Andrea McCarren, husband Bill, and, from left, Olivia, Blake and Callaway pose for a family picture in the Badlands National Park in South Dakota.

Three days after covering the Obama inauguration, I was part of an unexpected mass layoff at WJLA-TV, the ABC affiliate in Washington, D.C.

I was among 26 journalists who lost their jobs that winter day. So I simply did what comes naturally in the 21st century. I updated my Facebook status.

“Andrea McCarren was just laid off,” I wrote, “and is enormously grateful for her 26-year run in television news.”

Like many random postings on the Internet, this one had unintended consequences. It was how my husband, Bill McCarren, learned of my job loss. A friend, who happens to be a newspaper reporter, phoned him and said, “What’s this news about Andrea?” To which Bill, replied, “Huh?” She said, “There was something on Facebook and it looks like she was laid off.” Bill fell silent.

“You’re telling me something I don’t know,” he said. “Let me find out and I’ll call you back.” As the general manager of the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., Bill had been in a series of meetings that morning and hadn’t even had the chance to check his e-mail or voice mail. I’d left messages on both.

Social media, I learned that day, was like a wildfire, spreading rapidly across the Internet, with little possibility of containment. My Facebook posting immediately led to a flood of phone calls, condolence e-mails, and job leads. A Facebook friend I’d met in person just one time introduced me to a high-profile CEO and entrepreneur who flew me to California for a job interview the next week. Former colleagues and even several interns I’d mentored in the past spoke to their bosses and paved my way into their news operations within days. No one was hiring but it boosted my spirits to make so many contacts.

I’d never lost a job before so this was all new territory for me. And I had no idea what it meant to be laid off in the public eye. Since my bio was immediately removed from my former television station’s Web site and I had to turn in the cell phone (and number) I’d had for more than a decade, loyal viewers and longtime sources looked for me online. A simple Google search turned up my Facebook page so hundreds of people friended me and wrote remarkably kind notes of support and encouragement.

Unbeknownst to me, colleagues, friends and viewers had also started tweeting the news of my layoff. My social media family grew exponentially, not just on Facebook and Twitter, but with a sea of new invitations to connect through LinkedIn.

And that was just the beginning. An editor at The Washington Post tracked me down through Facebook and asked me to write about what it was like to cover the tumultuous economy and then become part of the story. In addition, Howard Kurtz, the longtime media critic for the Post and the host of CNN’s “Reliable Sources,” found me through Facebook and asked if I would be a guest on his upcoming show about the battered journalism industry.

My essay in that Sunday’s Outlook section of the Post and subsequent appearance on CNN prompted more than 2,000 e-mails and letters from around the world. The leading Dutch newspaper wrote a column about me in the context of the troubled American economy. A crew from Taiwan Television came to my home to shoot a similar piece. I had suddenly become a poster child for the financial crisis in the United States.

This turbine in Lamar, Colorado is part of the fifth largest wind farm in the world. Photo by Andrea McCarren.

On the Road With Social Media

My family and I were awed by the compassion and kindness of Americans who wrote to me, most of whom I’d never met. They shared their own heart-wrenching experiences with layoffs and other catastrophic events and, importantly, they offered advice on how they got back on their feet.

I felt empowered and grateful, and we all knew we had to do something with this valuable material. So in August, with an idea and a rented RV, my husband, three children, and I hit the road.

Our plan was to travel across the United States and learn how others faced economic hardship, often reinvented themselves, and bounced back. I did what I’d done my entire career—interviewed strangers, wrote about them, and took photographs—and posted our progress and location daily on Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter.

By now, we knew the power of social media so I’d only set up a few stories in advance of our trip. We had a file full of leads and relied on Facebook and other social media for the rest.

Aside from food and clothing, we packed one computer, lots of road maps, still and video camera gear, and an abundance of faith that this would work.

It did. The stories we found stretch for miles and generations. We dubbed our journey “Project Bounce Back’’ and traveled through 21 states.

