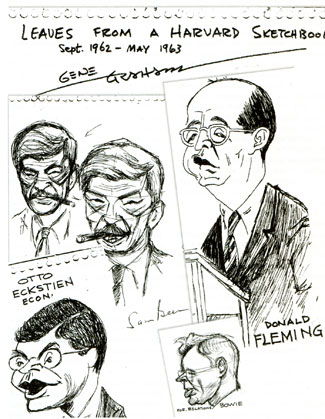

Pages from Gene Graham’s Nieman year sketchbook.

Confession: I actually went to journalism school. And now I teach in one. But I’ve also spent plenty of time in newsrooms, a dual perspective critical to good journalism education.

When I first switched from a San Francisco newsroom to a Boston University classroom to teach basic reporting in 1981, I viewed it as temporary. I was resettling in the East with my husband, who’d earned his doctorate from Harvard the same year I was a Nieman Fellow (1979), and our newborn daughter. Now that child is a senior in high school and I’m still teaching at B.U. Whew. Perhaps it’s time to reflect: Is this an honorable calling? Is journalism education necessary? How did I develop my journalistic values, and how do I pass them on?

I’m now Co-Director of B.U.’s On-Line and Print Journalism Program. That title alone conveys key technology changes from when I was an undergraduate at the University of Illinois, taught by men in suits pacing up and down clanging rows of typewriters. Yet those professors emulating gruff city editors were doing what I still consider crucial in educating future journalists: making classrooms as much like newsrooms as possible. The conundrum for schools of journalism is hiring professors who can build on real-life careers and keep current, neither falling into the “war story” trap nor having no stories at all to tell.

In 1996, I returned to a city room as part of a program designed by the American Society of Newspaper Editors to reacquaint (or, in some cases, acquaint) professors with today’s journalism. The Anchorage Daily News called me an “intern,” so I was immediately time-warped to a student mindset. But I was an intern with chronic déjà vu. I’d been told by grizzled veterans nationwide, people my age who’d stayed in the trenches, that newsrooms had changed a lot and that the business wasn’t as much fun as it used to be. I thought it was fun to be a reporter again, finding myself in new places, meeting new people, learning new things. These were all reasons I loved journalism in the first place.

What did surprise me was that newsrooms literally still looked almost the same as they had 15 years earlier when I had my last full-time job in one.

Men were mostly in charge and there were far fewer minorities working in them than at my last permanent news post, The San Francisco Examiner. I was less surprised to find that newsroom technology was behind that of many universities, since that was the word brought (or E-mailed) back from student interns and recent graduates of my program. In the end, my newsroom reentry that summer (I also worked at The Examiner and The Boston Globe other summers) helped me to feel confident that our journalism curriculum is on track. Although some of the ethical dilemmas faced by tundra reporters were dramatically different in detail than those of urban reporters, the soul-searching was similar, as were conceptual debates about whether the daily newspaper should be concerned with breaking news in this age of competing media or in writing more magazine- style pieces of depth and style. We should do both and we train students accordingly.

Because of the way my career has gone, I’ve been hanging out with teenaged journalists ever since I was editor of my high school newspaper.

One disturbing quality many young people share with veteran journalists today is cynicism, distinct from healthy skepticism. But how can they help it? They are exposed to infotainment, respected anchors hawking their books on network news, hyped “true life” stories, celebrity gossip masquerading as news. And some of my best students tell me they can’t afford to go into journalism, especially newspapers, because low starting salaries won’t put meaningful dents in student loans. (A good argument for the terrific journalism educations offered at many public institutions, but small comfort to students struggling to meet the costs of large private universities.)

Other students are turned off by invasions of privacy committed in the name of the people’s right to know. They get upset at the rudeness of reporters and incensed at the misallocation of news resources where swarms of reporters cover the same story while many other important stories go uncovered. I tell my students at the start of each semester that they will learn to be more sophisticated news consumers as well as more logical thinkers and writers. We discuss “trial balloons,” ethical lapses, omissions and commissions, and we deal with a new challenge in teaching reporting: getting some of our high-tech students to do in-person and telephone interviews for their stories. They’d rather get all of their information from the ’Net.

Many of our best graduates are lured by on-line jobs, but soon find that the initial excitement of going with a brand-name company in a big city wears off when they spend their shifts repackaging bits of news reported by someone else into a flashy Web presentation. Some of our more satisfied graduates are ones who took jobs in the boondocks, covering and uncovering news that’s critical to the functioning of communities and that no one else is writing about. They know they are making a difference, getting immediate feedback (tips, criticism, accolades), being known around town as “the reporter”—in short, practicing journalism.

Many in my generation are concerned about diversity, but many of my students don’t think it’s an issue. Of course, I don’t recall dwelling on these issues myself until I’d been in the working world awhile. For quite some time now, the majority of journalism students have been female, yet the majority of our faculty is still male; the chairs of all three departments and the dean of the college are all men, with female support staff. Whether you’re a good writer, reporter or teacher is not determined by gender, of course, but I wonder about the impact of these daily visual reminders. I often hear from former students, now journalists, who call to ask my opinion about whether treatment of them and their stories is happening because of something anyone might encounter, or is it because of being black? A woman? Latino?

At this point, the questions they ask me are very different than when they were students. A few don’t even deal with such issues as gender, appearance, ethnicity, unless they choose to.

