Joy Mayer, the founder and director of Trusting News, has spent a decade studying how audiences relate to journalism — including how their trust is earned and lost. A former professor at the Missouri School of Journalism, Mayer now helps newsrooms bridge gaps and build stronger connections with the communities they aim to serve.

The idea for Trusting News, which was founded in 2016, came about when Mayer was advising a cohort of student journalists on their local reporting assignments. She said she noticed a troubling trend: community members did not accord journalists the same faith as she did in viewing them as forces for good working in behalf of the public interest.

“When I talked to journalists about that, they were depressed, they were defeated, and they had no idea what to do,” Mayer said. “And so I thought, ‘There's got to be something we can do about that.’” Mayer embarked on learning about other industries’ efforts to earn trust and recruited other journalists to join her. This collaboration eventually became Trusting News.

Mayer spoke to the current class of Nieman Fellows about best practices for gaining trust, including taking care over word choices and exhibiting transparency in the news-gathering process. Edited excerpts:

Fundamentally, what we’re trying to get newsrooms to do is to think about the obstacles to trust. What is preventing people from accessing what you’re doing, from understanding what you’re doing, and from finding what you’re doing credible?

The answers are not that complicated. Part of it is transparency — what do people not understand about what you do? And how are you explaining everything from your ethics, your funding, your corrections, how you decide what to cover, how you pick sources, and how you treat sources?

Then there’s the engagement piece, which is being in continual contact with the people you aim to serve, and understanding what you’re getting wrong — which most newsrooms do not prioritize in a way that I consider meaningful.

At the core of this is intellectual humility — a curiosity about who you’re not serving, who feels seen and understood by your journalism, and who feels neglected or misrepresented by your journalism, and what you’re willing to do to change that. I see intellectual engagement with those ideas much more than I see an institutional commitment to change based on those ideas.

Our downfall at Trusting News is that we work with a lot of individual journalists who don’t have an institutional commitment to change.

If I don’t have buy-in at the top, journalists are limited in what they can do. So an individual journalist can go on their own social media and say, “Here’s how I did this story, and here’s what I was careful to do, and here’s how I operate.” But unless it’s part of their content management system in a way that makes that easy, unless their boss says it’s OK to do it, unless they have an ethics policy they can link to, it’s all very difficult.

The biggest category in which I think we are failing is in explaining what makes us fair. If the biggest complaint about journalism in the U.S., at least at the moment, is [that] people assume that we are not open-minded [or] even-handed, that we fuel polarization, that we have a bias, then what is our counter-narrative? I’m hard-pressed to come up with examples that I think do that very effectively, and that is mystifying to me that we would not be directly addressing it.

It’s easier to find examples of where journalism is explaining very specific things. I mentioned that I advise The New York Times to explain anonymous sources. Many people don’t understand that when you allow a source to go unnamed, there’s a whole process behind that. So [The Times] started to include a box with their stories that says, “Here’s how we handle unnamed sources.”

Things like that are easy to get on the record, but the bigger picture of people’s perception of what we do is harder to attack.

I think the biggest problem is a lack of intellectual humility on the part of journalists … a gap between journalists’ declarations that they want to serve their audience and recognition — that you serve the audience you have, not the audience you wish you had — and curiosity about what it would take to close that. There are a lot of other corporate incentives, training, and research needed.

We are also not honest about our biases as journalists. About 80% of journalists live in New York, Washington, D.C., or Los Angeles. Journalism is rooted in urban, liberal perspectives, and we do not talk about that.

The number of journalists I hear from that feel like they have to be closeted in the newsroom, about their faith, about their politics, about their kind of history with law enforcement or military, like they just do not want to raise their hand and challenge assumptions in newsrooms — that is a problem, I think.

We have a resource about this — an anti-polarization checklist for newsrooms. We send a lot of signals in our journalism about where we stand and how we see the world, what we find normal or abnormal, what we see as the good side and bad side of issues [through the language we use].

Some of the language that’s loaded or that sends a signal of where we are is very simple — like the word “only.” If you say as a national news outlet that a house “only” costs $500,000, you’re sending a signal of what’s normal to you.

I talked to an editor whose reporter was writing a story about a farming issue, an agriculture bill, and the reporter turned in a story that said, “the little-known farm bill.” Well, who is it “little-known” to? It’s not little-known to the people who are affected by it and the community where you’ve just been reporting. It was little-known to you until you were given the story assignment.

