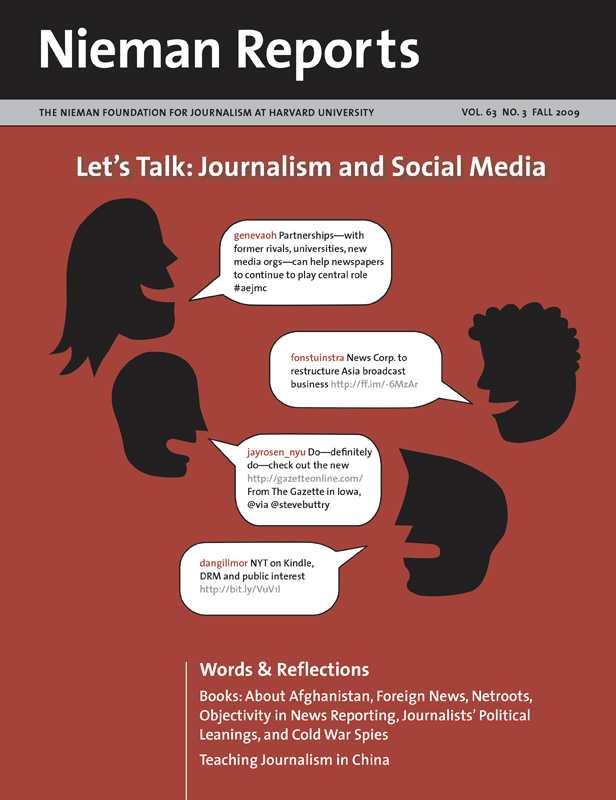

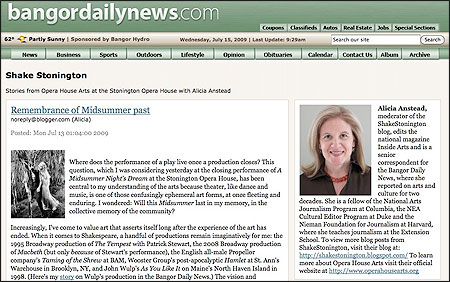

Anstead moderated a blog, which appeared on www.bangordailynews.com/shake-stonington.html, for a project called “Shakespeare and the Journalist in the 21st Century.”

Galen Koch had her first Shakespeare moment the summer she was 14. She and two young friends were cast in “Romeo and Juliet” for the annual Shakespeare production at the Stonington Opera House on Deer Isle in Maine, and their excitement was uncontainable.

“We were totally in love with the love and the poetry of ‘Romeo and Juliet,’” says Koch, who grew up on the island and is now 20. “And that was when I fell in love with Shakespeare, that was the ‘aha’ moment.”

If you have an “aha” moment with Shakespeare in your past, then you know how lucky Koch is to have had such a revelation when she was just Juliet’s age. For me, an “aha” moment came last year when my job as chief arts reporter and critic for the Bangor Daily News ended, and another possible use for my journalistic skills opened up with a previously unthinkable connection to a performing arts center.

Shakespeare in Stonington, where Koch got her start, is an annual event performed by professional actors from New York City and seen by upward of a thousand audience members who live in or visit this remote, rural fishing village once renowned for its granite quarries.

I regularly wrote about the Stonington Opera House for my newspaper and The New York Times—so I knew that not just the Shakespeare was excellent. The programming, in general, was among the best I had seen in Maine or any place else, frankly.

My first assignment at the Opera House was in 2001, a full two years after Linda Nelson, Judith Jerome, Carol Estey, and Linda Pattie, the founding partners of Opera House Arts, purchased the dilapidated historic building, an old vaudeville venue, hoping to rejuvenate both the structure and its cultural legacy in the community. The event was not Shakespeare but an art equally unlikely in such a far-off setting: jazz. Through the years I had attended many performances in rustic settings—barns, garages, abandoned storefronts. This is not unusual for Maine. And yet, something provocative happened that night, and it began as I rounded the corner of Main Street, with the churning harbor on one side of me and the craggy rise of earth on the other. There, in a space between, wedged into a steep wall of granite as if teetering precariously on a cliff, was the Opera House, corporeal and incontrovertible. What happened inside the hall was even more notable. Not to work the granite metaphor too hard, but this place rocked.

I knew that first night—and was bolstered in my opinion later that summer with a stunning production of “The Tempest”—that the Opera House had a vibe I had rarely seen at other performing arts centers in Maine.

Similar to the traveling theater companies that visited Stratford-on-Avon during Shakespeare’s childhood, the Opera House troupers arrive in Stonington, where they board in the homes of island residents, eat lobster and fried clams, walk among the citizenry, march in the Fourth of July parade, and put a human face to theater—while also working indoors for 10 long days finalizing preparations for opening night.

