One day in 1988, an angry Enos Nkala, Zimbabwe’s Defense Minister, called The Chronicle, a government-owned regional daily newspaper, to order the editor and his deputy to report to his office. If they failed to respond to his summons, he warned, he would send soldiers to drag them out of their offices.

Geoff Nyarota and his deputy, Davison Maruziva, didn’t go to the minister’s office. Instead, they intensified their investigation on the issue that had earned them the wrath of the minister. The paper had been investigating irregular deals at the state-owned Willowvale Mazda Motor Industries, a car assembly plant, in which ministers and other senior government officials were abusing their office to gain from the public corporation millions of dollars. They would buy cars cheaply, as they were officially entitled to do, but would then resell them at exorbitant prices, depriving government of revenue and enriching themselves unfairly.

The Chronicle’s investigative reports were so embarrassing to the government that President Robert Mugabe appointed a judicial commission of inquiry to investigate the matter. The commission’s findings vindicated the newspaper’s reports and several ministers resigned in disgrace. Enos Nkala was among them.

Willowgate, as the scandal came to be called, earned the two journalists dire retribution. Nyarota was “promoted” to a management position (as director of public relations) which was specially created for him in the Zimbabwe newspapers group. The journalists who had worked under him in the Willowvale stories were also reassigned.

Zimbabwe’s Free, But Can the Press be Free?

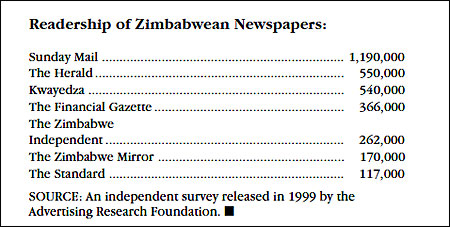

The country, which gained independence from Britain in 1980, has during the last decade experienced the birth of a vibrant independent press which has found its niche in a market that is still dominated by state-controlled news organizations. The government controls Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC), the nation’s only radio and television broadcaster, Ziana, a national news agency, the Community Newspapers Group (CNG), which publishes several regional newspapers, and Zimbabwe Newspapers Ltd. (Zimpapers), which publishes The Sunday Mail, The Herald, The Sunday News, The Chronicle, and Kwayedza (A Shona-language weekly).

The growth of the media has been aided by Zimbabwe’s advanced level of literacy. With a population of 12.5 million, it has the highest literacy level (85 percent) in Africa. The country’s journalism is fairly sophisticated and many newspapers have adopted modern publishing technology, including online editions.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Imprisonment and Torture of Journalists in Zimbabwe"

- Mark G. ChavundukaMugabe’s government accuses those who work for independent media of engaging in sensational and irresponsible reporting that is harmful to the state. Early in 1999, Zimbabwe came under sharp international focus when two journalists working for The Standard were arrested, illegally detained by the military, and tortured for publishing a story alleging a failed coup plot. Editor (and Nieman Fellow ’00) Mark Chavunduka and his senior writer, Ray Choto, had to seek treatment in London after their release. Shortly after this episode, the editor and publisher of The Zimbabwe Mirror, Ibbo Mandaza, and his reporter, Grace Kwinjeh, were also charged for publishing an alarming report. The previous year the paper had published a story alleging that a Zimbabwean soldier had died in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and his body had been brought back to the country without a head for burial. The charges were later dropped.

The government is determined to get its way and maintain a firm grip on what is published.

Who, If Anyone, Will Control the Media?

Last year, the Ministry of Information prepared a draft bill to control the media. The bill, which was presented to the Cabinet for approval, has not yet been tabled in Parliament to be passed into law.

The new media policy framework proposes the formation of either a statutory or non-statutory body to define media ethics and standards and to accredit journalists. It also deals with the issue of media ownership and stipulates that foreigners should only own between 20 and 25 percent of Zimbabwe’s media and that they should not sit on editorial boards. If the framework passes, it will also be a crime for a foreigner to use a Zimbabwean as a front to establish a media business in the country. The bill further requires any foreigner who wants to invest in the country’s media to declare his financial capacity before being authorized to make the investment.

