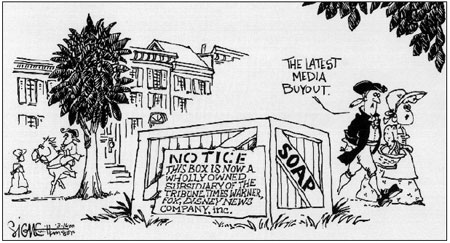

Cartoon by Signe Wilkinson. © 2000, The Washington Post Writers Group. Reprinted with permission.

Four months after the stunning news about plans to combine Viacom and CBS, this year began with the announcement of an even more spectacular merger—America Online and Time Warner. Faced with these giant steps toward extreme concentration of media power, journalists mostly responded with acquiescence.

Now, as one huge media merger follows another, the benefits for owners and investors are evident. But for our society as a whole, the consequences seem ominous. The same limits that have constrained the media’s coverage of recent mergers within its own ranks are becoming features of this new mass media landscape. For the public, nothing less than democratic discourse hangs in the balance.

“Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one,” A.J. Liebling remarked several decades ago. In 2000, half a dozen corporations own media outlets that control most of the news and information flow in the United States. The accelerating mergers are terrific for the profits of those with the deepest pockets, but bad for journalism and bad for democracy.

When the Viacom-CBS story broke, media coverage depicted a match made in corporate heaven: At more than $37 billion, it was the largest media merger in history. With potential effects on the broader public kept outside the story’s frame, what emerged was a rosy picture. “Analysts hailed the deal as a good fit between two complementary companies,” The Associated Press reported flatly. The news service went on to quote a media analyst who proclaimed: “It’s a good deal for everybody.”

“Everybody”? Well, everybody who counts in the mass media calculus. For instance, the media analyst quoted by AP was from the PaineWebber investment firm. “You need to be big,” Christopher Dixon explained. “You need to have a global presence.” Dixon showed up again the next morning in the lead article of the September 8 edition of The New York Times, along with other high-finance strategists. An analyst at Merrill Lynch agreed with his upbeat view of the Viacom-CBS combination. So did an expert from ING Barings: “You can literally pick an advertiser’s needs and market that advertiser across all the demographic profiles, from Nickelodeon with the youngest consumers to CBS with some of the oldest consumers.”

In sync with the prevalent media spin, The New York Times devoted plenty of ink to assessing advertiser needs and demographic profiles. But during the crucial first day of the Times’s coverage, foes of the Viacom-CBS consolidation did not get a word in edgewise. There was, however, an unintended satire of corporate journalism when a writer referred to the bygone era of the 1970’s: “In those quaint days, it bothered people when companies owned too many media properties.”

The Washington Post, meanwhile, ran a front-page story that provided similar treatment of the latest and greatest media merger, pausing just long enough for a short dissonant note from media critic Mark Crispin Miller: “The implications of these mergers for journalism and the arts are enormous. It seems to me that this is, by any definition, an undemocratic development. The media system in a democracy should not be inordinately dominated by a few very powerful interests.” It wasn’t an idea that the Post’s journalists pursued.

Overall, the big media outlets—getting bigger all the time—offer narrow and cheery perspectives on the significance of merger mania. News accounts keep the focus on market share preoccupations of investors and top managers. Numerous stories explore the widening vistas of cross-promotional synergy for the shrewdest media titans. While countless reporters are determined to probe how each company stands to gain from the latest deal, few of them demonstrate much enthusiasm for exploring what is at stake for the public.

With rare exceptions, news outlets covered the Viacom-CBS merger as a business story. But more than anything else, it should have been covered, at least in part, as a story with dire implications for possibilities of democratic discourse. And the same was true for the announcement that came a few months later—on January 10, 2000—when a hush seemed to fall over the profession of journalism.

A grand new structure, AOL Time Warner, was unveiled in the midst of much talk about a wondrous New Media world to come, with cornucopias of bandwidth and market share. On January 2, just one week before the portentous announcement, the head of Time Warner had alluded to the transcendent horizons. Global media “will be and is fast becoming the predominant business of the 21st century,” Gerald Levin said on CNN, “and we’re in a new economic age, and what may happen, assuming that’s true, is it’s more important than government. It’s more important than educational institutions and nonprofits.”

Levin went on. “So what’s going to be necessary is that we’re going to need to have these corporations redefined as instruments of public service because they have the resources, they have the reach, they have the skill base. And maybe there’s a new generation coming up that wants to achieve meaning in that context and have an impact, and that may be a more efficient way to deal with society’s problems than bureaucratic governments.” Levin’s next sentence underscored the sovereign right of capital in dictating the new direction. “It’s going to be forced anyhow because when you have a system that is instantly available everywhere in the world immediately, then the old-fashioned regulatory system has to give way,” he said.

