On the day that the Iranian-American journalist Roxana Saberi, charged with espionage by Tehran, was handed her eight-year sentence, I received several dozen messages asking if I planned to write something about the case. It is a natural question for those who know me: I am Iranian. I write about Iran, and I often write what in journalism we refer to as human-interest stories. Yet as certain as I was about Saberi’s innocence, I refused to write only about her. That would be precisely what Tehran’s ruling puppeteers wanted everyone to do. And I am, above all, a writer, not a marionette.

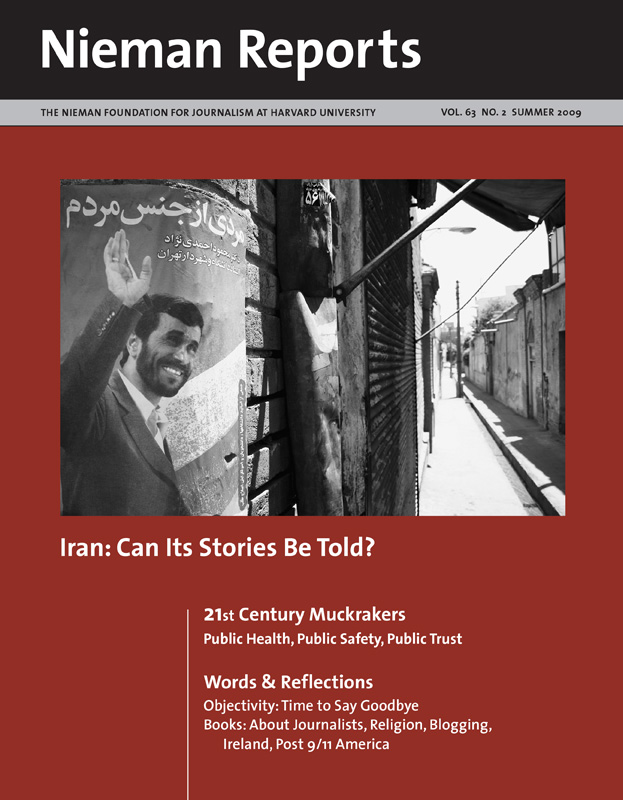

I am also an American. I believe in our goodness and in our genuine desire to learn the truth. I reject my Iranian compatriots’ conspiratorial views about Big Brother’s hold on our media. Yet I cannot quite explain why the coverage of Iran in our press is so profoundly inadequate. Every week, so many hundreds of articles are written about Iran’s nuclear program that yellow cake now has the appeal of pastry to our palette, and its top chef, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, is watched just as avidly. Espionage is cheap in Iran, and hundreds are charged with it every year, but few “spies” become household names. With Iran’s presidential election only weeks away, as I write this, I hardly call it a coincidence.

Events Overshadow Stories

Tyrannies are born in crisis. They thrive on crisis. Iran is no different. From its inception, the regime understood the value of a grand spectacle, and it has staged and exploited many ever since.

On November 4, 1979, the day the American embassy in Tehran was seized, the world’s attention became solely focused on the fate of the 52 American hostages thereafter. That Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan, in protesting the takeover, resigned and his highly liberal cabinet collapsed was scarcely captured by the foreign lenses. Neither were the subsequent execution of the foreign minister, Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, and the arrest of the government spokesman, Abbas Amir-Entezam, on the charges of espionage for the United States, a pattern that, astonishingly, still continues, as does Amir-Entezm’s detention.

The American hostages suffered greatly, yet were released after 444 days. But Iran’s political landscape was never the same in the aftermath of the takeover. While the world was consumed by the captive Americans, the hardliners in Iran, ceasing upon the global oblivion, obliterated the opposition—exiled, imprisoned and executed them—and implemented the repressive laws, including the Islamic dress code for women, which they had not been able to pass in the early months after the 1979 revolution.

Then came another leviathan crisis: the war with Iraq. Four years into the ordeal, when Saddam’s bombs had reached Tehran, I was standing on queue to receive our monthly allotment of eggs and other staples from the local mosque, when a neighbor complained of the shortages and the incessant shriek of sirens. A Revolutionary Guard member barked at him with a rejoinder, not unlike what the neocons used against those critical of the Patriotic Act: It was unpatriotic, even un-Islamic, to complain when the country was at war.

With eyes averted to the war, droves of political prisoners were executed, even against the advice of the country’s second greatest clergyman, Ayatollah Montazeri. By August 1988, several thousand prisoners, even some who had nearly served their terms and were on the brink of release, were killed in the span of days. Montazeri had pleaded with the authorities to at least wait until after the holy month of Moharram had passed. But he was told that too many preparations had been put in place to stop the bloodshed. Because of his vehement objections, Montazeri, once in line to replace Ayatollah Khomeini as the supreme leader, has ever since been banished to his quarters in Qom, Iran.

