Three years ago, just after Dolly the sheep was cloned, a Chicago television talk show asked attorney Nanette Elster, a specialist in reproductive technologies, to debate the issue of cloning humans. Also on the show that day was a doctor in favor of advancing this research so that one day humans might use it. The host invited the doctor to speak first and introduced him with words of respect, referring to him as “a genius who leads infertile couples to the fertile delta.” He then allowed the doctor to take as long as he wanted to explain his position. When it was Elster’s turn to speak, the host’s introduction was not nearly as laudatory, nor was the time or attention she was given at all similar. Barely had she begun her rebuttal when the host motioned to a surprise group of additional guests, the royal blue-faced performance group, the Blue Man Group, to appear on the set. Members of Blue Man Group started lobbing cream cheese balls over Elster’s head into each other’s mouths, diverting attention from anything she might be saying.

It was an appalling display of how some media outposts treat coverage of these kinds of critical and curious topics. During my 21 years as a practicing attorney, law professor and author of books about reproductive and genetic technologies, I have had many opportunities to observe media coverage of these issues. And, on average, five reporters try to reach me every day for comment and background information to inform their stories. The day the Baby M surrogate mother case was decided more than 100 reporters called me. When Dolly was born, I had so many calls it was not possible to return even one-tenth of them. Perhaps it is not a coincidence that my telephone rings more often during “sweeps” week; producers realize that these stories have the potential to appeal to a wide audience.

Through all of this, I have been continually struck by the one-sided coverage I’ve seen in the broadcast media. There is a herd mentality that focuses on one approach to the subject and then, after milking it, switches to the opposite approach. Usually the one-sided coverage is not evident in a single show, as it was in the situation that Elster found herself in when her perspective was all but obliterated by a circus act. Generally, an entire show is devoted to a particular take on an issue. In fact, news and talk show producers who call me often have a particular viewpoint they want to ply and they are seeking a “talking head” to mouth that perspective. As a result, the broadcast coverage rarely, if ever, does justice to the complexities of these issues.

If we look at the issue of surrogate motherhood in terms of broadcast media coverage, we can locate some of these media trends that unfortunately continue today. During the early 1980’s, when surrogate motherhood became a topic of national debate, producers would call and ask me to appear on morning news shows. They’d tell me they wanted me to talk about what they called “the gift of life:” a woman unselfishly serving as a surrogate mother. I would try to explain that the issue was more complex. I’d describe how some women might be psychologically harmed by serving as the home for a fetus but losing a maternal connection with the child after birth. But the producers didn’t want to hear about this. Then, when surrogate Mary Beth Whitehead decided to keep the baby she had contracted to bear, all of a sudden those same producers were calling to ask me to discuss “reproductive prostitution.” Actually, they were asking me to talk about the same thing, surrogate motherhood, but in their quest for a simple story line they didn’t realize that they’d made a 180 degree turn in their portrayal of this issue. Again, though, they were not interested in conveying the broader, more complicated contexts, nor in sharing the fact with viewers that most surrogate arrangements seem to work out for all of the parties involved.

Reproductive and genetic technologies will continue to be of enormous interest to reporters—both print and broadcast—because they provide possibilities for telling compelling stories. There is the key ingredient of human interest—the couple desperate to have a child or the woman fearful that she will die from breast cancer as her mother did. There is a gee-whiz scientific angle, too, as new technologies seem to leap right out of science fiction and into doctors’ offices.

But this desire to focus on those who are desperate to find ways to have a biological child or on the science behind these advances can lead reporters to miss what, in my view, are some of the most important stories about what’s happening in this field. Because it isn’t possible to visually portray or to interview a potential child, scant attention is given to numerous studies that indicate that some of these technologies might pose real risks for the children. High order multiple births are heralded as medical “miracles” without attention paid to the statistic that 16 percent of the babies die in the first month of life. New options such as egg freezing are hyped by the press without acknowledgement of studies suggesting genetic damage to the eggs. And because reporters are accustomed to dealing with scientists as neutral experts, they tend to overlook one of the more troubling aspects of this research: the dramatic commercialization of academic and government science due to changes in the law during the 1980’s.

This latter circumstance has all the elements of what makes great storytelling—greed, conflict of interest, big business, politics and potential risks to patients. But these story lines are more difficult to dig out than ones that emerge from interviewing an infertile patient, and so are rarely told.

That said, some newspaper reporters are doing this kind of investigative work and finding compelling ways to tell these important stories. Rick Weiss, a reporter at The Washington Post, and Robert Lee Hotz, a reporter at the Los Angeles Times, have each provided in-depth coverage of some of the risks in the ever expanding fertility business. Mitchell Zuckoff, Alice Dembner and Matt Carroll, at The Boston Globe, researched and wrote a revealing series on “a billion-dollar taxpayers’ subsidy for pharmaceutical companies already awash in profits.” Their reporting pointed to the unfairness of private companies getting exclusive benefit of publicly funded research.

Tough reportorial scrutiny should be applied also to decisions of taxpayer-funded researchers at the National Institutes of Health as they patent genes for private gain and enter into commercial ventures with biotech companies. Of course, these types of articles are more difficult and time consuming to undertake; they require more research and run the risk of alienating important researchers and institutions that have been long-standing sources. But reporting such as this is crucial to providing the public with a more textured picture of what is happening with these technologies.

There remain many more aspects of these breakthroughs and practices that could use the kind of public attention that good reporting can elicit. Such potential areas of inquiry include the following:

- Deficiencies in informed consent at in-vitro fertilization clinics.

