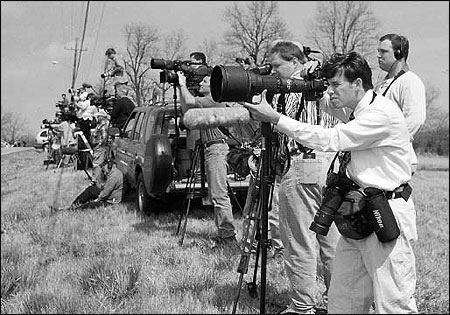

Photographers line airport road to photograph one of the funerals of a Westside Middle School shooting victim. Nettleton cemetery is located across the street. Photo by Bill Templeton/The Jonesboro Sun.

It was awful. We were all staking out the Craighead County Jail outside of little Jonesboro, Arkansas one afternoon last March. Inside were two boys who the day before had shot 15 of their classmates and teachers in a midday ambush at Westside Middle School, killing five. Now the pack of us, probably 100 print and television journalists from around the world, was waiting for people to show up for the boys’ arraignment. We surged toward each car that pulled up, and when one boy’s family finally emerged from a car, the mob surrounded them hungrily. The miserable clot of family members hugged each other for strength and support as they silently made their way along the 50-foot walk to the building, the journalists moving with them like a human oil slick, silent, too, except for one British journalist who called out, “Have you spoken with the boy? Has he expressed remorse?” His accent drew the final word out to sound like “remauwss.” Again, “Was there remauwss?”

I had no idea whether the boys felt remorse, but I sure did. These people of Jonesboro were made victims twice: first by the boys and then by us. Many of those thoughts were confirmed more than a month later when the Arlington, Virginia-based Freedom Forum co-sponsored a public meeting in Jonesboro with the local newspaper and Arkansas State University. Though some praised the journalists for hard work and compassion under pressure, the general sense was that those of us who had arrived to tell the story had only contributed to the town’s nightmare.

Retired Lt. Col. David Grossman of Jonesboro said that many he talked to spoke of “enormous anger” over the journalistic swarm. “The analogy that was made was one of flies on open wounds,” Grossman said.

Not a pretty comparison. But what the news media did in Jonesboro wasn’t very pretty.

The hat I usually wear at The Washington Post is that of a science writer; my reporting assignments usually involve coverage of the Food and Drug Administration, the Internet and other science and technology topics. When the boys in Jonesboro opened fire, though, the regional bureau correspondents who would usually be sent were unreachable. I offered to go and ran for the plane with the clothes I was wearing and a borrowed laptop and cell phone.

In pulling together enough interviews to round out the first-day story, I rang up $300 worth of phone calls on the plane to Memphis and wore out a cell phone battery on the drive to Jonesboro that night. Experts in adolescent psychology I had spoken to for stories on behavioral science told me that violence in schools was on the rise, though by most measures it was actually falling. Once I arrived that night, Jonesboro locals gave me what information they could.

I was proud of the stories I wrote that night and over the next few days, although of course they could certainly have been better—sharper, more focused, smarter. But I was dismayed to see a lot of the other news reports that came out of Jonesboro. Many relied for many of their quotes and observations on “activists” who each took the tragedy as an opportunity to rehash their attacks on violent television and movies, or on the lack of religion in the schools, or whatever societal ill they were most involved in rectifying. Others looked to causes in dark undercurrents of violence and gun ownership in southern culture.

As a science reporter, I was stunned by what I was reading and seeing about this story I was now covering. The most basic rules of epidemiology said that anything held up as a cause of a condition or a disease should include the afflicted and exclude the well. The Jonesboro story presented the opposite case. Kids across the nation see the same TV shows and movies. Guns were everywhere in Jonesboro, where the beginning of hunting season is a school holiday. Where was the distinction that could account for these two boys’ actions but which would explain why Jonesboro and a thousand other towns hadn’t erupted into bloody violence? And if there was something inherently southern about the crime, how do we account for Mitchell Johnson’s upbringing in Minnesota? It didn’t make sense.

In fact, the powerful hold of incidents like the Jonesboro shootings on the national psyche is not that they are typical but that they are unique. As I watched and read the stories about the “southern gun culture,” I recalled that I learned to shoot a gun when I was growing up not too far away in Texas, and I fondly remembered hunting trips with my folks. But I was no killer, and neither are millions of other kids in the South who learn how to shoot when they are young.

I was so troubled by the trip and the stories that came out of it that I wrote an essay for The Post’s Outlook section. The headline read “Pat Journalism: When We Pre-Package the News, We Miss the Story.” In it I wrote, “What bothered many of the town’s citizens—and still tears at me weeks later—was the way that many journalists looking for quick answers out of Jonesboro seemed to have brought them along in their luggage.”

I was prepared to be treated like a self-righteous prig by my colleagues, but their response was overwhelmingly positive. After the story appeared in Outlook, I received far more phone calls and letters than usual, all of them congratulatory. A Supreme Court reporter for a competing newspaper said that I had expressed his feelings exactly, and a network television producer thanked me for saying what “needed to be said,” even if the piece came down the hardest on her colleagues in television.

The piece ended with this: “I’m not saying that we should ignore stories like what happened in Jonesboro. I’m simply saying that as journalists, we should cover these stories more thoughtfully, and with decency and compassion, instead of cookie-cutter bathos. We should, in other words, do what we’re paid to do: get the story right.”

It sounded great, that last line. I’m still trying to figure out what it means. I do think that it means taking every story on its own terms: what makes one particular incident different from others is just as important as what makes it the same. It also means paying attention to more than just the accuracy of a story, our gold standard: it means getting the tone right as well. It’s only natural to try to play a story for all it’s worth, to try to imbue it with all of the emotion we think it can support. But sometimes we ring an alarm when a calmer message would do. Sometimes, I guess, you have to dare to be dull.

John Schwartz is a science writer on the National Desk of The Washington Post. He has written about the Food and Drug Administration, the tobacco wars, dinosaurs, the Unabomber and Viagra. He writes a regular column on social implications of computers and on-line technologies.