The mass, nameless grave, where the relatives of the dead gather every September to remember their loved ones, is called Khavaran, a corner of Tehran’s main cemetery that the officials have dubbed “the Damnedville.” The thousands who lie there never made it to the headlines that August because in July, the USS Vincennes shot down an Iranian Airbus killing 290 passengers and crew aboard. Oblivion reigned once more, and the executioners ruled.

After the end of the Iran-Iraq war in late 1988, there was a new sensation. Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses took center stage, and the author singularly commanded the thousands of headlines that the dead never did. The word “fatwa” entered the popular lexicon. It was just the kind of drama the regime has always cherished: The West was riled up, and the dispossessed in the Muslim world, to whom Iran increasingly appeared as pioneering their cause, were electrified. Ironically, it was the fair-minded Rushdie himself who began to speak on behalf of those dead and all the other tales that were going unreported.

Absence of Good Reporting

I revisit this history, in part, because it is ongoing but more importantly because it has far greater implications than we realize. Poor reporting from and about Iran has kept the West in the dark. In this lightlessness, Iranians are rendered as ghosts. Yet it is not for altruism, the mere defense of a people’s dignity, that we must change our ways of telling the news of Iran. Rather, it is the ubiquitous encroachment of that darkness, even upon our leaders, that makes it an essential mandate, a point that veteran foreign policymakers, such as Richard N. Haass and Martin S. Indyk, formulate in this way: “The United States simply lacks the knowledge and the guile to [influence] Iran effectively.”

Diplomats are human. They, too, must gather information in much the same way as the rest of us, only they have the disadvantage of having access to dubious sources such as the CIA. They, too, often rely on reporters. The absence of good reporting is one reason why Iran remains an enigma for the elite and ordinary readers alike.

That is not all. Our inadequate reporting is also, in part, the reason for the inexplicable stagnation in Iran’s reform movement. Iranians know that the outlandish rhetoric of their unpopular leaders capture the imaginations far more than the tales of their resistance against those leaders. When Iran’s President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad proposes to hold a Holocaust cartoon exhibit, thousands of headlines report his intentions. But when the exhibit goes on and its halls go unfrequented, scant items tell of the nation’s bottomless disinterest in their president’s follies. When he speaks against Israel, the world stands at attention. But when he arrests journalists, writers and intellectuals who criticize their own government for diverting much needed funds at home to Hamas and Hizbullah, the lede, if written at all, is buried in a footnote.

In February 2006, when there seemed to be nothing but outrage against the Danish cartoons coming out of the Middle East, a bus strike as significant as Montgomery, Alabama’s bus boycott brought Tehran to a standstill. Hundreds of drivers refused to work, and idle buses lined the terminals as far as the eye could see. But the only images that appeared on the evening news in the West were those of a handful of hoodlums protesting in front of Denmark’s embassy, throwing stones and smirking for the cameras.

Conscientious Americans always rant about the apathy of their fellow Americans. Iranians of all stripes always speak of despair among their people. Apathy and despair are among the offspring of oblivion. The hundreds of teenage girls and young women who stormed the Haft-e-Tir Square in Tehran in June 2006 to demand an end to gender apartheid in their country in a movement that has come to be known as the “One Million Signature Campaign” might as well have stayed home and killed their every hope because their presence, their subsequent arrests and imprisonment, went unrecorded. It was not reported in the American media until 2009.

Three years is an eternity for a 20-year-old to know that others are not deaf to her, to keep herself from wondering if she is not mute, or if her existence matters.

Roya Hakakian is the author of “Journey From the Land of No: A Girlhood Caught in Revolutionary Iran,” her memoir of growing up as a Jewish teenager in postrevolutionary Iran, published by Crown in 2004. She received a 2008 Guggenheim fellowship in nonfiction.

I am also an American. I believe in our goodness and in our genuine desire to learn the truth. I reject my Iranian compatriots’ conspiratorial views about Big Brother’s hold on our media. Yet I cannot quite explain why the coverage of Iran in our press is so profoundly inadequate. Every week, so many hundreds of articles are written about Iran’s nuclear program that yellow cake now has the appeal of pastry to our palette, and its top chef, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, is watched just as avidly. Espionage is cheap in Iran, and hundreds are charged with it every year, but few “spies” become household names. With Iran’s presidential election only weeks away, as I write this, I hardly call it a coincidence.

Events Overshadow Stories

Tyrannies are born in crisis. They thrive on crisis. Iran is no different. From its inception, the regime understood the value of a grand spectacle, and it has staged and exploited many ever since.

On November 4, 1979, the day the American embassy in Tehran was seized, the world’s attention became solely focused on the fate of the 52 American hostages thereafter. That Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan, in protesting the takeover, resigned and his highly liberal cabinet collapsed was scarcely captured by the foreign lenses. Neither were the subsequent execution of the foreign minister, Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, and the arrest of the government spokesman, Abbas Amir-Entezam, on the charges of espionage for the United States, a pattern that, astonishingly, still continues, as does Amir-Entezm’s detention.