- Ways in which clinics routinely exaggerate success rates in their promotional advertisements.

- Consequences that arise from the misuse of fertility drugs.

- The practice some clinics engage in when they sell patients’ “excess” embryos to biotech companies for use in developing pharmaceutical products.

- The reason for errors in genetic testing and the consequences.

- The deficiencies of regulatory oversight for emerging technologies.

Along the way I’ve also had my share of strange encounters with the media. And these encounters have led me to have experiences that I would not otherwise have had, some of which sent my thinking in new and valuable directions. Others just served as momentary distractions or, even worse, as irritants. I was once asked by a reporter on a religious television station whether clones would have souls. I suggested that if the minister/host thought identical twins each had souls, then later-born twins, clones, would as well. I’ve sparred on Oprah with a woman who wanted to use her dead son’s sperm to create her own grandchild.

But more often than not, my contacts with reporters have benefited my own work by serving as a sort of early warning system. They find out what is happening in my field before anyone else. They learn about the local couple who are suing over custody of a frozen embryo or of a judge’s decision to stop an employer from doing genetic testing. I’ve found that the quickest way to get information about developments in reproductive and genetic technologies is to have a reporter fax it to you. I learned about the cloning of Dolly before the rest of the world did because Gina Kolata, a reporter at The New York Times, called me for an advance comment on it. Of course, such information flows enhance coverage as well, by allowing the expert to comment more knowledgeably on the scientific research or legal case at issue.

Also, by keeping an eye on what news shows are covering in this field, I am able to get a pretty good sense of what people care about. This habit also gets me out of the ivory tower of academia where faculty members assume everyone cares about the same things they do. It propels me into the popular culture arena where I find out what issues these concerns of mine will have to compete with in order to be made part of the political conversation. And it also reminds me what opposing arguments sound like.

It was, after all, an experience on television that taught me how truly specialized scientists are. I was on “CBS Morning News” with a scientist who specialized in gene therapy. The host asked him a question about how many diseases could be screened for while the fetus was growing. I was aware of at least 350 disorders that could be assessed through amniocentesis. However, this gene therapy researcher (who did not do prenatal diagnosis) answered “three.” The lesson I learned that morning is one I hope reporters will have learned by the time they start asking questions for coverage of these stories.

I’ve also witnessed ways in which researchers can misstate the facts or the law to achieve their goals. On one news show I was on, an in-vitro fertilization doctor said that she told her patients that embryo donation is illegal in her state (which was not true) and encourages her patients to donate their excess embryos to her for use in her own research. On a PBS broadcast soon after the public disclosures that the Department of Energy had undertaken radiation experiments on people without their knowledge or consent, the Marcus Welby-looking doctor who appeared on the show with me assured the audience that no improper experimentation was going on at his hospital. I knew of such research there, but had been bound by confidentiality not to disclose it.

In short, working with members of the media provides the perfect training ground for addressing these issues in the policy sphere. Like many in the media, lawmakers’ attention spans are short. They have many other matters on their plates and they might be receiving erroneous or misleading advice from groups who are likely to be subject to the potential regulations.

Increasingly, it seems, these two domains—media and politics—are intersecting. Legislators are drawn to issues that can garner them publicity. For example, a swarm of Illinois state lawmakers introduced bills to ban human cloning immediately after Richard Seed, an independent scientist, set the media world afire with his vow to do just that in his state. That these laws duplicated ones already languishing without action in the Illinois legislature was overlooked in the rush for new publicity. Rather than vote on those, Johnny-come-lately lawmakers introduced their own bills in order to be able to hold press conferences that the press dutifully covered. The reporters did not do a good job of informing the public that similar bills already existed. And the quickest that I have ever been able to get a bill introduced was when, on the Phil Donahue show, I mentioned a problem with anonymous donor insemination. All of a sudden, a Washington, D.C. councilman who had seen the show had introduced a bill to deal with my concern. (That particular bill didn’t pass.)

Relying on the media is surely not the best way to craft policy in this country. Too often the ideas that take hold are ones that can be explained in a catchy phrase or pithy sound bite. These are not always the ideas or issues that really need to be understood if sound policy decisions are to be made. “We don’t believe in sound bites,” one PBS producer said, trying to lure me on his show by promising the unusual chance to discuss issues in depth. He went on to explain what it was he wanted: “We believe in more light, less heat.” I thought to myself, “Now that’s the perfect sound bite.”

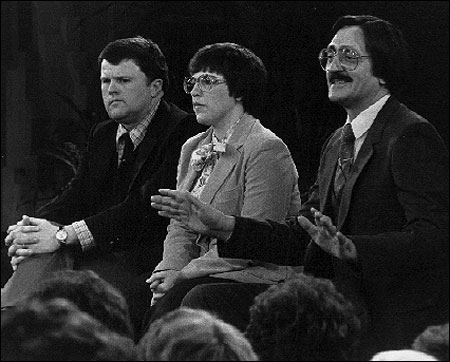

Surrogate mother Judy Stiver and her husband, Ray, left, of Lansing, Michigan, and Alexander Malahoff, who contracted with the Stivers for the birth of the infant, “Baby Doe,” appear on Phil Donahue’s show. The baby was born with microcephaly. Blood tests show Malahoff, of Middle Village, New York, was not the father. Photo by Charles Knoblock courtesy of AP.

Lori B. Andrews is a professor at Chicago-Kent College of Law and author of “The Clone Age: Adventures in the New World of Reproductive Technology,” published by Henry Holt and Company in the spring of 1999.