Those who work in the independent press have condemned the proposed law. They have dismissed it as a government attempt to enhance authoritarianism. Members of the press have proposed coming up with a mechanism of self-regulation. Senior editors from the mainstream media have formed a committee to look into ways of forming a body that will carry out this task. “We prefer self-regulation by the media because the government cannot be trusted to have the interest of the media at heart. The regulation they want to put in place is not sincere,” says Trevor Ncube, group editor in chief for The Zimbabwe Independent.

Ncube believes journalists should establish a press complaints council to handle concerns of those who feel individual reporters, the corporate world or the government has unfairly treated them. The council should not be mandated to punish offenders but it should have “enough teeth” to compel offending members of the media to apologize or correct stories if they are proved to be inaccurate.

The Zimbabwe Union of Journalists (ZUJ), the trade union, has also condemned the government’s proposed law. “Media workers should use all means necessary to ensure that all oppressive laws are discarded. If it means throwing stones to get press freedom, we have to do it to render certain pieces of legislation unconstitutional,” says Basildon Peta, ZUJ’s Secretary General. The union has come up with its own proposals in which it calls for a provision in the constitution to guarantee freedom of the press. It suggests that a media council be formed with members drawn from the media, the government, and stakeholders from other sectors. The union says the council should be funded by the government and answerable to Parliament. Its mandate should include issuing of licenses and handling complaints against media organizations that engage in wayward and malicious reporting. A separate independent broadcasting authority should be set up to govern operations of the electronic media.

Issues that the press-proposed media council would be expected to address include guidelines about how members of the media should relate to the public and among themselves. Corruption among journalists is another issue which the council is expected to deal with. In the past, journalists have been accused of receiving bribes from individuals, institutions and government in exchange for positive coverage. In 1998, two journalists working for The Sunday Mail were arrested while in the act of receiving a Z10,000 (U.S. $240) bribe from a Harare restaurant owner so that they would give his business positive coverage. They are now facing extortion and corruption charges.

The government defends its proposed media law by saying it is not aimed at muzzling media freedom but at regulating it to safeguard the interests of the public. “Although the government wants the media to operate in a favorable environment, it is necessary to retain some laws which act as checks and balances against journalists who report irresponsibly,” says Willard Chiwewe, Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Information.

Difficulties in Trying to Reform the Media

Amid discussion about how the press in Zimbabwe might be monitored, some independent evaluations are already identifying problems in how news is being conveyed to the public. The Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA) is a media advocacy body whose mission is to foster free, independent and diverse media throughout Southern Africa. It has chapters in several countries including Zimbabwe (MISA-Zimbabwe). Under the aegis of MISA, the Media Monitoring Project was established in 1999 to act as watchdog of the performance of the press in Zimbabwe. In its first report, the project castigated the performance of the public media, accusing it of being unprofessional and harboring a deliberate agenda to misinform the public.

There are some in Zimbabwe who feel that the present media growth has not been broad based enough to be of maximum benefit to the society. Dr. Tafataona Mahoso is the head of the Division of Media and Mass Communication at Harare Polytechnic, the leading training ground for journalists. He believes that lack of resources and a cultural bias have made Zimbabwean media urban-based and therefore not fully people-centered. “The media in Zimbabwe reflects the world-view of urban dwellers, the middle class, while giving no voice to the rural folk. The media is supposed to be a catalyst of human development. It can only do this effectively if it makes a conscious attempt to reach everybody.”

Mahoso has had a chance to implement his vision. In 1997 he landed a presidential appointment as chairman of the board of directors of Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation. He was, however, booted out after barely a year in office after he unearthed corruption and tried to root it out. His board discovered many irregularities, including fraudulent hiring practices that gave birth to unprofessional practices. A report released at the beginning of 1999 by a 12-member parliamentary committee set up to investigate the fiasco revealed a series of vices including corruption, nepotism, political patronage, and sex abuse in the hiring of staff.

