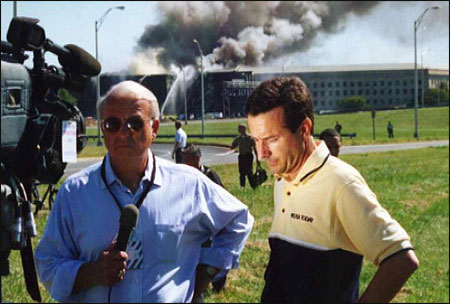

Mike Walter, right, prepares to go live with a report for WUSA, the CBS station in Washington, D.C. after the 9/11 attack on the Pentagon. Photo by Bob Pugh.

It’s happening again.

The man sitting next to me is crying. He’s fighting the tears, but the tears are winning and right now he’s like a prizefighter who has been knocked to the canvas, wobbly but determined to go on. After a long pause, he spits out two words, connected in spirit, but separated by time. The first is “I’m.” Then he shakes his head and finally, choking back more tears, blurts out “Sorry.” He’s ashamed of his tears, upset with himself for displaying this emotion.

Gary Tippet, one of the finest journalists in Australia, is also my friend. A senior writer at The Age, a leading daily in Melbourne, he’s won the Walkley, the Australian version of a Pulitzer. I’m watching Gary as he glances down and shakes his head. Then I look out at the audience. The room is packed and I’d describe the crowd as hanging on Gary’s every word, but actually they’re absorbed by his every tear because words aren’t yet being spoken. I glance over at his remarkable wife, Jeni, and I see tears rolling down her cheeks. She knows this pain her husband carries because she lives with it.

Eventually the words will come, but it will take time. I lift my arm, reach over and grab Gary’s shoulder, and say quietly, “It’s OK.” My hand is on his arm, but I know that my friend isn’t here. His body is in this room but as he tells the story, his mind is drifting back to that day—a day he knows he will never forget.

Gary knocks on the door, and as he does, in a ghastly turn of events, he realizes his mistake. He has arrived on the day of the boy’s funeral. It is too late to do anything about it. He has come to speak to a father whose child has wrapped his car around a telephone pole. There at the wake, he can’t help but feel uncomfortable. Everyone is there to pay their last respects, to mourn a teenager taken too young. But Gary is there for a story.

At the newspaper and police station, the young boy is a number—a number Gary will never forget. Through his tears, he says this, with a certain sense of shame. The boy is number 76. Gary will tell number 76’s story, but he will be haunted by the fact that he did not do the same for the other 75 who came before him. This teenager was the 76th person to die in a fatal wreck in Melbourne that year. There will be more—more pain and agony.

Gary knows he will be there at moments like this one, doing what he does, listening to, then telling these stories. Remarkably, on this day, the boy’s father agrees to talk. He has thought it through, and he says if talking to Gary can help save one child, it will be worth it. Journalists are accustomed to hearing these words. But what happens next is what has stayed with Gary all these years later.

Gary tells the audience that the father insisted that they talk in his son’s bedroom. So there, surrounded by the artifacts of a young life cut short, the father begins. As they sit together in this room, tears flow from the father’s eyes, just as they do from Gary’s as he recounts the story years later.

Gary is speaking in a large conference room at the Westin Hotel in Indianapolis. He’s part of a panel at the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) convention brought together to discuss “Breaking News, Breaking Down,” a film I made about journalists covering tragedy and trauma, and some of the issues it raises in the newsroom and in their personal lives. SPJ moved the screening to a bigger room after learning that a larger crowd was expected. People arrive in waves, and the screening is postponed as more chairs are brought in to accommodate everyone.

Those who came to watch the film did not expect to see what is happening now. Gary is clearly in the room with them, but emotionally it is apparent that he has rejoined this father on the bed in his son’s room. And as Gary speaks, the father is talking about the journey to the morgue. He identifies his boy, his flesh and blood. He tells Gary how he must hold him one last time. As he wraps his arms around his son, the tears drain from his eyes and he feels something crawling on his arms. His son had been thrown from the car and spent hours in the grass. The ants had claimed him before his father had a chance to hold him one last time.

