The news business may be fading, but media criticism is a growth industry. Once relegated mainly to the alternative press, where scraggly anti-establishmentarians would rail against “the Man,” as represented by whatever major metropolitan newspaper was close at hand, these days documenting the sins of the media is a favored activity of cable pundits, think tanks of the left and right, and an ever expanding multitude of bloggers.

Yet surely few children hope to be media critics when they grow up—even those drawn to what they imagine as the glamour and excitement of journalism. The accidental nature of my own experience might be typical. In 1993 when I was working as a mid-level editor at The Boston Phoenix, the political columnist left; I asked for the job and was turned down. The following year the media critic’s position opened up. I asked and, this time, I received, and have been working the beat ever since—though in various media, print first, now online and on television.

As a critic of journalism with a long background in its practice, I admire most the press analysts who back up their judgments with reporting, research, style and wit—from A.J. Liebling to modern practitioners such as Jack Shafer of Slate, David Carr of The New York Times, Howard Kurtz of The Washington Post, and Eric Alterman of The Nation. Media criticism can take many forms. But the best is still journalistic at its heart.

The rise of blogging has changed media criticism, in some cases for the better, in some cases not. From the time I began blogging in 2002, I’ve found it incredibly liberating to have the material I need instantly at my disposal, and to be able to comment on it in real time. There’s something more honest about linking to the work I am slamming or praising. If I’m off the mark, my readers let me know immediately.

Indeed, much of media criticism today consists of a multi-directional conversation that would have been inconceivable in the early 1990’s. But the fragmentary nature of blogging has taken many of us, including me, away from the long, deeply reported pieces. It’s still journalism, but of a different kind. I hope it’s not of a lesser kind.

But media criticism as journalism is only one means by which it can be carried out. Other means—political activism, outside agitation, and efforts at institutional reform—can be just as, if not more, effective in bringing about change. For journalists, their work is the end of the process; for activists, it’s just the beginning.

Media Critics as Advocates

This second school of media criticism is the main concern of Arthur S. Hayes in his book “Press Critics Are the Fifth Estate: Media Watchdogs in America.” A media scholar at Fordham University and a former journalist, Hayes rates critics by such criteria as whether they have forced the dismissal of a wayward reporter, a change in content, reform of a news organization’s practices, or public debate.

By adopting effectiveness as his principal criterion, Hayes pays scant attention to any number of highly regarded media critics—including, he pointedly notes, the great Liebling. Instead, he devotes a chapter to Reed Irvine, founder of the right-wing organization Accuracy in Media (AIM). Hayes’s argument is that Irvine warrants such attention because of his success in the early 1980’s at intimidating PBS into adding “balance” to a controversial documentary on the Vietnam War. (Irvine’s tactics, Hayes observes, included “impugning” a specific reporter’s patriotism and making “unfounded accusations.” A disclosure: I have been subjected to precisely such treatment at the hands of Irvine’s successors at AIM so my assessment of Hayes’s take is based in part on personal experience.)

If AIM stands as Hayes’s paradigm of a naughty but effective advocacy group, he balances that with a chapter on Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), whose media criticism, he assures us, is as scrupulously accurate and carefully documented as it is left-leaning.

Yet, something feels odd in the lavish attention Hayes devotes to AIM and FAIR. I’d argue that each has long since given way to newer, more agile groups that are less out of the mainstream ideologically and more effective at capturing the attention of the media. For conservatives, L. Brent Bozell III’s Media Research Center and its various offshoots (most notably NewsBusters.org) have supplanted AIM and are taken far more seriously by fair-minded journalists. For liberals, David Brock’s Media Matters for America is a deep, well-researched source of information on outrageous statements by right-wing pundits such as Rush Limbaugh and Glenn Beck, and it is not nearly as far to the left as FAIR.

To be sure, Hayes shows us how Media Matters helped bring down Don Imus (temporarily) after he referred to the African-American players on the Rutgers’ women’s basketball team as “nappy-headed hos.” But this relatively recent example only partly offsets Hayes’s decision to treat FAIR and AIM as being significant actors.

