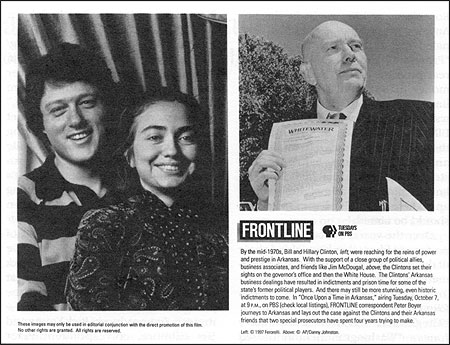

Images from “Frontline’s” Whitewater program.

Twenty years ago, a South African charmer named David Fanning and I were sizing each other up in a bar at the Century Plaza in Los Angeles. He was putting together a weekly PBS documentary television series, and I was trying to parlay a freshly minted Nieman year into some kind of honest work that didn’t involve cranking out news pieces, or those things they call “segments” on so-called “newsmagazine” shows.

Fanning’s vision was infectious and, as it always has, matched my enthusiasm. He was promising a weekly, one-hour public affairs documentary presence on PBS unfettered by the usual death knell to ideas on Public Broadcasting: political deals between stations, independent producers, and other constituency-driven groups.

The series would be produced by the legendary Boston PBS station, WGBH—but Fanning’s new idea was that the station would act more as a publishing house for independently produced programs (“authored works,” as he put it). The individual programs would be made, said Fanning, by the best producers he could find, wherever they lived and worked. I lived and worked in Seattle.

Then, the big finish: We weren’t, he whispered, going to succumb to that other TV beast—the 800-pound gorilla known as the face-time-demanding-on-air-correspondent.

“A producer’s series,” he said with satisfaction.

That did it, he had me. I was on my way back to Boston.

During the next 20 years, David and I (and dozens of producers) have made nearly 400 “Frontline” documentaries. It’s been a wild ride.

I signed on as senior producer for the first seven seasons (Michael Sullivan ably followed me and is now putting together PBS’s ambitious new magazine program). As those of us present for the creation of “Frontline” steered (some would say veered) among the remarkably complicated choices involved in inventing a new kind of television, the series began to take on a life and style of journalism all its own—slightly edgy, iconoclastic, politically perverse, and frequently surprising.

Of course, this business of inventing a new kind of TV show had its own peculiar learning curve. First there was the issue of picking the stories. The hundreds of aspirants that inundated us wondered when our “RFP” was going out. We didn’t know what an RFP was. (A “Request for Proposals,” our grant-writing friends taught us.)

“Back of an envelope,” was the way David described the way we worked out our best film ideas. But try telling that to a producer who had spent years preparing 20-page treatments for the labyrinth formerly known as “PBS/Corporation for Public Broadcasting funding committees.”

Then, of course, there was the daunting task of finding just the right producers. Louis Wiley, our founding series editor (and the ongoing conscience of the broadcast), wrote a paragraph that became our working definition of a “Frontline” producer: “We seek a proven track record with long-form documentaries; a willingness to work under the editorial direction of an executive producer, and a journalistic sense of fairness.” The last two criteria were designed to publicly define us as a fundamentally journalistic institution and to define the difference between our producers and that other thoroughly worthy but undeniably different group of “independent documentary” producers (with an emphasis on the word independent).

We found some of our first colleagues languishing at the moribund “CBS Reports” and “ABC News Closeup” units. Others came from the BBC and that newly invented pool, downsized producers from local stations that were going out of the serious television journalism business (Westinghouse, for example). Bill Moyers had trained some, and so had WGBH.

Then, of course, there was the problem of getting an audience. For that, PBS and our board of directors clamored for a star—that 800-pound gorilla David so proudly eschewed during that first meeting in Los Angeles. After six months of kicking and screaming (and interviewing some very difficult people), we took the plunge and, in typical early “Frontline” style, we went all the way—and, in NBC News anchor/star Jessica Savitch, we got Godzilla and Fay Wray. As difficult as Jessica often was, we came to believe in her role as a kind of marquee figure and, when Judy Woodruff signed on after Jessica’s death, that role actually grew to include a thoroughly legitimate journalistic function.

Armed with the anchor, the producers, those back-of-an-envelope ideas, and our own early 30-year-old enthusiasms, we then set about creating (and defining for ourselves and the producers) exactly what a “Frontline” documentary was.

It was, as Wiley said, “designed to help the citizen perform his or her civic duties,” but it was decidedly not one of those occasionally boring network “white papers,” as they had come to be called. It was investigative, but not a piece of advocacy; stylized but not overdone (we had lots of rules about music and re-creation). The truth is, in the early going, we weren’t sure what a “Frontline” was—but we figured we’d recognize it when we saw it and, of course, after a while, we did.

We lit the rocket with “The Unauthorized History of the NFL.” That program’s back-of-an-envelope description read: “The mob influenced the outcome of at least one Superbowl and L.A. Rams owner Carroll Rosenbloom was murdered as part of it.” The program was a blockbuster premier and immediately put “Frontline” on the map. The program got the highest ratings of any public affairs documentary in the history of PBS.

But just as we rode the rocket up, we also rode it down. In that tension between good filmmaking and good journalism, many believed the filmmaking (some of it artful but sensational) got the best of the journalism. The program was savaged by TV critics, sports fans, and many journalists. The highly respected television critic of the Los Angeles Times, Howard Rosenberg, said the program was sufficiently flawed to bring into question the continued existence of the series itself.