As Gary recounts this story, there are more tears. That day in the bedroom Gary asked the questions; he fought the urge to cry. He did his job. Later, back in the newsroom late into the night and alone with the father’s words reverberating in his head, Gary began to craft one of his remarkable stories. Only then did the tears cascade down his cheeks and onto the keyboard.

A Film Reveals Journalists’ Trauma

For this collection of stories about journalists and trauma, I was asked to write about “Breaking News, Breaking Down.” Writing about the documentary is easy, but I’m not sure it’s as important as the emotions that the film evokes from journalists such as Gary and other members of the audience. It’s the little film that sparks a big reaction.

“Breaking News, Breaking Down” tells the story of my witnessing the American Airlines jet slamming into the Pentagon on 9/11. That day affected me in ways I never could have imagined. I’d seen my brother grapple with post-traumatic stress disorder when he returned from Vietnam, but somehow I never saw the same symptoms in myself, even when others did. After that day, I was haunted by nightmares, gripped by depression, and lived my life in a constant fog. I thought I was alone, but soon learned I was not. This film traces my journey as I met other journalists who were similarly affected by their work, from coverage of 9/11 to Hurricane Katrina.

I am grateful for the media coverage of my film. I’ve noticed, though, that none of it talks about the audience’s response. They get to me. I remember telling someone that this film is really about permission—the permission for people like Gary to open up about these buried experiences. There are many like Gary who have told their stories after watching this documentary—journalists, paramedics, Iraq War veterans, therapists and Vietnam vets.

Each exists in a world of trauma. A young therapist thanks me for making the film: “It made me think about what I absorb. It taught me to take my own emotional pulse. I will see a counselor when I return home.” A woman who was inside the Pentagon when the plane hit and another who was outside the World Trade Center hug me and thank me for making the film.

The film is therapeutic. In telling my story, I somehow have told theirs, too. When I was in Australia, I heard from Katrina Kincaid. Years ago she was a young producer at the Australian Broadcasting Corporation when she got her first overseas assignment. She was excited to be assigned to cover the war in Lebanon, but that feeling evaporated weeks later when she was clutching her soundman as he died in her arms. She hadn’t spoken about what happened that day in years, but she talked about it after seeing the film.

When the lights dim, I always have that funny feeling in my stomach. Mine is a deeply personal film and it exposes me in a way that would make others uncomfortable. But I know when the lights come up, magical connections will happen. I’ve watched the film over and over again; I know how it begins, what happens in it, and how the story ends. I cannot predict what will happen next. I only know there will be stories like Gary’s, and I will never forget his nor the ones I will one day hear others tell.

I began by talking about Gary, and his story is important in showing me that I am not alone. Journalists can remain objective while still absorbing on a human level what we observe. Yet after 9/11, I felt like a misfit as I asked myself why. Why me? Why was I there that day? Why was I reacting this way? It didn’t occur to me to ask the question that boy’s father asked himself on the day of his son’s funeral. He asked how—how could he take this tragedy, this horrible occurrence, and make something good out of it?

It would take me years to ask that fundamental question, then eventually find a way to create something good out of the experience of bearing witness to such a tragedy. This is what I hope I’ve accomplished with this film. I’ll never forget the people who have shed tears as they’ve told their stories. I have a saying that God never would have created tear ducts if he didn’t want us to use them. Soon, I’ll be off to the next screening, the next talk, and I’ll be prepared to put my hand on a shoulder, lean over and say, “It’s OK.’’

Mike Walter, the writer and director of “Breaking News, Breaking Down,” is a broadcast journalist who worked most recently as weekday anchor at WUSA, Washington, D.C.’s CBS station. He takes his documentary to film festivals, journalism conferences, and universities while keeping a journal about his experiences. Information about the film can be found at www.breakingnewsbreakingdown.com.