Elsewhere, Hayes makes better choices. He profiles Ben H. Bagdikian, the godfather of the now-moribund ombudsman movement and author of “The Media Monopoly” and “The New Media Monopoly”—prescient books on the rise of huge media conglomerates in the 1970’s to 90’s. He tells the story of Jay Rosen and the civic journalism movement, a partly successful effort at media reform that has given way to the far more influential citizen journalism revolution, for which Rosen is a leading voice. He recounts the tale of how the blogswarm took down Dan Rather and how Jon Stewart’s on-air critique of CNN’s painfully shallow “Crossfire” may have hastened that program’s demise. (Second disclosure: I pop up briefly, as does Nieman Reports, in Hayes’s chapter on the short-lived magazine Brill’s Content.)

I find Hayes’s dry, academic approach unsatisfying. By contrast, I opened my yellowed copy of Liebling’s “The Press,” published in 1964, and happened upon this: “As for Mr. Lippmann, perhaps the greatest on-the-one-hand-this writer in the world today, he appeared to be suffering from buck fever when confronted with so magnificent an opportunity for indecision.” It sings, and you don’t even have to know what buck fever is to hear the melody. (My dictionary defines it as “nervous excitement felt by a novice hunter at the first sight of game.”)

At its best, media criticism—like all good journalism—is about digging out uncomfortable facts and telling them fearlessly. It is difficult to do well and, it shouldn’t be the critic’s job to bring about change. Truth is a rare enough commodity that it ought to be valued for its own sake.

Hayes’s book is a worthwhile if idiosyncratic survey of a certain kind of media criticism. But to understand how the journalists who travel in media criticism actually do their work—why they do things the way they do and how that process might be evolving in the digital age—the search for more insightful paths must continue.

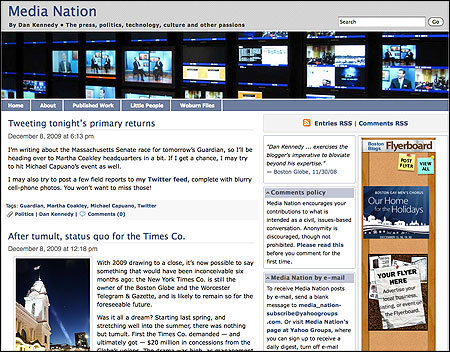

The homepage of Dan Kennedy’s Media Nation blog at www.dankennedy.net.

Dan Kennedy is an assistant professor of journalism at Northeastern University. He comments on media issues for “Beat the Press” on WGBH-TV in Boston, for The Guardian, and on his blog, Media Nation.

Yet surely few children hope to be media critics when they grow up—even those drawn to what they imagine as the glamour and excitement of journalism. The accidental nature of my own experience might be typical. In 1993 when I was working as a mid-level editor at The Boston Phoenix, the political columnist left; I asked for the job and was turned down. The following year the media critic’s position opened up. I asked and, this time, I received, and have been working the beat ever since—though in various media, print first, now online and on television.

As a critic of journalism with a long background in its practice, I admire most the press analysts who back up their judgments with reporting, research, style and wit—from A.J. Liebling to modern practitioners such as Jack Shafer of Slate, David Carr of The New York Times, Howard Kurtz of The Washington Post, and Eric Alterman of The Nation. Media criticism can take many forms. But the best is still journalistic at its heart.

The rise of blogging has changed media criticism, in some cases for the better, in some cases not. From the time I began blogging in 2002, I’ve found it incredibly liberating to have the material I need instantly at my disposal, and to be able to comment on it in real time. There’s something more honest about linking to the work I am slamming or praising. If I’m off the mark, my readers let me know immediately.

Indeed, much of media criticism today consists of a multi-directional conversation that would have been inconceivable in the early 1990’s. But the fragmentary nature of blogging has taken many of us, including me, away from the long, deeply reported pieces. It’s still journalism, but of a different kind. I hope it’s not of a lesser kind.

But media criticism as journalism is only one means by which it can be carried out. Other means—political activism, outside agitation, and efforts at institutional reform—can be just as, if not more, effective in bringing about change. For journalists, their work is the end of the process; for activists, it’s just the beginning.

