The Nieman Foundation was 51 when Vladimir Voina, a magazine editor from Moscow, arrived as its first Soviet fellow. Voina, who said he had come to the U.S. “to study the other side of the moon,” was a gregarious figure on campus, described in a press release as “a glasnost man before glasnost became the party line.”

Scholars hungry for firsthand accounts of a Soviet Union on the eve of collapse made him the most sought-after member of the 1990 Nieman class. Voina rewarded his audiences with accounts of glasnost’s emerging freedoms, including tolerance for investigative journalism. He quoted a line from a popular Russian comedian that captured the country’s complex political moment: “It’s better to read now than to live because life is horrible but the press is beautiful.”

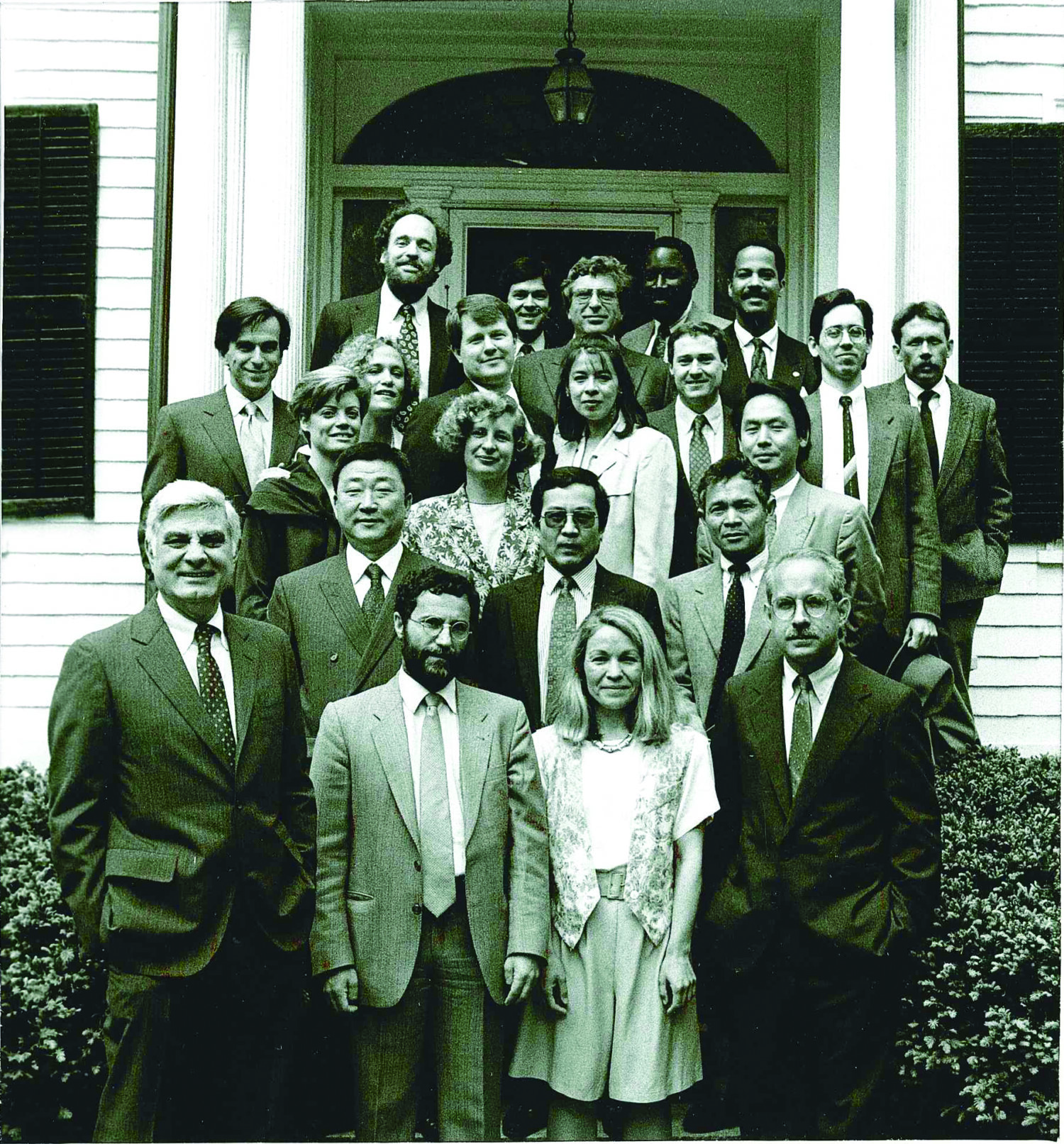

I was a fellow in Voina’s Nieman class, and allowed myself a sort of giddy hope for the future of Russian media. Like most American fellows, I hadn’t known many international journalists until I came to Harvard. But now, after 14 years as Nieman’s curator to nearly 400 journalists from 67 countries, I know many and have learned an enduring lesson about the precarity of hope.