In my own education, the best teachers I ever had were two remarkable middle-aged, white, male journalists. (Of course, I never had an opportunity to compare this with what impact women professors might have had.) The most intense course I took, including later studies at Stanford and Harvard, was Editorial Writing from Gene Graham, also the first person to mention the Nieman program to me. He made us read extensive histories of Indochina and introduced us to the writing of Malcolm Browne, David Halberstam and Ward Just. He showed us a piece he’d written about the Birmingham church bombings. His spare language and vivid detail made us feel the horror of those girls’ deaths without ever telling us what to think. Graham made sure we knew the background and context of what we planned to editorialize about before we disgorged our undergraduate opinions.

It was the academic year 1967-68. Protests against the Vietnam War were escalating, even at the socially conservative University of Illinois, with its huge engineering and agricultural colleges, and, when I started, strict curfews for women students. My final editorial series was on abortion, then illegal. In my conference on the series, Graham looked at the paper, then at me. “This is good,” he drawled, a self-described “good old boy” from Tennessee. “But does your Daddy know you’re writin’ about this?”

Given today’s sensibilities, his remark would have been considered sexist. I just laughed, savoring my teacher’s rare compliment. In those days, classrooms and newsrooms were more formal; professors and editors dressed in jacket and tie. I don’t recall feeling any discrimination or discouragement, although I was adamant that I not be assigned to the women’s page on my first newspaper job, the summer I was 19. It was clear to me what was women’s work. I knew I did not want to do it.

When I first taught, I tried to emulate my Illinois professors. I dressed in suits and was very strict. Following the dictates of Graham, a Pulitzer winner, I flunked students if they misspelled a name or reported inaccurately. “I always feel like throwing up after your class,” one young woman confessed. I required students to report each matter addressed at a City Council meeting, in declining order of importance, just as I had been taught. I sent them to court and called the prosecutors and defense attorneys to check their facts. If they garbled the story, they got bad grades and had to rewrite.

My best training as a teacher came from those long-ago lessons of Graham and another former newspaperman then at Illinois, Charles Puffenbarger, known to all as “Puff.” As a longtime colleague of his once observed, it was “not that he dealt condescendingly or too softly, as one might suspect of a professor known to students openly by his nickname. He was demanding, and expecting the best of his students, very often got it.”

Expecting the best. Demanding. Being there for students.

A lot of people go into teaching not to nurture the next generation, but “to have time to write.” How many times I’ve heard that, in interviews with prospective faculty or casual conversations when people ask what I do. They want to know what I’ve written lately. Often, it’s comments on a student’s paper, not for publication and certainly not under my byline. Good teaching is a lot like good parenting: it takes quantity as well as quality time and a healthy mix of discipline and support, all time-consuming tasks.

A few years ago, I was called into the then-chairman’s office. He told me he thought I was being too hard on my students. They shouldn’t be failed for one or two little mistakes, especially if “they are trying hard.” He told me he thought I was under strain from my divorce and should “ease up” on grading, suggesting that my student evaluations would improve, everyone would be happier, and my merit pay might even be higher.

Hearing this made me miss the “old days” at the U of I. Professors were not there to try to make students happy. Such an idea would have been completely foreign. They were there to teach good journalism, perhaps to inspire us, but basically to prepare us for the real world where, if we got the name wrong, it could ruin a reputation and we—and our employer—could be sued for libel. This was serious business, and we’d better learn it right or get out. There was no coddling. Grade inflation hadn’t hit, nor had the pressure we now are under to accept excuses. We didn’t know much about their personal lives, and they didn’t know much about ours. It wasn’t considered relevant.

But as much as the encompassing culture has changed, the qualities that make a good reporter have not: strict attention to detail, fairness, thoroughness, accuracy. I’m partial to reporters who want to fulfill those watchdog and spotlight roles, keeping a watchful eye on whether taxpayer funds are being wisely used by public servants, illuminating the hidden corners of our society, and empowering the powerless. The best journalists, whatever their media, are always going to be the ones with energy, passion, persistence and confidence—enough to go after the story, but not so much that they seldom have second thoughts about whether they could have done better.

After 17 years of teaching journalism, I’m much more relaxed. I tell students the class is informal and flexible, but the standards are not. By far the best aspect of this job is discovering great young journalists. I often keep coaching them by E-mail or phone calls while they’re wrestling with stories, with difficult or indifferent editors, with whether to make a job change. If journalism teachers haven’t been working professionals, they won’t know how to respond to these questions, nor will they have a network of folks to whom they can point students. It is essential that teachers have track records in what they’re teaching and that they maintain those ties through freelance, summer or consulting work. The theory doctors—those who teach about a profession they never practiced—have a place in academia, but it’s a separate one, in departments addressing communication as a social science. I’m pleased that where I teach the university recognizes this distinction, with the Department of Journalism now headed by a former ASNE president, and a different home for mass communications, advertising and public relations.

I wish Graham were still teaching, but the health problems that propelled him from his Nieman year to Urbana got worse and multiplied. It was only after his death in 1982 that his widow, sorting through his things, found a notebook from his Nieman year in which he had sketched seminar guests. She sent it to Cambridge. Now those sketches are framed behind glass and hung in a place of honor. I think of him and his legacy each time I’m at Lippmann House.

There is not one path to becoming a good reporter or a good journalism teacher. I hope those who teach also continue to “do,” through programs such as ASNE’s or endeavors they devise. I hope the elite institutions, such as Harvard, will offer meaty courses in the theory, practice and ethics of journalism, a field with a pervasive influence on our lives. And, most of all, I hope that students drawn to journalism will find their own Grahams and Puffs to guide them with grace, wit, empathy, humility and humor.

Remembering them reminds me that teaching journalism can be an honorable calling.

Nancy Day is Co-Director of the On-Line and Print Journalism Program at Boston University where she is also an associate professor. She is a 1979 Nieman Fellow.