Media Critics as Advocates

This second school of media criticism is the main concern of Arthur S. Hayes in his book “Press Critics Are the Fifth Estate: Media Watchdogs in America.” A media scholar at Fordham University and a former journalist, Hayes rates critics by such criteria as whether they have forced the dismissal of a wayward reporter, a change in content, reform of a news organization’s practices, or public debate.

By adopting effectiveness as his principal criterion, Hayes pays scant attention to any number of highly regarded media critics—including, he pointedly notes, the great Liebling. Instead, he devotes a chapter to Reed Irvine, founder of the right-wing organization Accuracy in Media (AIM). Hayes’s argument is that Irvine warrants such attention because of his success in the early 1980’s at intimidating PBS into adding “balance” to a controversial documentary on the Vietnam War. (Irvine’s tactics, Hayes observes, included “impugning” a specific reporter’s patriotism and making “unfounded accusations.” A disclosure: I have been subjected to precisely such treatment at the hands of Irvine’s successors at AIM so my assessment of Hayes’s take is based in part on personal experience.)

If AIM stands as Hayes’s paradigm of a naughty but effective advocacy group, he balances that with a chapter on Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), whose media criticism, he assures us, is as scrupulously accurate and carefully documented as it is left-leaning.

Yet, something feels odd in the lavish attention Hayes devotes to AIM and FAIR. I’d argue that each has long since given way to newer, more agile groups that are less out of the mainstream ideologically and more effective at capturing the attention of the media. For conservatives, L. Brent Bozell III’s Media Research Center and its various offshoots (most notably NewsBusters.org) have supplanted AIM and are taken far more seriously by fair-minded journalists. For liberals, David Brock’s Media Matters for America is a deep, well-researched source of information on outrageous statements by right-wing pundits such as Rush Limbaugh and Glenn Beck, and it is not nearly as far to the left as FAIR.

To be sure, Hayes shows us how Media Matters helped bring down Don Imus (temporarily) after he referred to the African-American players on the Rutgers’ women’s basketball team as “nappy-headed hos.” But this relatively recent example only partly offsets Hayes’s decision to treat FAIR and AIM as being significant actors.

Elsewhere, Hayes makes better choices. He profiles Ben H. Bagdikian, the godfather of the now-moribund ombudsman movement and author of “The Media Monopoly” and “The New Media Monopoly”—prescient books on the rise of huge media conglomerates in the 1970’s to 90’s. He tells the story of Jay Rosen and the civic journalism movement, a partly successful effort at media reform that has given way to the far more influential citizen journalism revolution, for which Rosen is a leading voice. He recounts the tale of how the blogswarm took down Dan Rather and how Jon Stewart’s on-air critique of CNN’s painfully shallow “Crossfire” may have hastened that program’s demise. (Second disclosure: I pop up briefly, as does Nieman Reports, in Hayes’s chapter on the short-lived magazine Brill’s Content.)

I find Hayes’s dry, academic approach unsatisfying. By contrast, I opened my yellowed copy of Liebling’s “The Press,” published in 1964, and happened upon this: “As for Mr. Lippmann, perhaps the greatest on-the-one-hand-this writer in the world today, he appeared to be suffering from buck fever when confronted with so magnificent an opportunity for indecision.” It sings, and you don’t even have to know what buck fever is to hear the melody. (My dictionary defines it as “nervous excitement felt by a novice hunter at the first sight of game.”)

At its best, media criticism—like all good journalism—is about digging out uncomfortable facts and telling them fearlessly. It is difficult to do well and, it shouldn’t be the critic’s job to bring about change. Truth is a rare enough commodity that it ought to be valued for its own sake.

Hayes’s book is a worthwhile if idiosyncratic survey of a certain kind of media criticism. But to understand how the journalists who travel in media criticism actually do their work—why they do things the way they do and how that process might be evolving in the digital age—the search for more insightful paths must continue.

The homepage of Dan Kennedy’s Media Nation blog at www.dankennedy.net.

Dan Kennedy is an assistant professor of journalism at Northeastern University. He comments on media issues for “Beat the Press” on WGBH-TV in Boston, for The Guardian, and on his blog, Media Nation.