My last four Russian fellows all live in exile, three of them labeled “foreign agents” by the Putin government. Elena Kostyuchenko, this year’s Russian fellow, was covering the full-scale invasion of Ukraine for Novaya Gazeta when her editors were tipped that she was on a Russian military kill list and needed to flee. The editor of the independent Novaya Gazeta, Dmitry Muratov, was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize; the government shut down his newspaper and made it a crime to call a war a war.

No soil, Kostyuchenko says, is immune to the growth of fascism.

“The main thing I want you to know is that it is possible to lose your country. It is possible to lose everything,” she told us. “You know what I was doing three months before the full-scale invasion? Picking out tiles for my bathroom.”

I don’t like to think of Vladimir and Elena as opposing bookends to my Nieman experience. Can’t soil that gives life to authoritarianism be tilled for new crops? Nieman Fellows from Poland report a recent upturn in stability, following the partial defeat of the Law and Justice party’s authoritarian rule. In the Philippines, journalists who endured the violent threats of President Rodrigo Duterte (now facing trial for crimes against humanity) are fighting their way back, owing largely to the courage of Rappler founder Maria Ressa — who won the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize alongside Muratov — and the news site’s editor, 2018 Nieman Fellow Glenda Gloria.

But the trend lines, as seen in my own admittedly limited sample, are undeniable.

Early in my curatorship, I had a discreet list of countries I worried about for my fellows. One spring, following a brazen midday assassination of a prominent Mexican journalist, I pleaded with a fellow to postpone her return to Mexico, one of the world’s most dangerous countries for journalists. But recently there is more to worry about, compelling Reporters Without Borders for the first time in its history to rank the global state of press freedom as a “difficult situation.”

I look at the map and see the faces of my fellows in places like India, Turkey, Hong Kong, Nigeria, Peru, Georgia, Venezuela, Hungary, Israel and more, knowing that increasing government restraints and attacks have put these journalists at risk while choking off news and information. Even countries long hostile to the press have turned up the oppression; for the first time in memory, we have two Nieman Fellows imprisoned, in China and Vietnam, both for conventional journalistic practice.

Perhaps most alarming is the story at home, not words I imagined typing when I began my work at Nieman. The United States, the press index concludes, “is experiencing its first significant and prolonged decline in press freedom in modern history.”

Journalists shot with rubber bullets by law enforcement officials while covering protests in Los Angeles. Journalists banned from the White House press pool for refusing to call the Gulf of Mexico the Gulf of America. Journalists fired in the dismantling of Voice of America, a newsroom dating to World War II. NPR and PBS targeted for defunding. Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos canceling his newspaper’s endorsement of Kamala Harris on the day his aerospace company executives were meeting with then-candidate Donald Trump.

Much has been written, here and elsewhere, about Trump’s war on the press. But the recent complicity of media ownership has been especially chilling. This summer’s $16 million decision by CBS’ parent company to settle a Trump lawsuit over its editing of a “60 Minutes” interview was a bitter pill for its journalists, but so too for those of us who grew up in homes where that Sunday evening viewing ritual was as routine as Sunday Mass.

As we witness these cynical actions, there is a line worth recalling from “How Democracies Die,” by Harvard Professors Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt: We are “vulnerable to the same pathologies that have killed democracy elsewhere.”

A Chinese Nieman Fellow once wrote to me about drawing inspiration from the other fellows. “After I became a Nieman, I had a strong feeling that I’m not a lonely watchdog on the earth.”

What has been most remarkable about the privilege of these 14 years is to behold resilience and collaboration in a community of journalists, something the chilling data about declining press freedom cannot measure. If anything, it is an underused superpower in dark times and I wish our industry more often embraced cooperation over competition in service of survival, something I saw at Nieman every year. This last semester at Harvard has offered a brilliant lesson in what fighting for your future looks like. Such clarity of purpose awaits the whole of journalism too.

There are two memorial trees in Nieman’s Lippmann House gardens. The Eastern redbud was planted in 2017 by the Nieman classmates of Anya Niedringhaus (class of 2007), the Pulitzer Prize-winning AP photographer shot dead by a police officer while covering elections in Afghanistan. It grew outside my office window, and I watched it blossom spectacularly each spring, a specimen as bright and bold as the woman it honors.

I did not want another tree. But when Brent Renaud became the first American killed in the war in Ukraine — shot at a checkpoint while filming a documentary on immigrants — his Nieman classmates procured an Arkansas Black apple in honor of Brent’s home state, and we brought it to Lippmann House in 2023. The species isn’t common in New England, and I worried about the sapling, slight like Brent. Would it even grow in this soil? I tied a ribbon around its tiny trunk to help me locate it that first year.

On one of my final afternoons as Nieman curator, I went to check on the tree, now bearing a crown of leaves, and found two green apples. I yelped, a sound quickly absorbed by the lush June garden.

I sought only proof of life. Instead, the tree is thriving.