Photo by Alejandra Villa.

Many of my fellow Latino journalists would surely agree that this dual identity—being a journalist and being Latino—is a double-edged sword. And many of us, seeking to establish independence from ethnic identification, use a common defense to create a boundary: I’m not a Latino journalist, I’m a journalist who happens to be Latino.

Oh, that it could be so.

In my 14 years as a print journalist (and, several years prior, working in broadcast journalism), it has been impossible to separate my ethnicity from my profession. Some of this forced coupling comes from a journalistic community that is eager to find reporters and editors who can provide insight into the nation’s fastest-growing ethnic group. Some of it comes from an ethnic community—historically underserved by mainstream media—that expects those who are Latino to use their position to advance its agenda.

But I have learned not to fret about this duality and to accept that it comes with the territory of my chosen profession. And the fact is, if you’re a good enough journalist you can control the situation, and the double-edged sword can be used to your advantage. It’s happened this way for me.

In 1987, I was heading a nonprofit media arts center in my hometown of San Antonio, Texas. The arts editor at the Hearst-owned San Antonio Light newspaper called to ask if I’d be interested in doing freelance writing. He wanted me to focus on Latino theater and literature. Much to his surprise I turned him down, letting him know that I did not want to be pigeonholed. He asked what would interest me, and I suggested writing a wide-ranging, weekly arts column. He accepted.

Because I was working in a city in which at least half the population was Mexican American, the column was naturally inclusive of that (dare I say, my) community. And yet I retained the freedom to write about subjects where ethnicity or race did not play a role.

It was in this job that I first felt nicks of the double-edged sword: I was initially embraced by a Chicano arts community that had never enjoyed a critical voice representing its interests in the newspaper, and I was criticized by white readers—who comprised the majority of the paper’s subscribers—for seemingly being an ethnic apologist. Attitudes changed when I wrote columns that were critical of some Chicano arts institutions and leaders. Then it was my community’s turn to wonder whose “side” I was on.

The freelance column led to a staff job as an arts/entertainment reporter, from which I was promoted to arts editor. In 1989, I was hired as arts editor of the Los Angeles Times edition in San Diego. I didn’t write a column in San Diego, but I reviewed both the visual and performing arts events. One review in particular exemplifies the duality of being an ethnic journalist: An African-American husband/wife team of theater artists brought their show to town. They were talented, seasoned performers, but I found some of their material predictable and unoriginal. I wrote this in my review.

Some months later, I had a conversation with an acquaintance who worked at a government arts agency. He told me that my review had caused some rumblings. Chuckling, he said something to the effect of, “Man, you were tough on them.” The implication was that it was rare, if not unheard of, for a journalist of color to be critical of artists of color. That kind of response to my review simply speaks to the paucity of ethnic journalists who are cultural critics. (More on that later.) Look at it this way: When was the last time a white critic was told, “Man, you were tough on those white artists?”

In the spring of 1990, I came to Los Angeles as an assistant editor in Calendar—the Times’s arts and entertainment section. Here, all these issues related to being a Latino journalist have crystallized. While not my home, this city feels familiar. In many ways Los Angeles is San Antonio writ large—very large. Both have huge Mexican-American populations whose history dates to the founding and development of the cities. The Latino communities in both cities include a massive underclass that is plagued by social and economic problems. But both communities have made significant political strides: Los Angeles is just now on the verge of electing its first Mexican-American mayor in modern times—20 years after Henry Cisneros was first elected mayor of San Antonio.

Like San Antonio, Los Angeles has a large and talented community of creative Latinos working in the arts and entertainment fields. As in San Antonio, Latinos here had been largely unaccustomed to having one of their own working in the newspaper section devoted to cultural coverage.

Just after my arrival here, one of those arts organizations hosted a reception to introduce me to its largely minority constituency. While I was originally uncomfortable at accepting the invitation, I decided it was an opportunity to meet a lot of people in one setting. In my comments that day, I employed the traditional defense: “I’m not a Latino journalist; I’m a journalist who happens to be….”

…Yada, yada, yada. At least that’s what it seemed the audience heard, because I was soon receiving calls from reception attendees who had expected to receive preferential treatment from me. And it continues to occur to this day. It’s unsettling when another person of color plays the intercultural equivalent of the race card. But, as I’ve gently but firmly explained the facts of journalism, I’ve also come to understand the debilitating power of under-representation.

It’s a stark condition that came to light during the charged debates about multiculturalism during the 1990’s. Working in the cultural arena, I came to view multiculturalism as communities of color seeking empowerment to define themselves and the terms under which their creative work would be critically encountered. That, of course, flew in the face of the Euro-centric values that have defined cultural criticism in this country.

This has, on occasion, become a contentious issue at the Times which, as far as I know, has never employed a staff critic who wasn’t white. (And very few of them have been women.) A few years ago, I almost resigned over a review of a Chicano art show written by a freelance critic who had filed what I thought was an uninformed, inflammatory piece of criticism. My threat wasn’t idle, but I decided to stay after my supervisor ordered a rewrite that had to meet my approval. Again, this incident speaks to the small number of journalists of color who choose cultural journalism as a career path. In a city like Los Angeles—home to large and growing Latino, black and Asian communities—this is a situation that can’t continue indefinitely. I would never argue that work by artists of color can only be reviewed by critics who share a common ethnicity. But at the Times, critics are in the position of approaching culturally specific work as outsiders. A different approach would be healthy and refreshing.

My 12-year tenure at the Times has been spent in Calendar, where I am now editor of the five-days-a-week section. (Other editors oversee the Sunday and Thursday/Weekend Calendar sections.) I also help supervise the department’s reporters who were hired as part of the Times’s Latino Initiative, launched in 1998 to increase and improve the newspaper’s coverage of Latino issues and communities.

Originally, the three reporters we hired were responsible for beats including television, radio, film, pop music, and fine arts. Not surprisingly, each of them has encountered the double-edged sword of being a Latino journalist. But each has persevered and earned the respect of the Latino community by being fair and evenhanded. And while they are all primarily beat reporters, we have encouraged their efforts to write occasional commentaries and opinion pieces that use their ethnic backgrounds as a filter. It’s a small but significant step in this paper’s progress towards repairing an historically adversarial relationship with the Latino community.

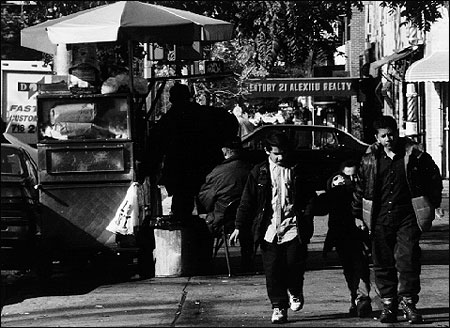

Photo by Vanessa López.

Oscar Garza edits the Los Angeles Times daily Calendar section.