What kind of journalist will thrive in the emerging 21st century? One more adept than the 20th century version at teamwork, technology, marketing, business economics, and the anthropology of communities. No longer is it enough for reporters and editors to have a flair for language, an insatiable need to know, and a religious devotion to the First Amendment.

A majority of newspaper readers consider journalists out of touch with mainstream America. They believe the media is ignorant and arrogant in its coverage of local issues. A 1998 newspaper industry self-study also showed that:

- Journalists make so many factual, spelling and grammatical mistakes that readers are skeptical about their newspapers’ ability to get anything right.

- The public suspects journalists’ personal biases play a strong role in determining which stories are covered, how they are written, and how prominently they are displayed in the paper.

- Members of the public who have had actual experience with the news process are the most critical of the media’s credibility.

No wonder circulation figures have declined for nearly half a century.

This study by the American Society of Newspaper Editors led to an array of experiments to build reader trust. Two years later, though, concern over the future of the industry is still so deep that editors and publishers are undertaking the most extensive reader survey in history.

The results of that massive study won’t be unveiled until April. But already there is discussion about the kind of journalist needed to help turn things around and about the changes media organizations must make to attract and keep this new breed of journalist.

One thing is certain. Today’s journalists must temper their arrogance. This is the interactive age, epitomized by the Internet. Newspapers will need to move beyond their comfort zone as masters of monologue. Today’s journalists must welcome calls from readers, promptly answer a steady stream of e-mail from the public [see pages 28- 30], pay attention to focus groups, and spend more time getting to know everyday people rather than just those in the towers of power.

Journalists have already stopped assuming they know what is best for readers. Economics forced that shift. Many people are finding ways to stay informed without newspapers. To lure them back, journalists are striving to treat the public more and more as advisors, not just end users. “For their own survival, newspapers have had to become sensitive to what their communities want them to do,” says Bangor Daily News Executive Editor Mark Woodward.

That extends beyond just listening more intently to the public. It means journalists must begin schooling themselves in the anthropology of community building. They must understand the nature of alienation and the need for bonding to provide relevance, depth and analysis in a time-starved, information-soaked, solution-craving society. We are, after all, social animals. Newspapers must feed more than our intellect. They also must feed our hearts and souls.

Today’s journalists must be team players in another sense as well. Not only must they work more closely with their communities. They can no longer hide in their newsrooms when they are in the office.

- They must partner with their brethren in marketing to help tell their own story, something that in the past has been viewed as selfish, as boorish, even unethical. Reporters have long thought that the canon of objectivity meant they should let their words speak for themselves rather than engage in any promotion. But the economics of survival have convinced some journalists that marketing can be another way to get their story out.

- They must develop products jointly with the business side to better meet the needs of both readers and advertisers. For decades, journalists feared that working with the “money-grubbing revenue producers” would result in pressure to favor advertisers in news coverage. Indeed, the credibility crisis at the Los Angeles Times earlier this year proved that can happen. But the best-led newspapers will figure out a way to make these partnerships work without compromising their ethics.

- They will be partnering with their counterparts in television, radio and the Internet to better serve their “shared” customers.

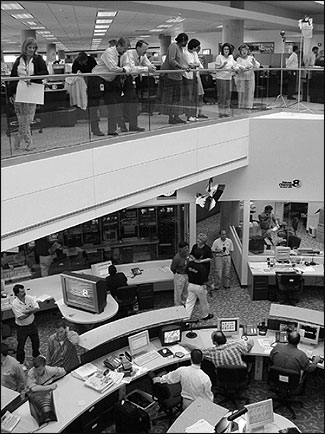

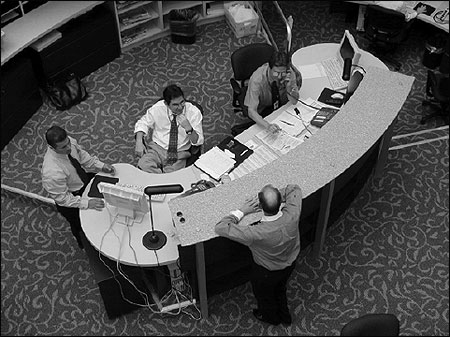

At our NewsCenter, built to facilitate this kind of convergence, a multimedia desk is the pulse of this brave new world. Editors from The Tampa Tribune , WFLA-TV, Tampa Bay Online (TBO.com), and our Archive & Research Center sit side by side, allowing them to make quick decisions about how best to share coverage of breaking news. When a massive fire broke out in our downtown entertainment district, Tribune reporters at the scene phoned in commentary as WFLA went live with the story. In turn, WFLA video was fed to TBO.com. An Internet editor helped gather additional information online that provided depth for the Tribune’s stories. An A & R researcher combed years of clips to provide new angles as each medium’s deadline approached. [A WFLA reporter writes about her experience filing stories across these various media on page 52.] The notion of newspaper reporters working regularly with “those shallow people” in TV news or TV reporters working with “those boring people” in the press would have been unthinkable even 10 years ago. Now it’s happening here, and it’s the wave of the future everywhere, as different media learn to recognize and leverage each other’s strengths to create greater value for the customer.

