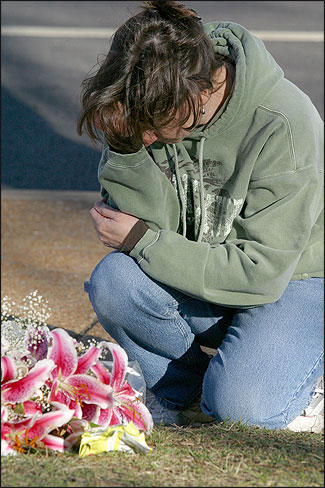

The community of Kirkwood, Missouri mourned the loss of police officers and city officials after a shooting at city hall on February 7, 2008. Covering the aftermath proved to be an emotional ordeal for members of the local media. Photo by Diana Linsley/Webster-Kirkwood Times.

Don Corrigan discussed the Kirkwood shooting on the Febuary 5, 2010 episode of NPR's "On the Media."On the evening of February 7, 2008, a large, angry man—whom I had once put on the front page of the hometown newspaper as a model citizen—went on a shooting spree at our local city hall. He pumped rounds into two police officers, two City Council members, the city engineer and the mayor. As a bystander to the event, a reporter from Lee Enterprise’s Suburban Journals was shot in the hand.

The carnage only stopped when police officers entered city hall and brought down Charles “Cookie” Thornton in a hail of bullets. Our community weekly was not known for covering horrendous crimes. Our reputation was for stories such as the one, years earlier, about Thornton serving as a reading volunteer for young children in the Kirkwood School District.

Kirkwood, a town in suburban St. Louis that had fancied itself as a sort of Mayberry, was more accustomed to our upbeat stories. The town was not ready for a photograph full of tears and a banner headline, “A Community Mourns,” as we covered the hastily arranged funerals. Readers were not ready for the community weekly to be packed with the details of murder at city hall—and neither were we at the Webster-Kirkwood Times.

As I write this, it all still doesn’t ring true. How could Mayor Mike Swoboda, whom I chatted with on a local bike trail days before the shootings, now be gone? How could these people, whom I talked to on a regular basis for city hall stories, now be gone? How could Kirkwood Police Sgt. William Biggs Jr. and Council member Connie Karr, whom I had arranged to speak to my reporting class at the local college the very week of the killings, now be gone? How could this have happened?

These are lifetime questions that do not go away easily. I’ve learned this from other editors and reporters who’ve had to cover the murders of people they once knew closely. I’ve learned this from serving on media panels on “tragedies and journalists” and by becoming familiar with the work of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma which deals, in part, with helping journalists who endure a kind of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) reaction after their immersion in horrors they are called upon to cover.

Haunting questions of why such evil happens do not fall in the purview of editors and journalists. But there are less ethereal questions that can be addressed after being caught up in terrifying events. Among them:

- What is a news organization’s responsibility to its reporters who are eyewitnesses to murder? Can an editorial staff experience depression or long-term PTSD as a result of such exposure?

- What are the local news media’s obligations to the national news media as requests for background information and interviews pile up? In the case of a community weekly, when do we say “no” and take care of our own coverage and our own needs?

- When the national dailies, TV networks, and the cable news channel operations finally go away, what should the continuing coverage of the local news media operation be like? Can the content of such coverage help with the healing of a community, as well as a newspaper’s own staff?

What Happens Next?

When bits of news of the city hall massacre began airing as bulletins on local radio and television in St. Louis, our immediate concern was for our Times’ reporter, Marty Harris, who regularly covered city hall. Although she was not injured, she was directly behind the city engineer who was killed execution-style.

After a debriefing by police officials, we shielded Harris from a slew of interview requests. Then, she was allowed to take as much time off as she deemed necessary and she was offered counseling as were many employees of the city of Kirkwood. She has not covered city hall meetings since the tragedy.

Counselors provided a range of ideas on how to cope in the grim aftermath of the tragedy. Depending on personality traits, I learned that some prescriptives involved long vacation trips to help purge negative images from the mind. Vacations were advised for the duration of one-year memorial anniversary activities. Other counselors advised reporters to use their writing as a way to confront and to deal with emotions about the killings. They also advised that we come together to talk among ourselves about our feelings and how we were coping with conflicting emotions.

Vacation trips are not an option for everyone in a small news operation caught up in a community crisis. My own situation was compounded by the death of a close friend just days before the shootings, and then learning my dad was diagnosed with inoperable brain cancer days after the shootings. I found it impossible to sleep until I was prescribed a strong sedative by my doctor. My wife urged me to quit taking the pills because of concerns about dependency and personality changes.

