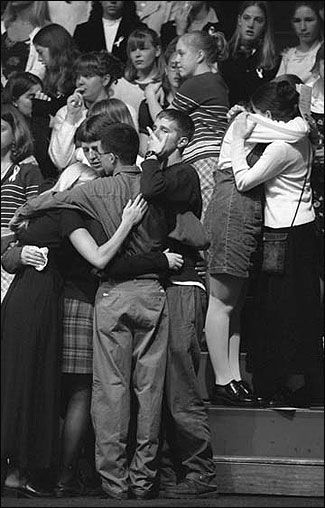

Students show their grief as the procession of slain teacher John Gillette leaves the McComb Field House on the campus of Edinboro University where an open memorial service was held. Photo by Rich Forsgren/The Erie Times-News.

It began with one of the hundreds of calls we hear each day over the police scanner, most of them routine, most forgettable.

It came in on Friday night, April 24, 1998. Details were sketchy at first: there’d been a shooting at a school dance in Edinboro, Pennsylvania; a person was running from the scene. Later we would learn that a middle school teacher was dead, others wounded, and a student from the school accused of the shooting.

For the next week, our reporters and editors—who write for three papers, The Morning News, The Erie Daily Times, The Sunday Times-News—would find themselves covering this story. All of us understood after the first wave of reporting that this was an event that would capture the attention of national media because of its similarities to other recent school shootings. Our hunch soon proved true. Print and electronic media from outside the area soon arrived in force.

Their presence, while intrusive for many, forced our reporters to relearn an essential lesson. As local newspapers, we remain members of the community forever. We live among those we write about and photograph long after other reporters leave. Mistakes and insensitivity made early on in a newspaper’s coverage can later return to sour relationships with people who, through no fault of their own, find themselves pushed into the less empathetic glare of the national press. Our professional pride urged us not to let outside media produce better reports than ours. But we cautioned ourselves to try, within the dictates of our job, to follow the wishes of the victim’s family and the community during the week. Maintaining that perspective turned out to help us a lot as the story evolved.

On that first evening, our police reporter called the story from the hall where the dance was held. Our photographer was able to get us a picture of shocked students and parents for Saturday’s page-one story.

The next day we sent two other reporters and a photographer to Edinboro while a host of others worked the story from the newsroom. Our reporters in Edinboro were both experienced journalists and had covered police stories before, though neither had specific expertise in juvenile violence. Our overriding concern was straight-forward newsgathering: Who was the student? Who was the teacher? Was there any connection between them? Why did the student fire the gun? How did the community react?

Even at this early stage, our reporters discovered that the adults in the community had closed ranks. One reporter and the photographer drove to the teacher’s neighborhood. Instead of going immediately to the family’s home, they talked to neighbors first, including one acting as family spokesman. He told them the family preferred to grieve privately and that meant no interviews. We respected their wishes and avoided calling the widow or the teacher’s grown children. Our reporters did speak with several students who were at the dance and who knew the student accused of the shooting. Most spoke freely. In one case, a mother told one of our reporters not to talk with her son or others in their circle of friends. The reporter complied.

By Saturday afternoon, many members of the national media had arrived. Their ever-increasing numbers further complicated newsgathering, making original reporting all but impossible to do. By then, school officials had set up a centralized media center.

One of our strengths, we discovered, emerged out of how we wrote about this story when it first broke. The Sunday paper, The Times-News, circulates widely in Erie County. Even though overall numbers have dropped recently, we still enjoy one of the highest market penetrations in the country.

As part of Sunday’s coverage, our sports editor wrote a column about the teacher, who for many years coached at area high schools. His family called the sports editor to thank him for the tribute and to compliment the paper’s efforts. Later, the editor broached the topic of reporting about the funeral and helped arrange for coverage of it. The family allowed us to cover the funeral based in part on how we conducted ourselves as reporters and how the paper read that Sunday.

As more time passed, many Edinboro residents grew exasperated with most reporters and photographers. They were unaccustomed to granting interviews. The rush of news media was disconcerting. It made them feel uncomfortable. We knew we had to be respectful of family members if we wanted to maintain our access and provide comprehensive coverage.

This balancing act was played out on the day of the funeral. Our photographer was the pool photographer for all print media. He had to arrange coverage with the funeral director and the victim’s family. We learned that the family wanted to have the funeral photographed but did not want the photographer to be obtrusive. Having this awareness made us able to comply with that request and still come away with powerful images.

In the midst of planning our funeral coverage, these sensibilities were tested. The family asked that news media stay out of the cemetery. We could be on the road leading up to the gravesite, but the family wanted a private burial with friends and members of the Edinboro community. We knew, however, that even with these restrictions, the crowd at the cemetery was going to swell to perhaps 2,000. We discussed renting a plane and photographing the scene from overhead.

Technically, one side of the newsroom argument went, we wouldn’t be in the cemetery. We’d be following the family’s wishes and still be able to run an amazing news photo. In a meeting of top editors, the idea of an overhead shot was rejected. We decided that failed to meet the spirit of the family’s request. We used photographs from the road and elsewhere that complied with their wishes.

Later that week, after the funeral, our photographer who worked on the funeral procedures with the teacher’s wife also arranged an interview. One of our lead reporters was writing a story piecing together the events of that Friday. Using information known only by the teacher’s widow, he was able to weave what both the teacher and student did until the time when the shooting occurred. We were able to get this information because of the way we’d handled the reporting and photography in previous stories on this tragedy.

Since then, staff members have written several related stories. Our earliest efforts focused on news events, among them the trend in many schools to install metal detectors at spring proms. We interviewed national experts about how the shooting would affect the community. They told us that our community was forever changed, that we would make decisions and base policy on preventing another shooting.

We also followed the court proceedings of the student accused in the shooting. He has yet to face trial. But coverage of the preliminary hearings broadened into a series of stories on the juvenile justice system. As part of the stories, we looked at the history of the system, which turns 100 next year. We also examined specific cases of juveniles who have succeeded and failed. It is doubtful these kinds of stories would have been pursued and given the prominence and length they were unless we’d been touched by this violence. We plan to publish more stories related to this central topic of juveniles and violence.

The lesson from Edinboro, as the story is called in our newsroom, is that sometimes it’s better to try to think beyond the initial rush of reporting.

That’s not always possible, or prudent. Yet our experience tells us that it is important to do so, especially when reporters have to return later to face family and community members. Doing so, we were still able to offer our readers a credible report. And we learned that our conduct as journalists helped us in our overall reporting as we gained the trust of potential sources. Those well treated during the time of crisis were certainly more receptive to us as their grieving began to ease.

Bob Lloyd is Executive Editor of The Morning News/Erie Daily Times in Erie, Pennsylvania.