Then, the very next week, we redeemed ourselves with “88 Seconds in Greensboro,” a dark southern tale about the Ku Klux Klan and a shootout with some communist party members in Greensboro, North Carolina. Rosenberg, writing again in the Los Angeles Times, said perhaps he’d signaled the death knell too early for “Frontline,” and that this film showed real promise for the series. For our money, in “88 Seconds” the real “Frontline” had emerged. Both films, by the way, were produced and directed by Bill Cran (CBC, BBC). In “Greensboro,” the writer Jim Reston’s spare narration and Bill’s instinct for narrative storytelling neatly matched. Now we knew what a “Frontline” looked like and where our journalistic aspirations should be aimed.

Over the years, the combination of writer and filmmaker has yielded some of the most powerful “Frontline” documentaries: Richard Ben Cramer and Tom Lennon’s biographies of Bill Clinton and President George Bush, “The Choice;” Bill Greider and Sherry Jones’s “Washington Behind Closed Doors,” and their series on democracy. Peter J. Boyer and I have collaborated on a dozen stories ranging from Waco to Whitewater; Reston, Cramer, Grieder and Boyer appeared in the films—but they were hardly correspondents in the classic network model. Their contributions were intellectual, structural and collaborative. True to Fanning’s original promise, the producers have always been the leaders of the teams, and the task of blending narrative, structure and content has always been our province. And, perhaps most importantly, those relationships have been developed personally, not imposed institutionally.

During these years, other models for classic “Frontlines” have emerged: Ofra Bikel’s extensive body of work, including her stunning investigation of the allegations of child abuse in Edenton, North Carolina; Mark Obenhaus’s trilogy about life in Chester, Pennsylvania, including the riveting “Abortion Clinic,” and David Sutherland’s epic six-hour mini-series, “The Farmer’s Wife.” “Frontline” has also thrived on the investigative work of producers like Lowell Bergman and Marty Smith and the quirky films of Marian Marzynski. In every one of these programs, the competing demands of filmmaking and journalism have been the central challenge.

Itching to try my hand at producing/ directing and writing my own “Frontlines,” I left the senior producer job in 1987. Since then I’ve made more than 30 documentaries for “Frontline,” each and every time struggling to get the balance between good filmmaking and good journalism just right. While every experienced “Frontline” producer has his or her own method (that’s part of the beauty of what Fanning created), I have some rules of my own particular road.

I live and breathe in the world of character-driven narrative. I also love chasing a story everybody in the pack thinks is dead and buried. If it has great characters and a story arc—and if the journalism circus has come and gone—my team (co-producers Rick Young and Jim Gilmore, correspondent Peter Boyer) and I turn the gravestone over and look for the things everybody missed: The Branch Davidian siege in Waco, Texas, turned out to be at least partly about an internal struggle within the FBI; Whitewater wasn’t just about “a failed land deal” but also about a successful one named Castle Grande (speaking of character-driven narratives!); The Chief of Naval Operations Mike Borda’s suicide wasn’t just about some bogus medals of valor but about the struggle between men and women at the pinnacle of the Navy’s all-male culture—the fighter pilots; the so-called largest police corruption scandal in the history of Los Angeles, Rampart, was really about a supercharged racial climate and a very slick misdirection by a cop and his buddies nabbed in a cocaine bust. The list goes on.

There are, naturally, limitations to the method. While we unearth documents, new footage, and fresh insights, I’m not really in the business of trying to make or especially break news (that’s for my colleagues Marty Smith and Lowell Bergman). Because the stories aren’t happening at the same time as I’m shooting them, the cinéma vérité style (the stunning access of filmmakers on the spot) isn’t, as they say, in my toolbox. So I’ve developed a skill rarely talked about in so-called serious discussions about broadcast journalism: I actually direct my films. I think about image systems, lighting, scene setting, mood and music.

When I can, I employ the devices, film grammar, and time-honored structural sense of Hollywood movies. I know that sentence shocks my more sober colleagues, and it’s often the cause of spirited debates inside “Frontline,” but the truth is, in order to tell my stories, I’m pushing the boundaries—and challenging the conventions of straight-up-and-down documentaries. So in that “Frontline” struggle between style and substance, I find myself paying attention to the filmmaking as much as to the journalism.

In the two decades that I’ve spent trying to hone the craft, I am most proud of the films that raise questions, inspire debate, and sometimes even change policy. Critics don’t always like the films, but audiences seem to—they are consistently among the highest rated “Frontlines.” But these aspirations—and outcomes—are not mine alone. As my dear friend and colleague David Fanning and I—after several decades in the business and suitably less naive—now say, this business, if done right, doesn’t get any easier. It gets harder—harder to stay the serious course in a television environment so littered with less. Harder to find the money but, most importantly, harder to satisfy our own quest for the perfect “Frontline.”

“Frontline” has won the Gold Baton and several silver batons from the duPont-Columbia awards, six George Foster Peabody Awards, and dozens of Emmys. Michael Kirk, a 1980 Nieman Fellow, has won his fair share of those awards as a producer/director, as well as two Writers Guild of America Awards. He now serves as a consulting senior producer to “Frontline” and produces two films each season as an independent producer.