I’d argue that some longlasting personality changes have taken place—with or without drugs—on the news-editorial side of our weekly operation since February 7, 2008. At the Webster-Kirkwood Times, we are kinder and gentler with each other. In our news and editorial department, there is less excitement over “big stories” breaking or at criticism from readers directed our way. Perhaps we are shell-shocked. Perhaps we presume we have been through the biggest and ugliest story of our journalism careers.

A memorial in front of city hall in Kirkwood, Missouri marked the loss of people who were murdered inside the building. Members of the media were among those who witnessed the shootings. Photo by Diana Linsley/Webster-Kirkwood Times.

The Human Touch

It is this journalist’s feeling that there should not be a double standard when it comes to granting interviews and being cooperative with others in the news media. If we believe that people in our community should be cooperative with us, then members of local press should cooperate with the national news media when interviews are requested.

In the aftermath of the Kirkwood shootings, our newspaper staff cooperated as much as possible by sharing past stories and pictures with the national news media. The front page feature photo from a decade earlier of the killer, “Cookie” Thornton, was shared and seen around the world. In most cases, the national news media credited the Times with the photo, but not always. The Times also opened its story archives on Thornton and deceased members of the community. However, there comes a time when those who work for a local newspaper have to do their own job; that can mean saying no to such requests for interviews.

For our small staff, the job of reporting and shooting photos at six funerals was overwhelming. Yet during that time, requests kept coming our way. There was a network morning TV show staffer who called me at home at 1:30 in the morning, just hours after the shootings. She pleaded with me to give up the home phone number of our reporter who witnessed the shootings. When I told this CBS employee I would not give up the phone number and that I would talk to Harris in the morning about whether she wanted to comply with this interview request, I was reminded about TV deadline demands.

When I still refused to give up the phone number, this person told me that the morning show and all of the United States “wanted to reach out to Marty and express sympathy.” Then I was told that CBS News anchor Katie Couric wanted to reach out to Harris. Finally, I was told that “my boss is going to kill me if I don’t get this interview.” I hung up. I was tempted to tell her that the Webster-Kirkwood Times would reach out to her family if her boss did, indeed, kill her.

In welcome contrast came a call from Chris Bury of ABC’s “Nightline” wanting to interview me about Thornton and the murders at city hall. We could not find a time that worked for both of us, largely because I was attending funerals, including one for my good friend. “Don’t worry about it. Forget it,” Bury said. “It’s more important now for you to be human.”

A Time to Heal

In the time since the city hall massacre, it has been important for us to be human as we go about doing our work. When asked, we have covered church and reconciliation meetings, and we’ve backed off when the request for privacy was made.

There was a racial component to these murders. Thornton was black; all the victims were white. A few in the minority community felt Thornton had legitimate grievances against the city and was pushed over the edge. Some of our white readers were offended that we covered Thornton’s funeral and that we quoted “his apologists” at subsequent forums for healing and understanding.

Our newspaper and its Web site covered many community forums, and such events are still happening. Some readers accuse us of dragging out the coverage of an aberration that is best forgotten. Others feel the incident needs more coverage, more analysis—and that we have sided with the “powers that be.” Most readers express support for our coverage, and for allowing a wide array of voices to be heard as we report on these community reconciliation forums.

A local Society of Professional Journalists’ meeting was very helpful in the EDITOR'S NOTE: Accounts such as those mentioned in Terri Weaver's talk have been compiled by the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma and are available at dartcenter.org.aftermath of the Kirkwood shootings. Editors and reporters who covered the city hall massacre attended and heard Terri Weaver, a trauma expert and professor of psychology at St. Louis University, explain that whole towns can be traumatized, as well as individuals, in the aftermath of extreme violence. As a Virginia Tech alum, Weaver is quite familiar with the trauma that the town of Blacksburg, Virginia has been going through as a result of the 33 shooting deaths on that campus. In her talk she acquainted us with accounts of journalists’ reactions to covering such tragedies.

Familiarity with the personal and professional issues involved with this kind of coverage would help a lot before an event catapults us into it, as happened with us. And the Dart Center—and now Nieman Reports with this issue—offers useful guidance based on the lived experiences of journalists who share tips about ways to cope during and after the coverage of tragic events. Among the observations I’ve found especially cogent is this one from the Dart Center: “Journalists have a history of denial. There is a perception that you are unprofessional if ‘you can’t handle it.’ Journalists claim they are unaffected to their colleagues. But this false bravado takes its toll.”

Don Corrigan is editor and co-publisher of the Webster-Kirkwood Times and South County Times in suburban St. Louis and a professor of journalism at Webster University.