- The inside story of a prison murder that took place while guards slept.

- Free, life-saving medicine left on the shelf to expire while government cronies sold their own pricey drugs.

- Heavy thugs with shaved heads attacking journalists.

- A justice system that abuses victims more than punishes offenders.

- Forests on state land cut down with impunity to build cemeteries and mansions for favored officials.

- Women sold into sex slavery and smuggled to Dubayy.

- Earthquake victims who were promised new apartments by the government after their own had crumbled in 1988, but who still live in shacks.

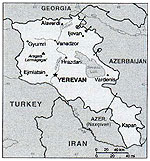

Any investigative reporter would instantly recognize these stories as a rich load of material to mine. Here in the United States we’d be amazed that all of these shocking events are taking place—routinely—in an area the size of Maryland. Yet in Armenia this is only a sampling of the stories pursued by a small number of intrepid, fearless journalists after an investigative training program run by the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) in Washington, D.C. and sponsored by the U.S. Embassy in Yerevan, the capital of Armenia.

Thirteen years after breaking away from the former Soviet Union, Armenian journalists readily tell you that their nation’s press is not free. They confront almost insurmountable obstacles in a society steeped in government, police and legal system corruption.

It would be unrealistic to expect that any month-long program, no matter how ambitious, would result in major changes in work practices or attitudes of journalists. Yet this project to improve investigative reporting techniques for 10 Armenian journalists had a remarkable effect in encouraging them to tackle hard topics and to bring their stories to fruition. This was the most sophisticated and intensive training project I have had the good fortune to be involved with since I began teaching journalists overseas on a Knight International Press Fellowship in 1998.

A Training Journey

Before that fellowship, I had only wistfully fantasized about going over to post-Soviet countries to help build a free press. But in 1997 I had just left a job in Hawaii and had no mortgage or car to support. All my possessions were packed up and put in cold storage, so it was a perfect opportunity to travel and live out some of those fantasies. I asked to be sent to Eastern Europe, and Susan Talalay and the other folks who ran the Knight Fellowship Program granted my wish, assigning me to Hungary, Romania, Slovakia and the Czech Republic for nine months. I taught seminars and workshops ranging in duration from one hour to four months, reaching hundreds of journalists. My accommodations ranged from a cozy furnished apartment in Budapest to a blur of old Communist-built hotels with less than perfect amenities. Hours were long.

I was hooked. The year was transformative and set me on a new career path. While I’m very proud of the work I did as a reporter at The Philadelphia Inquirer for 15 years, I’ve found that this later work as a trainer to be perhaps more meaningful—because of the friends I’ve made, because it reminds me of the soaring purpose of journalism, despite its rooting in nitty-gritty, grinding details, many of which have to be extracted iota by iota, and because it expands my horizon beyond my comfortable life and wakes me up.

Since 1998, I’ve been engaged in training assignments in Kosovo, Bulgaria, Lithuania and Macedonia (I had been slated to do a training session for a local television station there, but it was cancelled when the station was bombed that day by Albanian rebels). These experiences became the foundation for a training manual I wrote for ICFJ, which has since been translated into 18 languages and distributed worldwide.

In 2001, I went to Botswana for four months as the first John McGee International Press Fellow for Southern Africa. (I was followed by Nieman classmate Philip Hilts, who became the second McGee fellow.) Now I work with foreign journalists on a full-time basis, as director of the Humphrey Fellowship Program at the University of Maryland’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism.

Initially I found overseas training too daunting. I’ve watched many trainers give up, finding the country too corrupt to allow for independent publications, or the resources too puny, so that reporters churn out two or three stories a day. But I began to see even the smallest improvements as significant and to realize that results won’t occur overnight. And we trainers have gotten better.

The Armenian Project

Last year’s Armenia project, for instance, was so effective because it was intensive; it lasted over several months and focused on producing high-quality investigative stories. Granted, it was more generously funded than most programs and had the advantage of working with strong local journalists, organized by Edik Baghdasaryan, head of the Armenian Association of Investigative Journalists. His tenacity and bravery in tackling the criminal corruption in Armenia astonished me.