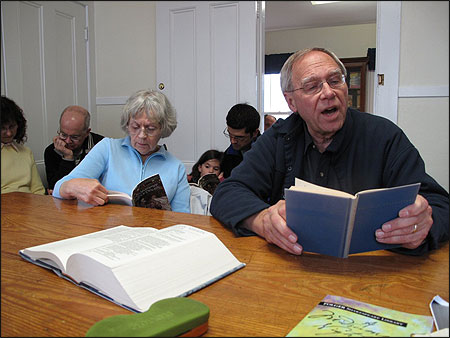

As a complement to the stage work in the past two years, the Opera House has held community “reads” at local libraries: As many as 20 people sit around a table and speak the text out loud, occasionally stopping to explicate a line, word or thought. The process is always revelatory, and those who start out shy often end up stars. Or at least starry eyed. One woman was in tears toward the end of “Macbeth,” when Macduff slays the king. She understood the flawed humanity behind Macbeth’s tyranny, and it made her feel sympathy for, of all people, Saddam Hussein.

By the time of “Macbeth” in 2008, I had spent a year as the inaugural arts and culture fellow at the Nieman Foundation and, at the completion of that year, my full-time arts reporting position had, much like the Scottish king, been slain by a coup of another kind: technology over print, the news story over in-depth arts coverage.

That’s when Opera House Artistic Director Judith Jerome and Executive Director Linda Nelson asked me to lead the library reads and to conduct a post-show talk-back with a Shakespeare scholar and members of the creative team. The professional ease and naturalness of the events sparked not only my imagination but Linda’s, too.

Anstead interacted with community members, summer visitors, and theater professionals as she put her reporting skills to use in new ways, in concert with a production of Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream’’ at the Stonington Opera House in Maine. Photo by Carolyn Caldwell.

Embedded Journalism

A journalist herself, Linda saw the possibility for another kind of “embedded journalism”—in much the same way the actors embedded, literally, in the community. The term entered the lexicon with reporters in Iraq who boarded tanks with soldiers and went out into the night wearing flak jackets and helmets while carrying notebooks and cameras. The result was an immediate, if controversial, connection to the action. Linda saw that same possibility for the arts. What if an arts journalist embedded herself in the community, applying her reporting and analytical skills to a production of Shakespeare?

I might not have considered doing this work with any other arts organization. It mattered to me that the Opera House upholds the highest standards for Shakespeare, convening auditions in New York City and scrupulously choosing theater artists—directors, designers, composers, actors—committed to reinterpreting Shakespeare, such as “The Taming of the Shrew” set in a women’s prison, “Hamlet” with a silent movie patina, and “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” as an Amazon’s drugged dream.

Both the Maine Arts Commission, which awarded me an Artist Visibility Grant, and the Bangor Daily News, which distributed our content, saw the value in “Shakespeare and the Journalist in the 21st Century,” the title for a project that revolved around a production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” at the Opera House this summer.

Notice I wrote “our content” because, while I moderated the blog, facilitated community reads, and led two talk-backs for this project, the administrative and artistic staff and even the audience contributed, shaping coverage with new voices and insights. They opened a window to the process, to the lives of artists and arts administrators and to the experience of art. For my part, I hoped to create access to perspectives the reader might not find in other places: videos of theatergoers’ responses to the show, photos from the community reads and production, links to additional material about Shakespeare, and audio interviews with leading Shakespeare scholars and theater artists such as Harvard professor Stephen Greenblatt and Diane Paulus, director of the Tony Award-winning Broadway revival of “Hair.’’

All our voices mashed online. It was an odd and yet fulfilling relationship for me—the embedded journalist. In pre-blog, pre-Facebook, pre-Twitter years, an editor might wave a reporter away from stepping this close to the flame of art and artists. But this was a test run for all of us, a potential model for arts reporting at a time when an estimated half of all the staff arts reporting jobs in this country have been eliminated.

Frankly, it was more honest on some level: I have always believed the arts critic is more closely connected to the artist, more passionate about the craft than we openly admit. Oscar Wilde saw the critic as artist and while I won’t go that far, I can see the value of giving up the seat on the aisle for a seat at the table. Despite the decisions of newspaper investors and publishers, we still need arts arbiters in the community to foster dialogue, to debate, to ask the questions, to think along with audiences about what they have seen and how they feel. We need dialogue about the arts because the arts help us understand private moments and global leaders.

We haven’t found a magic formula for keeping the critic’s voice and experience available and funded, but we’ve tested the waters for a new relationship, and it worked. I did my journalism. The Opera House had packed audiences. Shakespeare was in the drinking water. Do I continue to wonder about the evaluative role of the critic? Ah, there may be the rub. But I no longer wonder if there is a new possibility for creating a place for the voices that help us to understand, know, think about, and digest art.

Members of an island community in Maine read aloud from “A Midsummer Night’s Dream’’ at a read facilitated by Anstead. Photo by Alicia Anstead.

Photo by Alicia Anstead.

Alicia Anstead, a 2008 Nieman Fellow, is editor in chief of Inside Arts magazine. She also is an arts consultant, freelance writer, and journalism instructor at Harvard Extension School. Her work with Opera House Arts is at Shakestonington.blogspot.com.