I’m working with an investigative reporter in Milwaukee right now who’s doing a lot of work around guns and gun safety. And boy, has he changed the language he uses. What does “gun safety” mean? What does “gun violence” mean? These are terms that are not perceived equally. He set out to report on this with the premise: can we do this story in a way that doesn’t shame gun owners? This shouldn’t be radical, but it is kind of radical to start a reporting project [while] understanding that journalism often shames people who have a specific relationship to that topic.

I feel like people spend their trust in a lot of different ways. A woman I know told me, “I trust everything Rachel Maddow says. I’m not going to pay attention to the rest of it.” People say the same thing about Sean Hannity or Tucker Carlson.

[People think,] “I don’t want to have to look for information. I want it to find me.” Wherever people are spending their time, if there’s somebody who feels like a trusted friend saying, “I’ve got you, don’t worry about it. Here are really the five things you need to know about [X],” or “Let me just give you the basics” – in some ways, I think that can be really responsible and effective and mission-driven.

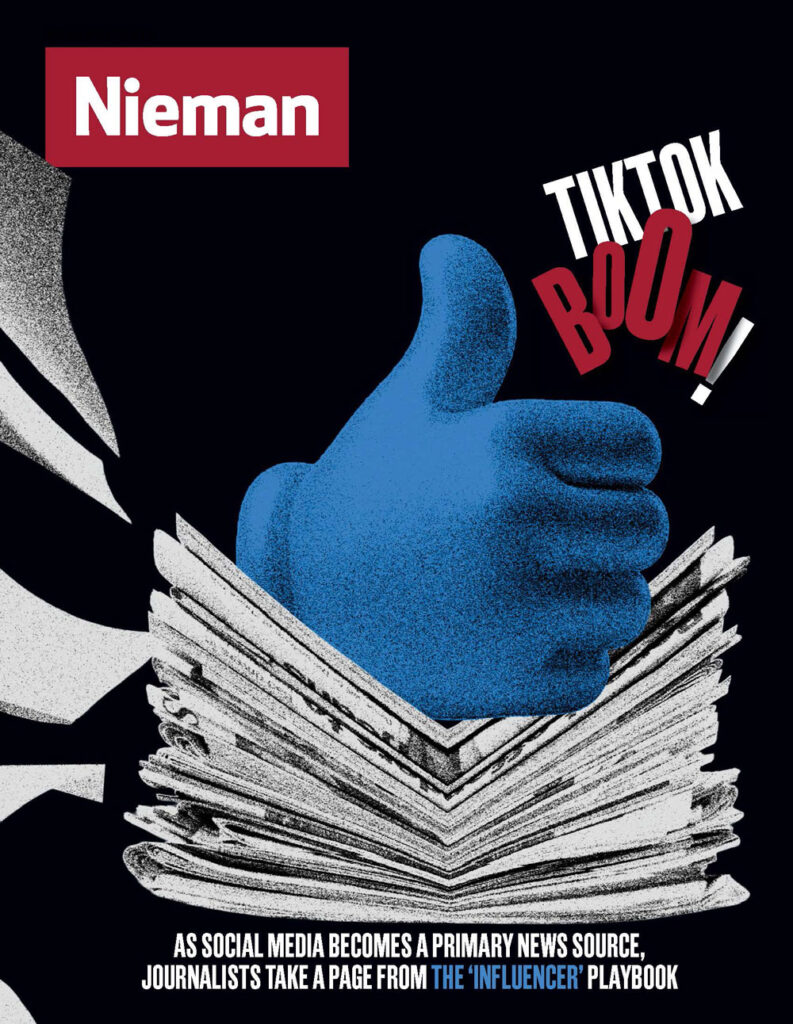

I think it’s possible to be a very well-informed news consumer mostly through creators. It all depends on who’s in your feed, right? I’m tired of the industry’s response of being defensive, saying, “Oh, if it’s on TikTok, it can’t be credible.” Of course, it depends on who you follow on TikTok. That’s what they said about blogs back in the day: “That’s not journalism. It’s a blog.”

I was teaching a class on citizen journalism back in the early 2000s, and I’d say, “A blog is a platform for publication where the newest story goes at the top. It’s not a type of content,” and I feel like there’s a lot of that happening in the industry right now.

In terms of navigating the creator space, or partnering with creators, I feel like we have some rocky patches ahead, figuring out the ethics of that, the mission of that, the finances of that. Because creators, in a lot of cases, are not linking back to or even mentioning the original sources, and therefore the reporters actually doing the work are not getting any credit or any audience benefit. There’s a lot to figure out.