The American hostages suffered greatly, yet were released after 444 days. But Iran’s political landscape was never the same in the aftermath of the takeover. While the world was consumed by the captive Americans, the hardliners in Iran, ceasing upon the global oblivion, obliterated the opposition—exiled, imprisoned and executed them—and implemented the repressive laws, including the Islamic dress code for women, which they had not been able to pass in the early months after the 1979 revolution.

Then came another leviathan crisis: the war with Iraq. Four years into the ordeal, when Saddam’s bombs had reached Tehran, I was standing on queue to receive our monthly allotment of eggs and other staples from the local mosque, when a neighbor complained of the shortages and the incessant shriek of sirens. A Revolutionary Guard member barked at him with a rejoinder, not unlike what the neocons used against those critical of the Patriotic Act: It was unpatriotic, even un-Islamic, to complain when the country was at war.

With eyes averted to the war, droves of political prisoners were executed, even against the advice of the country’s second greatest clergyman, Ayatollah Montazeri. By August 1988, several thousand prisoners, even some who had nearly served their terms and were on the brink of release, were killed in the span of days. Montazeri had pleaded with the authorities to at least wait until after the holy month of Moharram had passed. But he was told that too many preparations had been put in place to stop the bloodshed. Because of his vehement objections, Montazeri, once in line to replace Ayatollah Khomeini as the supreme leader, has ever since been banished to his quarters in Qom, Iran.

The mass, nameless grave, where the relatives of the dead gather every September to remember their loved ones, is called Khavaran, a corner of Tehran’s main cemetery that the officials have dubbed “the Damnedville.” The thousands who lie there never made it to the headlines that August because in July, the USS Vincennes shot down an Iranian Airbus killing 290 passengers and crew aboard. Oblivion reigned once more, and the executioners ruled.

After the end of the Iran-Iraq war in late 1988, there was a new sensation. Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses took center stage, and the author singularly commanded the thousands of headlines that the dead never did. The word “fatwa” entered the popular lexicon. It was just the kind of drama the regime has always cherished: The West was riled up, and the dispossessed in the Muslim world, to whom Iran increasingly appeared as pioneering their cause, were electrified. Ironically, it was the fair-minded Rushdie himself who began to speak on behalf of those dead and all the other tales that were going unreported.

Absence of Good Reporting

I revisit this history, in part, because it is ongoing but more importantly because it has far greater implications than we realize. Poor reporting from and about Iran has kept the West in the dark. In this lightlessness, Iranians are rendered as ghosts. Yet it is not for altruism, the mere defense of a people’s dignity, that we must change our ways of telling the news of Iran. Rather, it is the ubiquitous encroachment of that darkness, even upon our leaders, that makes it an essential mandate, a point that veteran foreign policymakers, such as Richard N. Haass and Martin S. Indyk, formulate in this way: “The United States simply lacks the knowledge and the guile to [influence] Iran effectively.”

Diplomats are human. They, too, must gather information in much the same way as the rest of us, only they have the disadvantage of having access to dubious sources such as the CIA. They, too, often rely on reporters. The absence of good reporting is one reason why Iran remains an enigma for the elite and ordinary readers alike.

That is not all. Our inadequate reporting is also, in part, the reason for the inexplicable stagnation in Iran’s reform movement. Iranians know that the outlandish rhetoric of their unpopular leaders capture the imaginations far more than the tales of their resistance against those leaders. When Iran’s President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad proposes to hold a Holocaust cartoon exhibit, thousands of headlines report his intentions. But when the exhibit goes on and its halls go unfrequented, scant items tell of the nation’s bottomless disinterest in their president’s follies. When he speaks against Israel, the world stands at attention. But when he arrests journalists, writers and intellectuals who criticize their own government for diverting much needed funds at home to Hamas and Hizbullah, the lede, if written at all, is buried in a footnote.

In February 2006, when there seemed to be nothing but outrage against the Danish cartoons coming out of the Middle East, a bus strike as significant as Montgomery, Alabama’s bus boycott brought Tehran to a standstill. Hundreds of drivers refused to work, and idle buses lined the terminals as far as the eye could see. But the only images that appeared on the evening news in the West were those of a handful of hoodlums protesting in front of Denmark’s embassy, throwing stones and smirking for the cameras.

Conscientious Americans always rant about the apathy of their fellow Americans. Iranians of all stripes always speak of despair among their people. Apathy and despair are among the offspring of oblivion. The hundreds of teenage girls and young women who stormed the Haft-e-Tir Square in Tehran in June 2006 to demand an end to gender apartheid in their country in a movement that has come to be known as the “One Million Signature Campaign” might as well have stayed home and killed their every hope because their presence, their subsequent arrests and imprisonment, went unrecorded. It was not reported in the American media until 2009.

Three years is an eternity for a 20-year-old to know that others are not deaf to her, to keep herself from wondering if she is not mute, or if her existence matters.

Roya Hakakian is the author of “Journey From the Land of No: A Girlhood Caught in Revolutionary Iran,” her memoir of growing up as a Jewish teenager in postrevolutionary Iran, published by Crown in 2004. She received a 2008 Guggenheim fellowship in nonfiction.