In January 2004, the 10 Armenian journalists were flown to Washington for a week of seminars in American-style reporting. Then each of them, accompanied by a translator when warranted, was dispatched to an outstanding newspaper or television station located in cities around the United States. For two weeks they observed investigative practices, often working alongside reporters at the Richmond Times-Dispatch, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, or KNBC in Los Angeles, among other sites.

My mission was to work with the journalists individually on story projects of their own choosing. While the reporters had promised to send progress reports from Armenia by e-mail to me in the ensuing months, I heard little from them. I feared for the worst. After I arrived in Yerevan in May 2004 and began meeting with them, I found that nearly all had made substantial progress. Some had finished major projects.

Not all 10 of them have completed stories, as of this date. Some suggested that editors at participating news organizations should have been required to publish or broadcast projects or, at the least, have been required to give reporters time off from their regular duties to complete a project, if that was the limiting factor. But I am hesitant to place such demands on any news organization. Investigative reporting is not for everyone. We can’t force people into it. Sometimes the obstacles (lack of time, lack of money, resistant editors) serve to dissuade people from stories that they, or their editors, were not ready to take on in the first place.

As trainers, we coach from the sidelines; it is the reporters and their editors who must decide whether or not to put their organization behind a controversial story. After all, it is they who could be fired or find that all the copies of their newspaper suddenly disappear, and it is they who could have their station suddenly lose its license or be visited in their office by heavy-set bodyguards of criminal kingpins. All of these events have happened in very recent years to Armenian editors who have pushed the unspoken limits too far.

I sometimes fear that our training opened people’s eyes and ambitions to the kind of journalism that can be accomplished at some of the best news organizations operating in a free society, but then returned them to their situations with little armor against what the reporters refer to as “the Armenian reality.” Yet as repressive and punishing as oppressive forces of government and criminal corruption can be, reporters in Armenia show time after time their agility in getting stories done—perhaps sometimes in less than perfect fashion than might be wished, but nevertheless done. They play a dangerous game of thrust and parry, advance, retreat. Stakes are high. Punishments are visible, swift and serious.

The 10 participants were from a wide range of organizations and included television and print reporters who worked in newspapers, magazines and online. While some of the reporters were already very experienced in tackling investigative stories, others were not. Likewise, the journalism philosophies of their news organizations also varied widely, from meek to crusading. We endorsed this wide range. Journalism training is after long-term results. Training as many people as possible to reach for higher standards increases the possibility of attaining them.

Investigative Journalism

When I was a reporter at the Inquirer, the newspaper’s policy was not to have a permanent investigative team. Instead, reporters at every level had the opportunity to pursue an in-depth story if they came up with a good idea. At the Inquirer we shied away from the term “investigative reporting,” in favor on “in-depth,” “enterprise,” or “project” reporting. One reason is that we felt that important, in-depth stories should not always have to reveal corruption or catch bad guys. Probing accounts of health, environment and social issues can be equally, if not more, important.

In Armenia, everything reporters do could be considered investigative reporting, because they have to fight for every bit of information. Our training aimed not only to foster ambitious story selection, but also to help reporters in their daily work by encouraging them to base stories on facts and documents while aiming for fairness and balance. Many of the 10 Armenian reporters asked for and received government documents, often to their surprise. Some found the documents to be unreliable, but that, too, is a fact that needs to be reported in a country struggling for transparency. Sometimes the reporters had to scale back their original ideas when obstacles proved too difficult, for now. In training we focused on preparing alternative “minimum” stories to do if the “big one” becomes too elusive.

After my two weeks in Armenia, it was all too apparent that this developing country has made great strides but is struggling to hold onto a tenuous democracy, with only limited freedoms and restricted access to information. Yet I left convinced that these 10 journalists are likely to be important players in Armenia’s future as an open society.

Lucinda Fleeson, a 1985 Nieman Fellow, is the director of the Hubert H. Humphrey Fellowship Program at the Philip Merrill College of Journalism, University of Maryland, which brings outstanding journalists to campus for a year of academic and professional pursuits. Her training manual, “Dig Deep & Aim High: A Training Model for Teaching Investigative Reporting,” is published by the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) and has been translated into 18 languages and distributed worldwide. This article is adapted from her new training guide, “On the Right Track: Investigative Reporting in Armenia,” also published by ICFJ, in both English and Armenian.