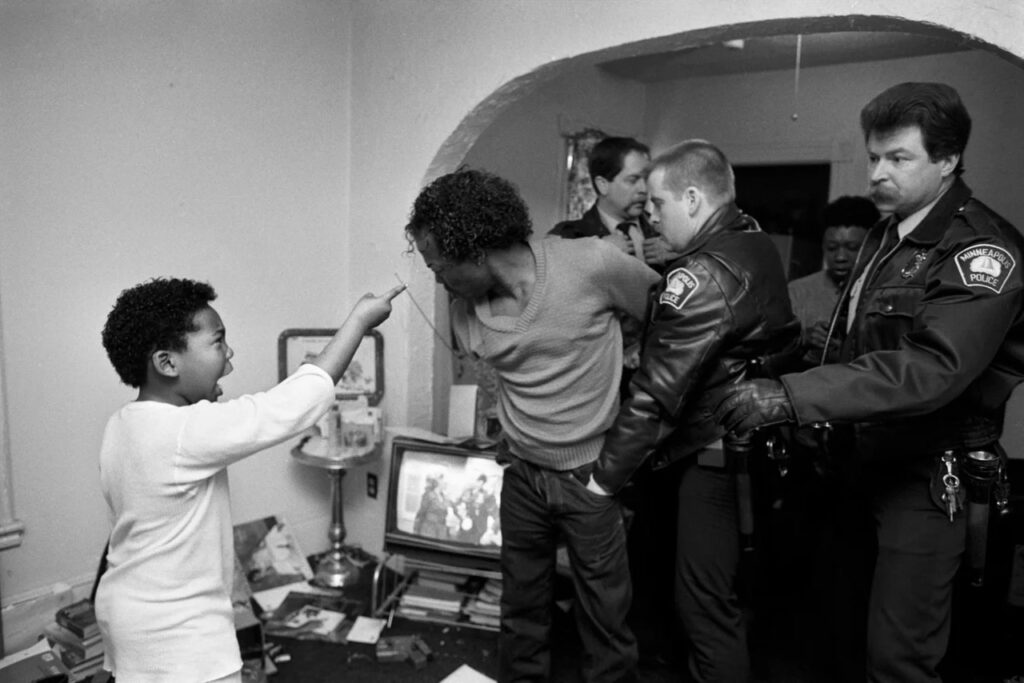

“The boy is saying to his father, ‘I hate you for hitting my mother, and I hope you never come back to this house.’ Nobody, even the parents who signed a release for this picture, realized how powerful it was going to be until they saw it in the magazine and they flipped out.” —Donna Ferrato.

Photo © Donna Ferrato, Domestic Abuse Awareness Inc. (NYC) from the book “Living with the Enemy” (Aperture).

ML: You mean you followed her with your camera?

Ferrato: With the camera, I told her story. I was really the only one there. Sometimes her mother couldn’t even be there because she was so poor she had to work and then be at home with her other children. I was able to spend that time with her at the hospital and stayed with her while she was diagnosed with syphilis. I didn’t think that it was right to use her real name in the story [the editors did decide to use it], but I firmly believed people needed to see her face, to understand that this is a real child. I hope that children are not exploited by my work, but that through it they have a chance to show what they are going through. They have a right to be able to show that and to say, “I hurt, I’m angry, this has happened to me. I need help.” Like Ernie through his behavior of trying to hurt his sister was saying, “I need help, I am in a rage.” I believe that photographs can point to that rage far better than any words connected to an anonymous child.

ML: Do you always get permission from the guardian or parent to publish photos of a child?

Ferrato: Always. Not just the guardian or parents. I talk with teachers. I talk with doctors. I talk with everybody connected to the child.

ML: Do you also talk with the children about the fact that their images will be used?

Ferrato: Yes. With Ernie, who was seven-years-old, I spoke to him all the way through it. He knew what was happening, as much as he could. When the story was ready for publication, I drove from New York City to Vermont to talk with Ernie, to show him the story, to explain to him what this was about, and why it was important for people to see this. And I said, “You’re getting help now, Ernie. Your life is changing. And people understand how angry you were and how scared you were inside. You still need a lot more help. But there are other little kids who aren’t getting the help and who have the same fears and are terrified of violence and they act it out and they’re not getting help. And maybe you can help other kids, so that there will be programs set up in their communities.” That is how I explained it to him. Maybe it is too much to put on a child. But today there are so many bad things that happen to children, they don’t have a chance to be innocent anymore.

ML: In another conversation you mentioned the reluctance some editors have to publish images like the ones you photograph. Why you think this is so, or what’s been conveyed to you by these editors in terms of what causes this reluctance?

Ferrato: Perhaps it is to do with protecting the rights of the child. Perhaps the child isn’t really old enough at nine or 10 to say whether or not they want their story to be put out in the public’s eye. I will give them that. But at the same time I think that what’s been going on for the last 10 years is the dumbing down of America. There is a great reluctance on the part of editors to tell stories which are too tough or too strong and show the realities of people’s lives. And when you get into children’s lives, editors are extremely squeamish. But they’re not afraid to show the children after they’ve done some horrible deeds, after they’ve killed five kids in the schoolyard. Then they’ll show that picture on the cover of every newspaper in the country and on TV every night. For whatever reasons, the editors at Life and The New York Times were afraid to use the pictures of Ernie. What the top people at The New York Times said was that they felt that it would ruin this boy’s life. I just didn’t agree. And I really felt, also, that this boy had the potential to help countless other kids and to make people understand these children need help….

Ernie’s story is a positive story. It shows him in trouble. We did not go in there and do a quick hit and get some pictures of him freaking out and attacking his sister. We stayed with his family, off and on, for more than a year. We did an extensive interview with his father in prison, who had been abusive with Ernie and extremely violent with the mother. We got him to understand that his children are the real victims and that he’s responsible for his son being so angry and beating on his sister all the time and beating on kids in the playground. The father is responsible. The father has to change his behavior. The father has to show his son the right way to be a man…

For so long we didn’t see the faces of these kids and so the men who did these kinds of things were able to hide. The kids were anonymous before. By showing their faces, these children gather their own kind of strength and power from being heard and being understood about what happened to them….

Especially with children, a journalist has to follow through and figure out how to protect them. It is a big step for the children’s mother or father to say “Yes, we believe that this story should be made public.” But then how do we protect the children in their communities? I did not want for Ernie’s mother to have this story shown all around their hometown. In the end, it was good that it wasn’t published in Life because that would have meant it would have been at the checkout counter of her local supermarkets. It was better that it appeared in Mother Jones where it would not be put next to all of those magazines that sensationalize everything. The idea of Ernie’s story is to educate people, including children, about what was happening in so many families.

ML: So from your perspective, using these children’s images has to be done carefully and it has to be done strategically?

Ferrato: Yes, in a way that makes people care about what is happening. I don’t think it sinks into their minds for very long if they can’t see it.

Donna Ferrato is a photographer whose documentation of domestic violence has earned her numerous journalism awards. In 1991, Aperture published “Living with the Enemy.”