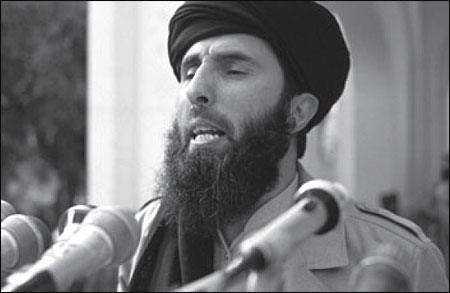

Engineer Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, leader of Hezb-i Islami Afghanistan, addressing a rally. Peshawar, Pakistan. November 1987. Photo by Mohammad Karim.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Revealing Beauty in the Harshness of War"

- RezaLast January, an old Afghan friend called to tell me that Haji Daud, the director of the Afghan Media Resource Center (AMRC) in Peshawar, Pakistan, was trying to find an educational institution in Europe or the United States that would help the center preserve its news archive. Having conducted research on the war in Afghanistan since the early 1980’s, I knew that the AMRC had sent teams of video cameramen, photographers and print journalists inside Afghanistan to cover the war during the last years of the Soviet occupation and the first years of the civil war that followed in the wake of the Soviet withdrawal.

I also knew that the plan for setting up the center had generated considerable controversy back in 1986. The U.S. Information Agency (USIA) at that time had provided a grant to the College of Communication at Boston University to train Afghans in the rudiments of journalism and many, including the dean of the college, had protested what they viewed as an unhealthy co-mingling of government propaganda efforts and newsgathering. Whatever concerns I had about reawakening this controversy quickly faded when I heard from Haji Daud his estimate that the archive contained 3,000 hours of videotape, 100,000 negatives and slides, and 8,000 hours of audiotape.

When I traveled to Peshawar to talk about possibly collaborating to preserve this archive, Daud made it clear that he wanted the original materials to stay in Peshawar. So we brought a portion of the collection to Williams College, along with AMRC staff who would be trained in photo scanning, video digitization and editing, database management, and other techniques needed for managing the archive. The digital copies we produced will stay at Williams, which will serve as the permanent repository for the material. The originals will remain in Pakistan in the hope that eventually they can go to Kabul when the political situation allows. Plans are also being formulated so the archive can be made available to the public through museum exhibitions, online photographic and video databases, and one or more books and documentaries.

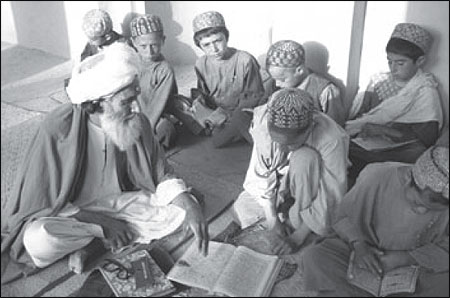

As an anthropologist, what I find most intriguing is the view the archive provides of Afghan society as it adapted to war, particularly the role of Islamic political parties in remolding Afghan culture according to their moral precepts. The AMRC collection is far more revealing than comparable material produced by Western cameramen, most of whom were skilled technicians and courageous in their pursuit of news, but few of whom had much grasp of what was going on around them.

During the late 1980’s, journalists risked the dangers and hardships of an extended trip inside Afghanistan because of the possibility of returning with images of Soviets fighting in a guerrilla war with the Afghan mujahedeen. “Bang-bang” footage was the prize and, in truth, Western journalists were ill-equipped to capture much else, since they didn’t speak the local languages or know much about the society. Afghan cameramen could converse with people and understood the dynamics of the culture, so when a ritual took place, or a religious leader spoke to his people, or a dispute broke out, AMRC cameramen were able to follow the action and interview the principals. This archive of their work consequently resembles something like an anthropologist’s field notes that collectively provides a three-dimensional picture of life in a time of war and of war as a way of life.