Mahoso’s experience illustrates the dilemma facing senior staff working for the state-owned media. They find themselves at a crossroads, struggling to maintain professional ethics and at the same time remaining loyal to their bosses. As a result, senior editorial positions have had to be given not necessarily to people who are professionally competent but to those who will be amenable to the state’s manipulation.

Economic Troubles Doom Some Publications

The fight for media freedom now focuses on a campaign to ensure the eradication of draconian laws that the government uses to stifle freedom of expression. The Law and Order Maintenance Act (LOMA), which was enacted in 1960 by the colonial government to contain the struggle for self-determination by blacks, has been broadly criticized. It outlaws publication of material that is likely to cause fear, alarm and despondency among any section of the public or to bring the country’s leader to disrepute. In 1998, Parliament reacted to public criticism by passing the Public Order and Security Bill (POSB) to replace LOMA. Journalists and human rights groups condemned the new bill, saying it contained many elements of LOMA. President Mugabe refused to sign it into law and referred it back to Parliament for further discussion. In an accompanying letter to the Speaker of Parliament, he said that the bill didn’t deal adequately with journalists who might publish unsubstantiated reports.

Chavunduka and Choto successfully challenged a section of LOMA in the Supreme Court, arguing that it contradicts the constitutional guarantee for freedom of expression and therefore it should be declared null and void.

Another focus in the battle for media freedom has been to lobby the government to end its monopoly on the electronic media. By law, only ZBC is allowed to operate TV and radio broadcasts. Human rights and democracy activists say a more open society can only be created if all forms of media are liberalized. But the government has rejected the suggestion.

While the government’s media crackdown presents plenty of cause for concern, perhaps the most immediate and greatest threat to the press is their economic viability. At the beginning of the 1990’s, Zimbabwe, which had been pursuing socialist economic policies, adopted the IMF/World Bank reform program. Coupled with the abandonment of plans by the government to pass a law declaring Zimbabwe a one-party state, an era of economic and political liberalization was ushered in. In this relatively relaxed environment, the birth of new publications created a media boom. Several weekly papers, monthlies and periodicals were born. But the most significant product of this boom was a new daily newspaper, The Daily Gazette.

Hopes were high that this boom would lead to a radical transformation in the country’s media. Instead, Zimbabwe experienced a severe economic slump that shattered this dream. Consumer power was eroded. People didn’t have disposable income to buy the new products. Advertisers didn’t have money to spare. The little they had was used to advertise in the traditional government-owned media whose circulation they could count on.

With inflation pushing cost of production up, new media companies had a rough ride. Many eventually became casualties in the battle for survival. The Daily Gazette was an instant hit when it was established in 1992. At the peak of its success, it was selling 60,000 copies a day. For a new publication, this was impressive, especially when compared with the 130,000 daily copies of The Herald, a paper that had been published since 1891. This new daily infused freshness into the country’s media scene and offered readers a new source of news absent of government vetting. But the unfavorable economic climate forced the paper to cease publication after only three years.

Last year the media scene was altered when the Associated Newspapers of Zimbabwe (ANZ) was established. The company, which has 60 percent foreign ownership, launched five regional weeklies and capped this by launching Daily News in March 1999. ANZ poached the best journalists through offers of high salaries, and it was tipped to succeed where The Daily Gazette had failed to challenge the monopoly of the government in the daily press.

But the company soon plunged into a financial crisis. Less than a year after its launch, it shut down three weeklies. Investors admitted that their ambitious media venture faced collapse unless $1 million (U.S. dollars) was urgently injected to raise new operating capital. Last November, the Southern Africa Media Development Fund (SAMDEF), a Botswana-based non-governmental media organization that was established to strengthen the region’s media so they can become self-sustaining, independent and pluralistic, invested that amount of money in the company.

But it is not just the private press that is going through financial tribulations. During the last three years, the Zimpapers’ profit has fallen drastically and Ziana is on the verge of collapse due to the government’s lack of funding. Africa Information Afrique, a donor-funded international news agency, ceased operations last December.