To discuss an imposed progression of events as some kind of natural occurrence is a convenient form of mysticism, long popular among the corporately pious, who are often eager to wear mantles of royalty and divinity. Tacit beliefs deem the accumulation of wealth to be redemptive. Inside corporate temples, monetary standards gauge worth. Powerful executives now herald joy to the world via a seamless web of media. Along the way, the rest of us are not supposed to worry much about democracy. On January 12, AOL chief Steve Case assured a national PBS television audience on “The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer”: “Nobody’s going to control anything.” Seated next to him, Levin declared: “This company is going to operate in the public interest.”

Such pledges, invariably uttered in benevolent tones, were bursts of fog while Case and Levin moved ahead to gain more billions for themselves and maximum profits for some other incredibly wealthy people. By happy coincidence, they insisted, the media course that would make them richest was the same one that held the most fulfilling promise for everyone on the planet.

Journalists accustomed to scrutinizing the public statements of powerful officials seem quite willing to hang back from challenging the claims of media magnates. Even when reporting on a rival media firm, journalists who work in glass offices hesitate to throw weighty stones; a substantive critique of corporate media priorities could easily boomerang. And when a media merger suddenly occurs, news coverage can turn deferential overnight.

On March 14—the day after the Tribune Company announced its purchase of the Los Angeles Times and the rest of the Times Mirror empire—the acquired newspaper reported on the fine attributes of its owner-to-be. In a news article that read much like a corporate press release, the Times hailed the Tribune Company as “a diversified media concern with a reputation for strong management” and touted its efficient benevolence. Tribune top managers, in the same article, “get good marks for using cost-cutting and technology improvements throughout the corporation to generate a profit margin that’s among the industry’s highest.” The story went on to say that “Tribune is known for not using massive job cuts to generate quick profits from media properties it has bought.”

Compare that rosy narrative to another news article published the same day, by The New York Times. Its story asserted, as a matter of fact, that “The Tribune Co. has a reputation not only for being a fierce cost-cutter and union buster but for putting greater and greater emphasis on entertainment and business.”

“It is not necessary to construct a theory of intentional cultural control,” media critic Herbert Schiller commented in 1989. “In truth, the strength of the control process rests in its apparent absence. The desired systemic result is achieved ordinarily by a loose though effective institutional process.” In his book “Culture, Inc.,” subtitled “The Corporate Takeover of Public Expression,” Schiller went on to cite “the education of journalists and other media professionals, built-in penalties and rewards for doing what is expected, norms presented as objective rules, and the occasional but telling direct intrusion from above. The main lever is the internalization of values.”

Self censorship has long been one of journalism’s most ineffable hazards. The current wave of mergers rocking the media industry is likely to heighten the dangers. To an unprecedented extent, large numbers of American reporters and editors now work for just a few huge corporate employers, a situation that hardly encourages unconstrained scrutiny of media conglomerates as they assume unparalleled importance in public life.

The mergers also put a lot more journalists on the payrolls of mega-media institutions that are very newsworthy as major economic and social forces. But if those institutions are paying the professionals who provide the bulk of the country’s news coverage, how much will the public learn about the internal dynamics and societal effects of these global entities?

Many of us grew up with tales of journalistic courage dating back to Colonial days. John Peter Zenger’s ability to challenge the British Crown with unyielding articles drew strength from the fact that he was a printer and publisher. Writing in The New York Weekly, a periodical burned several times by the public hangman, Zenger asserted in November 1733: “The loss of liberty in general would soon follow the suppression of the liberty of the press; for it is an essential branch of liberty, so perhaps it is the best preservative of the whole.”

In contrast to state censorship, which is usually easy to recognize, self censorship by journalists tends to be obscured. It is particularly murky and insidious in the emerging media environment, with routine pressures to defer to employers that have massive industry clout and global reach. We might wonder how Zenger would fare in most of today’s media workplaces, especially if he chose to denounce as excessive the power of the conglomerate providing his paycheck.

Americans are inclined to quickly spot and automatically distrust government efforts to impose prior restraint. But what about the implicit constraints imposed by the hierarchies of enormous media corporations and internalized by employees before overt conflicts develop?

“If liberty means anything at all,” George Orwell wrote, “it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.” As immense communications firms increasingly dominate our society, how practical will it be for journalists to tell their bosses—and the public—what media tycoons do not want to hear about the concentration of power in few corporate hands? Orwell’s novel “1984” describes the conditioned reflex of “stopping short, as though by instinct, at the threshold of any dangerous thought…and of being bored or repelled by any train of thought which is capable of leading in a heretical direction.”

In the real world of 2000, bypassing key issues of corporate dominance is apt to be a form of obedience: in effect, self censorship. “Circus dogs jump when the trainer cracks his whip,” Orwell observed more than half a century ago, “but the really well-trained dog is the one that turns his somersault when there is no whip.” Of course, no whips are visible in America’s modern newsrooms and broadcast studios. But if Orwell were alive today, he would surely urge us to be skeptical about all the somersaults.

Norman Solomon’s weekly column on media and politics is distributed to newspapers by Creators Syndicate. His latest book is “The Habits of Highly Deceptive Media: Decoding Spin and Lies in Mainstream News.”