For the print journalist, this means learning new skills (talking to a camera), new language (voice-overs and interrupt-for-broadcast earpieces), and making decisions based on how customers need information rather than on when the presses next roll. TV journalists face similar challenges as they, too, learn a new language (pagination, maestro sessions, ledes), and as they write for a medium in which words are more important than images.

Those who work in isolation in the 21st century will fail, whether it is news organizations or individual journalists. So, too, will those who ignore the need to master a wider range of tools. No longer are typewriters, notepads and tape recorders enough. Journalists need to know how to use pagination workstations, spreadsheet and database software for computer-assisted reporting, mapping programs for graphic packages and tools needed to partner with TV, radio and the Internet.

Where will newspapers find this new kind of journalist? Can they afford this multi-dimensional talent? Will they be able to keep this new breed once they find it? These are tough questions for publishers, editors and recruiters.

Many observers believe newspapers have to do some changing of their own before expecting to attract or keep the ideal journalist of the 21st century. First and foremost, newspapers must become innovators themselves. Historically, the newsroom culture has been downright cynical about change. “Most organizations are not willing to take a risk,” says Karen Dunlap, the dean at the Poynter Institute. “They’re not willing to applaud the effort. If it fails a little bit, there’s a much greater inclination to say, ‘What the hell was that?,’ the cynical remarks, the critical remarks.”

In other words, the very arrogance that alienates readers alienates the true innovators in newsrooms. “Almost every newspaper employee has seen some poor soul tentatively throw out an idea and have it ripped to shreds,” says Sharyn Wizda, features editor at the Austin American-Statesman. “The attempt to do something different is rarely rewarded on its own if the end result isn’t a blockbuster; because folks are too busy pointing out what went wrong.”

This general lack of respect for people explains a lot of what is wrong with newspapers, according to trainer and consultant Beverly Kaye, coauthor of the new book “Love ’Em or Lose ’Em: Getting Good People to Stay.” “It is a ‘buyer’s market’ where the best journalists have their pick of where to go,” Kaye says. “And you know, what people are asking for is really so simple. They’re saying, ‘Recognize me. Praise me. Ask me what I want to do.’”

Newspapers also must make greater strides in providing training for their journalists. This not only is key to attracting the best professionals; it’s essential to keeping them. And it’s essential to creating the kind of journalism that today’s Americans want and expect. “If newspapers think they do enough training, we are completely out of touch,” says Bill Ostendorf, managing editor of visuals at the Providence Journal. “Editors have discovered this is part of the credibility problem.” Errors occur because reporters know too little about the subjects they cover. More than half of journalists received fewer than 20 hours a year of training, according to a 1998 study by The Poynter Institute.

Salaries are a problem as well, especially if newspapers want to attract an even more sophisticated brand of journalist. The pay for reporters and editors is on par with nurses, high school teachers, firefighters and telephone line installers, according to the September issue of American Journalism Review (AJR). It doesn’t come close to that of lawyers, engineers, airline pilots, and other professional groups. Gains made in previous years have slowed. Experienced newspaper reporters averaged two percent increases this year, “the worst raises have been in at least five years,” according to AJR.

Compensation will become particularly tricky in a converged world. When a newspaper reporter covers a story for TV and online as well, should they be paid more than those who work in only one medium? Different models are being explored at this stage. The most common arrangement, and the one we use at the Tribune, is this: Convergence duties are considered part of the job, but no one is expected to work longer hours. If a reporter files a report to Tampa Bay Online, participates in a two-minute talk-back with an anchor during a WFLA broadcast, and then writes a story for the next day’s Tribune, they simply spend less time on the newspaper that day, perhaps postponing work on another story.

The trickiest questions may arise with photographers. Tribune photographers are beginning to carry video cameras, and by next year WFLA photographers will use digital cameras. So they will be producing images for each other’s organization and for TBO.com. Pay and perks for those two groups are different at this point. Will there need to be some changes? Probably.

One last issue: The larger the newspaper, the greater the likelihood that a majority of its journalists come from out of state. To get the best they can afford, newspapers recruit nationally. That makes bonding with the community a daunting task for journalists. In an era when connecting with readers is more important than ever, newspapers must devise ways to help new hires forge those connections quickly.

The industry need not wait for the April results of its massive reader survey to begin making changes essential to regaining the public’s trust.

- The first target should be newsroom arrogance. Better leadership and more careful hiring is the answer.

- The second target should be newsroom ignorance. Better training is the answer.

- The third target should be the salary structure. It will be next to impossible to hire and keep the kind of journalist needed to reestablish credibility with readers without better pay and better perks.

Patti Breckenridge is assistant managing editor for organizational development at The Tampa Tribune. She headed the Tribune’s online publishing group and, as the paper’s first training and recruiting manager, developed the nation’s largest newsroom training program.