Currently, only The Zimbabwe Independent and its sister, The Standard, appear to be on firm financial footing. Their success has widely been attributed to patronage by white-owned businesses that constitute more than 80 percent of the country’s economy. The government has often accused these newspapers of being used by whites to bring it down and possibly revive white rule.

Ncube angrily denies this link. “That is not true. We get 70 percent of our advertising support from black-owned companies. Our success has come about because we produce a high-quality product,” he says.

Mugabe’s government watches with silent glee as the independent press swims in the stormy seas of financial turmoil. The ruling party functionaries have continued their crusade against foreign investment in the country’s media, saying it is dangerous to national sovereignty.

Some journalists who have endured the difficulties of government interference and financial hard times still see a bright future. “Zimbabwe’s media will weather the storm and become one of the most vibrant in Africa,” says Ncube. “The present battles are inevitable in media development in any society.”

If his positive forecast turns out to be right, Zimbabwe could soon join the league of sub-Saharan countries such as Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa where the media, having fought similar battles, appear right now to be the victors. And given the results of the parliamentary elections in June, in which the opposition gained an impressive number of seats, it now appears more likely that the media in Zimbabwe might be headed for a radical transformation.

Just before the elections, which were marred by violence, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) took ZBC to court seeking an order to compel it to give fair coverage to all contestants. The order was successful, and the court ruled that the state broadcaster, which was accused of criminalizing the opposition, should air balanced reports on the activities of anti-Mugabe activists. Despite the court’s ruling, this did not happen.

After the election, Mugabe made 30 constitutional parliamentary appointees, thus inflating the ruling party’s slim electoral victory. Because of this, Parliament might not provide the opposition with a very influential voice. But the new multi-party Parliament will no doubt result in greater political liberalism, and this might, in turn, result in the country crossing the threshold of a new era of media freedom.

David Karanja, a Kenyan novelist and freelance journalist, lived in Zimbabwe for 13 months. His novel, “The Girl Was Mine,” was published in 1996. A second, “A Dreamer’s Paradise,” will be published next year by Kwela Books, South Africa.

Geoff Nyarota and his deputy, Davison Maruziva, didn’t go to the minister’s office. Instead, they intensified their investigation on the issue that had earned them the wrath of the minister. The paper had been investigating irregular deals at the state-owned Willowvale Mazda Motor Industries, a car assembly plant, in which ministers and other senior government officials were abusing their office to gain from the public corporation millions of dollars. They would buy cars cheaply, as they were officially entitled to do, but would then resell them at exorbitant prices, depriving government of revenue and enriching themselves unfairly.

The Chronicle’s investigative reports were so embarrassing to the government that President Robert Mugabe appointed a judicial commission of inquiry to investigate the matter. The commission’s findings vindicated the newspaper’s reports and several ministers resigned in disgrace. Enos Nkala was among them.

Willowgate, as the scandal came to be called, earned the two journalists dire retribution. Nyarota was “promoted” to a management position (as director of public relations) which was specially created for him in the Zimbabwe newspapers group. The journalists who had worked under him in the Willowvale stories were also reassigned.

Zimbabwe’s Free, But Can the Press be Free?

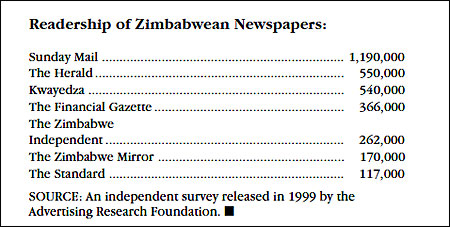

The country, which gained independence from Britain in 1980, has during the last decade experienced the birth of a vibrant independent press which has found its niche in a market that is still dominated by state-controlled news organizations. The government controls Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC), the nation’s only radio and television broadcaster, Ziana, a national news agency, the Community Newspapers Group (CNG), which publishes several regional newspapers, and Zimbabwe Newspapers Ltd. (Zimpapers), which publishes The Sunday Mail, The Herald, The Sunday News, The Chronicle, and Kwayedza (A Shona-language weekly).

The growth of the media has been aided by Zimbabwe’s advanced level of literacy. With a population of 12.5 million, it has the highest literacy level (85 percent) in Africa. The country’s journalism is fairly sophisticated and many newspapers have adopted modern publishing technology, including online editions.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Imprisonment and Torture of Journalists in Zimbabwe"

- Mark G. ChavundukaMugabe’s government accuses those who work for independent media of engaging in sensational and irresponsible reporting that is harmful to the state. Early in 1999, Zimbabwe came under sharp international focus when two journalists working for The Standard were arrested, illegally detained by the military, and tortured for publishing a story alleging a failed coup plot. Editor (and Nieman Fellow ’00) Mark Chavunduka and his senior writer, Ray Choto, had to seek treatment in London after their release. Shortly after this episode, the editor and publisher of The Zimbabwe Mirror, Ibbo Mandaza, and his reporter, Grace Kwinjeh, were also charged for publishing an alarming report. The previous year the paper had published a story alleging that a Zimbabwean soldier had died in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and his body had been brought back to the country without a head for burial. The charges were later dropped.

The government is determined to get its way and maintain a firm grip on what is published.

Who, If Anyone, Will Control the Media?

Last year, the Ministry of Information prepared a draft bill to control the media. The bill, which was presented to the Cabinet for approval, has not yet been tabled in Parliament to be passed into law.

The new media policy framework proposes the formation of either a statutory or non-statutory body to define media ethics and standards and to accredit journalists. It also deals with the issue of media ownership and stipulates that foreigners should only own between 20 and 25 percent of Zimbabwe’s media and that they should not sit on editorial boards. If the framework passes, it will also be a crime for a foreigner to use a Zimbabwean as a front to establish a media business in the country. The bill further requires any foreigner who wants to invest in the country’s media to declare his financial capacity before being authorized to make the investment.

Those who work in the independent press have condemned the proposed law. They have dismissed it as a government attempt to enhance authoritarianism. Members of the press have proposed coming up with a mechanism of self-regulation. Senior editors from the mainstream media have formed a committee to look into ways of forming a body that will carry out this task. “We prefer self-regulation by the media because the government cannot be trusted to have the interest of the media at heart. The regulation they want to put in place is not sincere,” says Trevor Ncube, group editor in chief for The Zimbabwe Independent.

Ncube believes journalists should establish a press complaints council to handle concerns of those who feel individual reporters, the corporate world or the government has unfairly treated them. The council should not be mandated to punish offenders but it should have “enough teeth” to compel offending members of the media to apologize or correct stories if they are proved to be inaccurate.

The Zimbabwe Union of Journalists (ZUJ), the trade union, has also condemned the government’s proposed law. “Media workers should use all means necessary to ensure that all oppressive laws are discarded. If it means throwing stones to get press freedom, we have to do it to render certain pieces of legislation unconstitutional,” says Basildon Peta, ZUJ’s Secretary General. The union has come up with its own proposals in which it calls for a provision in the constitution to guarantee freedom of the press. It suggests that a media council be formed with members drawn from the media, the government, and stakeholders from other sectors. The union says the council should be funded by the government and answerable to Parliament. Its mandate should include issuing of licenses and handling complaints against media organizations that engage in wayward and malicious reporting. A separate independent broadcasting authority should be set up to govern operations of the electronic media.

Issues that the press-proposed media council would be expected to address include guidelines about how members of the media should relate to the public and among themselves. Corruption among journalists is another issue which the council is expected to deal with. In the past, journalists have been accused of receiving bribes from individuals, institutions and government in exchange for positive coverage. In 1998, two journalists working for The Sunday Mail were arrested while in the act of receiving a Z10,000 (U.S. $240) bribe from a Harare restaurant owner so that they would give his business positive coverage. They are now facing extortion and corruption charges.

The government defends its proposed media law by saying it is not aimed at muzzling media freedom but at regulating it to safeguard the interests of the public. “Although the government wants the media to operate in a favorable environment, it is necessary to retain some laws which act as checks and balances against journalists who report irresponsibly,” says Willard Chiwewe, Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Information.

Difficulties in Trying to Reform the Media

Amid discussion about how the press in Zimbabwe might be monitored, some independent evaluations are already identifying problems in how news is being conveyed to the public. The Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA) is a media advocacy body whose mission is to foster free, independent and diverse media throughout Southern Africa. It has chapters in several countries including Zimbabwe (MISA-Zimbabwe). Under the aegis of MISA, the Media Monitoring Project was established in 1999 to act as watchdog of the performance of the press in Zimbabwe. In its first report, the project castigated the performance of the public media, accusing it of being unprofessional and harboring a deliberate agenda to misinform the public.

There are some in Zimbabwe who feel that the present media growth has not been broad based enough to be of maximum benefit to the society. Dr. Tafataona Mahoso is the head of the Division of Media and Mass Communication at Harare Polytechnic, the leading training ground for journalists. He believes that lack of resources and a cultural bias have made Zimbabwean media urban-based and therefore not fully people-centered. “The media in Zimbabwe reflects the world-view of urban dwellers, the middle class, while giving no voice to the rural folk. The media is supposed to be a catalyst of human development. It can only do this effectively if it makes a conscious attempt to reach everybody.”

Mahoso has had a chance to implement his vision. In 1997 he landed a presidential appointment as chairman of the board of directors of Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation. He was, however, booted out after barely a year in office after he unearthed corruption and tried to root it out. His board discovered many irregularities, including fraudulent hiring practices that gave birth to unprofessional practices. A report released at the beginning of 1999 by a 12-member parliamentary committee set up to investigate the fiasco revealed a series of vices including corruption, nepotism, political patronage, and sex abuse in the hiring of staff.

Mahoso’s experience illustrates the dilemma facing senior staff working for the state-owned media. They find themselves at a crossroads, struggling to maintain professional ethics and at the same time remaining loyal to their bosses. As a result, senior editorial positions have had to be given not necessarily to people who are professionally competent but to those who will be amenable to the state’s manipulation.

Economic Troubles Doom Some Publications

The fight for media freedom now focuses on a campaign to ensure the eradication of draconian laws that the government uses to stifle freedom of expression. The Law and Order Maintenance Act (LOMA), which was enacted in 1960 by the colonial government to contain the struggle for self-determination by blacks, has been broadly criticized. It outlaws publication of material that is likely to cause fear, alarm and despondency among any section of the public or to bring the country’s leader to disrepute. In 1998, Parliament reacted to public criticism by passing the Public Order and Security Bill (POSB) to replace LOMA. Journalists and human rights groups condemned the new bill, saying it contained many elements of LOMA. President Mugabe refused to sign it into law and referred it back to Parliament for further discussion. In an accompanying letter to the Speaker of Parliament, he said that the bill didn’t deal adequately with journalists who might publish unsubstantiated reports.

Chavunduka and Choto successfully challenged a section of LOMA in the Supreme Court, arguing that it contradicts the constitutional guarantee for freedom of expression and therefore it should be declared null and void.

Another focus in the battle for media freedom has been to lobby the government to end its monopoly on the electronic media. By law, only ZBC is allowed to operate TV and radio broadcasts. Human rights and democracy activists say a more open society can only be created if all forms of media are liberalized. But the government has rejected the suggestion.

While the government’s media crackdown presents plenty of cause for concern, perhaps the most immediate and greatest threat to the press is their economic viability. At the beginning of the 1990’s, Zimbabwe, which had been pursuing socialist economic policies, adopted the IMF/World Bank reform program. Coupled with the abandonment of plans by the government to pass a law declaring Zimbabwe a one-party state, an era of economic and political liberalization was ushered in. In this relatively relaxed environment, the birth of new publications created a media boom. Several weekly papers, monthlies and periodicals were born. But the most significant product of this boom was a new daily newspaper, The Daily Gazette.

Hopes were high that this boom would lead to a radical transformation in the country’s media. Instead, Zimbabwe experienced a severe economic slump that shattered this dream. Consumer power was eroded. People didn’t have disposable income to buy the new products. Advertisers didn’t have money to spare. The little they had was used to advertise in the traditional government-owned media whose circulation they could count on.

With inflation pushing cost of production up, new media companies had a rough ride. Many eventually became casualties in the battle for survival. The Daily Gazette was an instant hit when it was established in 1992. At the peak of its success, it was selling 60,000 copies a day. For a new publication, this was impressive, especially when compared with the 130,000 daily copies of The Herald, a paper that had been published since 1891. This new daily infused freshness into the country’s media scene and offered readers a new source of news absent of government vetting. But the unfavorable economic climate forced the paper to cease publication after only three years.

Last year the media scene was altered when the Associated Newspapers of Zimbabwe (ANZ) was established. The company, which has 60 percent foreign ownership, launched five regional weeklies and capped this by launching Daily News in March 1999. ANZ poached the best journalists through offers of high salaries, and it was tipped to succeed where The Daily Gazette had failed to challenge the monopoly of the government in the daily press.

But the company soon plunged into a financial crisis. Less than a year after its launch, it shut down three weeklies. Investors admitted that their ambitious media venture faced collapse unless $1 million (U.S. dollars) was urgently injected to raise new operating capital. Last November, the Southern Africa Media Development Fund (SAMDEF), a Botswana-based non-governmental media organization that was established to strengthen the region’s media so they can become self-sustaining, independent and pluralistic, invested that amount of money in the company.

But it is not just the private press that is going through financial tribulations. During the last three years, the Zimpapers’ profit has fallen drastically and Ziana is on the verge of collapse due to the government’s lack of funding. Africa Information Afrique, a donor-funded international news agency, ceased operations last December.

Currently, only The Zimbabwe Independent and its sister, The Standard, appear to be on firm financial footing. Their success has widely been attributed to patronage by white-owned businesses that constitute more than 80 percent of the country’s economy. The government has often accused these newspapers of being used by whites to bring it down and possibly revive white rule.

Ncube angrily denies this link. “That is not true. We get 70 percent of our advertising support from black-owned companies. Our success has come about because we produce a high-quality product,” he says.

Mugabe’s government watches with silent glee as the independent press swims in the stormy seas of financial turmoil. The ruling party functionaries have continued their crusade against foreign investment in the country’s media, saying it is dangerous to national sovereignty.

Some journalists who have endured the difficulties of government interference and financial hard times still see a bright future. “Zimbabwe’s media will weather the storm and become one of the most vibrant in Africa,” says Ncube. “The present battles are inevitable in media development in any society.”

If his positive forecast turns out to be right, Zimbabwe could soon join the league of sub-Saharan countries such as Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa where the media, having fought similar battles, appear right now to be the victors. And given the results of the parliamentary elections in June, in which the opposition gained an impressive number of seats, it now appears more likely that the media in Zimbabwe might be headed for a radical transformation.

Just before the elections, which were marred by violence, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) took ZBC to court seeking an order to compel it to give fair coverage to all contestants. The order was successful, and the court ruled that the state broadcaster, which was accused of criminalizing the opposition, should air balanced reports on the activities of anti-Mugabe activists. Despite the court’s ruling, this did not happen.

After the election, Mugabe made 30 constitutional parliamentary appointees, thus inflating the ruling party’s slim electoral victory. Because of this, Parliament might not provide the opposition with a very influential voice. But the new multi-party Parliament will no doubt result in greater political liberalism, and this might, in turn, result in the country crossing the threshold of a new era of media freedom.

David Karanja, a Kenyan novelist and freelance journalist, lived in Zimbabwe for 13 months. His novel, “The Girl Was Mine,” was published in 1996. A second, “A Dreamer’s Paradise,” will be published next year by Kwela Books, South Africa.