The AMRC archive is valuable as well for what it tells us of the politicization of journalism and the role of news in a time of partisan struggle. It was created by the U.S. government to ensure that the story of the Soviet Union’s difficulties in Afghanistan would be seen by the world. But that was only one part of the political equation. In the highly charged environment of Peshawar, the AMRC was able to operate only if it recruited its trainees directly from the Afghan resistance parties. As a result, while the professors from Boston University were intent upon teaching their students the principles and practices of “objective” news gathering, the “journalists” at AMRC were deeply implicated in the political struggles and agendas of their political leaders and parties. At the same time, there was also pressure brought to bear by the media outlets themselves for the AMRC cameramen to come up with combat footage that they could broadcast to the world, and this also produced a sometimes corrosive effect on the truth.

Though many journalists associated with the center took their obligation to objective journalism seriously and endeavored at great risk to report on the conflict in Afghanistan as honestly as they could, some in the West came to view the news coming out of the center as compromised. However, what made for problematic journalism makes for great history. Aside from the record it provides of the two decades-long struggle in Afghanistan, the AMRC is itself one piece of the story of the war, and the events of this fall have made understanding that story more important than ever.

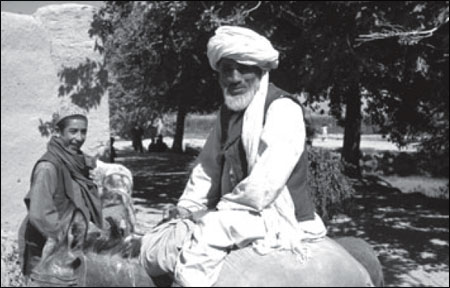

Old man on a donkey, Kandahar Province. June 1987. Photo by Mohammad Karim.

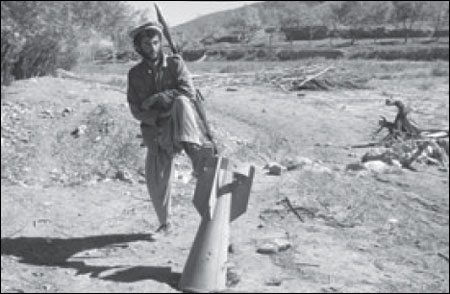

Mujahed with unexploded Soviet bomb, Logar Province. November 1987. Photo by Hafiz Ashna.

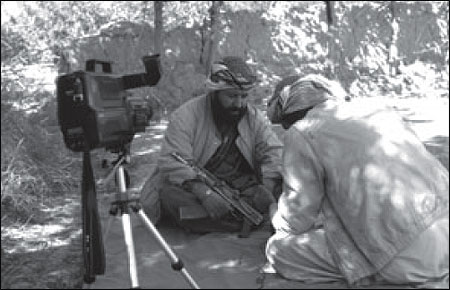

Commander Aliadin being interviewed by AMRC cameraman, Mazar-i-Sharif Province. January 1988. Photo by Baz Mohammad.

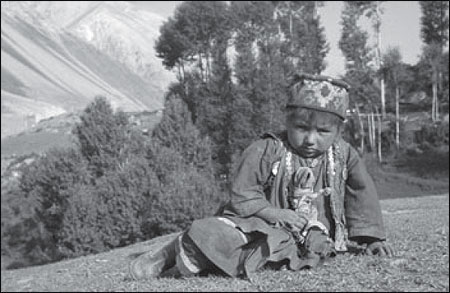

Little girl on a hillside, Kunduz Province. December 1990. Photo by Fazil Haq.

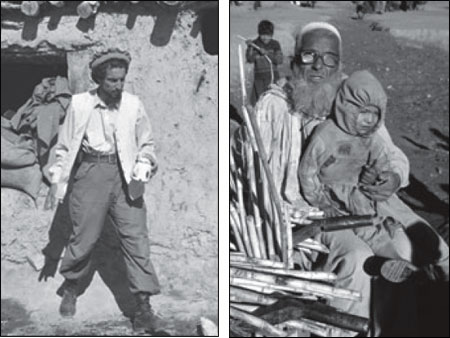

At left, Ahmed Shah Massoud in Takhar Province. 1990. Photo by Ahmad Shah. At right, an old refugee selling sugar cane with a child in his lap. Peshawar, Pakistan. October 1990. Photo by Mohammad Hashim.

Mulla teaching students, Kandahar Province. November 1990. Photo by Mohammad Muqim.

David B. Edwards is a professor of anthropology at Williams College and the author of “Before Taliban: Genealogies of the Afghan Jihad” (University of California Press, Spring 2002).