A Facebook friend suggested we visit Manistee, Michigan and look into the story of an auto parts plant that collapsed under the weight of the economy. Somehow the plant had reopened its doors to a new industry: building small wind turbines. The general manager, who had to lay off his entire staff, was thrilled to rehire and retrain many of those workers. We all donned safety glasses as he proudly showed us around his recrafted facility.

Social media contacts led us to towns that impressed us with their ability not just to survive hardship but to thrive. The residents of Greensburg, Kansas lost everything but their spirit in a deadly tornado. They vowed to rebuild better than before and emerged as a model of sustainable energy for the United States and the world.

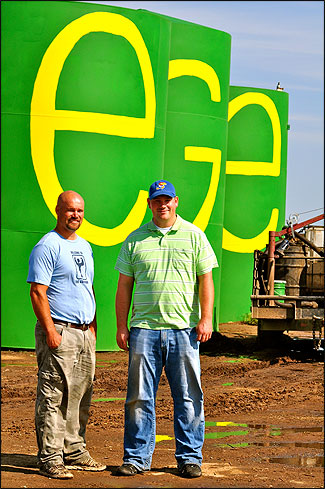

Just down the road, we found ourselves standing in a field of the grain milo with the Jaeger brothers, Luke and Matthew. With their father, the Jaegers cooked up a batch of biodiesel in their kitchen and found a homemade solution to the skyrocketing cost of gas. That discovery also helped them save their family farm.

Facebook friends guided us across South Dakota to the tiny town of Lead. There, the economy had forced the closure of its major employer, a gold mine. Refusing to accept financial defeat, the resilient folks of Lead are now preparing to open the nation’s first underground science laboratory in the old mine, a move that is attracting worldwide attention.

That story allowed us to spend the night a few hours south in the Black Hills Wild Horse Sanctuary, where we awoke at sunrise to the sounds of whinnying.

“You’re looking at the bare bones of an old cowboy’s dream,” the sanctuary’s 84-year-old founder, Dayton Hyde, told us. With 750 wild mustangs to feed and a dramatic drop in donations and grant money, the aging cowboy was a portrait of resilience, sheer grit, and determination. “It’s an awesome responsibility,” he said, “Buying 1,000 tons of hay for the winter. There’s no getting around it.”

Throughout our journey Facebook friends and LinkedIn contacts, most of whom were strangers, offered us their homes, the use of their cars, and home-cooked meals.

Two weeks into the trip, my husband announced, “This is like going on vacation with 1,000 friends!” I’m sure he meant it in a good way.

Social media provided the majority of our story leads as well as suggestions for some wonderful side trips including Oxford, Mississippi and Sun Studios in Memphis. After posting an update noting that we were handed Pepcid tablets upon entering the Iowa State Fair, we received an urgent Facebook message sending us to a friend’s brother who was exhibiting Belgian horses there.

Along the way, our RV rolled past breathtaking and meaningful landscapes. In southwest Minnesota, we were awed by the sight of hundreds of wind turbines against a Maxfield Parrish sunset—a field of white pinwheels, each punctuated by a bright red light at its center. And we parked our RV and slept in countless Wal-Mart parking lots, chatting with greeters and shelf stockers on the overnight shift.

On the third week of our trip, my 12-year-old daughter announced that the RV smelled “like one giant sock.” Social media postings allowed us to keep it real, too.

On the back roads of America, we found inspiration and hope and changed our family forever. We now feel confident and optimistic about the future, but what will I do next? Just check my Facebook status.

Brothers Luke, left, and Matthew Jaeger helped save the family farm by cooking up their own biodiesel in the kitchen. Photo by Andrea McCarren.

The Black Hills Wild Horse Sanctuary in Hot Springs, South Dakota is home to 750 wild mustangs. Owner Dayton Hyde calls it “the bare bones of an old cowboy’s dream.” Photo by Callaway McCarren.

Andrea McCarren, a 2007 Nieman Fellow and veteran television reporter, most recently covered immigration issues and the economy. She and her family launched www.projectbounceback.com to document their travels and the stories of hope and resilience that emerged along the way. Andrea is on Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter