RELATED WEB LINK

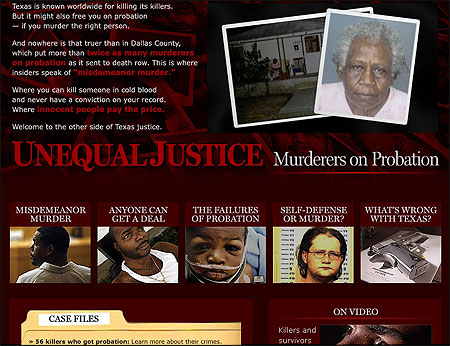

Watch the multimedia presentation of “Unequal Justice” »What would a big newspaper investigation look like if conceived primarily for the Web? What would we do differently? Would the medium affect our reporting? And could we do an equally good job in both digital and print with the resources we had?

These questions were on our mind when The Dallas Morning News’s idea for the investigative series “Unequal Justice” arose. This project, reported by Brooks Egerton and Reese Dunklin, grew out of an earlier story Egerton wrote about two men in Dallas—one African American and poor, the other politically well-connected and white—who received dramatically different sentences for probation violations from the same judge.

Though we couldn’t yet answer our questions, we did know that if journalism’s future is on the Web, then investigative reporting had to stake out its position. Digital journalism could not be the sole domain of breaking news and blogging, and it had to be more than the repository of electronic reprints. We believed the Web offered fertile ground for investigative projects; talented journalists could creatively pursue a story using digital tools and then engage readers with multimedia presentations showing what they’d found. Armed with this belief, we set out to see if we were right.

“Unequal Justice: Murderers on Probation” revealed how killers could get the lightest possible sentence in a state legendary for its tough-on-crime image. The reporters spent months researching murder cases throughout Texas; they examined court records and built databases to augment the state’s faulty official files. This helped us identify the series’ major themes and select the cases that best illustrated them. We also decided that the strongest online elements would be the killers’ and victims’ families talking on camera about crime and justice in Texas.

I figured a multimedia investigative project would be more labor intensive than a print one. (And, by the end, it was about 50 percent more work.) We were learning as we went, which meant finding our way from the start along with other colleagues at the newspaper, including photographers, videographers, graphic artists, and Web designers. While we typically work with them closely throughout regular investigations, this time the collaboration would have to be deeper, with more give-and-take on reporting and editing approaches, if we hoped to ensure success.

What we did not anticipate were the benefits a multimedia approach would bring to our overall reporting and how it would enhance our investigation and storytelling in print as well as on the Web.

Visual Evidence

A lot of what we needed to do with this project involved reconstructing past events. This meant that dynamic visuals were limited. Another challenge involved our key interview subjects; either they were camera-shy survivors, imprisoned killers available for only a limited time, or murderers on probation, who we thought might be reluctant to talk. It seemed that most of our footage would be traditional face-to-face interviews, which might be boring.

So the reporters requested crime scene photos, access to physical evidence that the police had maintained, audio of 911 calls, and video of police interrogations. We thought this would provide visual material that could be spliced in between the main interviews. Even the best journalists don’t always seek to review this kind of primary source material, since often it is summarized and incorporated into official records, such as police reports, court filings, and depositions that are quicker and easier to get. But once the reporters actually saw or heard the evidence, they realized how much it strengthened their reporting.

One case, for example, involved a boyish, 19-year-old dropout and former gang member who was acquitted in the fatal stabbing of a gay waiter twice his age. The prosecution had argued it was a consensual liaison and that the teen lashed out in a moment of “gay panic.” The waiter was stabbed 38 times; his mother said he looked like a saltshaker. The teen claimed he killed in self-defense to thwart a rape and told the court that the two men struggled in the waiter’s bedroom before falling onto the bed, where the stabbing occurred.

Yet crime scene photos showed bookcases and nightstands just feet from the bed, with knickknacks and framed photos undisturbed. Police reports didn’t delve deeply into such details, and the prosecutor in the case was initially reluctant to talk. Seeing the pictures enabled the reporters to visualize the crime scene, ask smarter questions, convince the prosecutor and jurors to discuss the case and enrich the story with details that called the verdict into question. The reporters also were able to press the teen about his version of events, leading to an animated on-camera exchange in which he acknowledged he had become enraged by the waiter’s pass. “‘You’re out of here, David.’ That’s what I thought in my head,” he told us.

Approaching the investigation from a multimedia perspective not only made for a more complete and interesting story, but it enhanced accuracy and provided transparency. On our Web site, visitors heard 911 calls and the tone of voice of a father who shot and killed his 18-year-old during an argument about the son’s girlfriend. We made it possible to see what the crime scenes looked like then and now by shooting new visuals from the murder sites that complemented photographs from the day of the killings. Online users could watch survivors talk about the painful consequences of unequal justice and judge for themselves whether killers on probation exhibited remorse or ruthlessness. As one young killer, Jason Chheng, told us on camera, pulling on his Marlboro and chuckling about how he had remained on probation despite repeated violations, “The justice system is all screwed up.”

In addition to watching the videos, shot by our staff news photographer Kye Lee, Web users could examine the findings of our computer-assisted analysis of killers on probation via an interactive graphic. And they could peruse detailed case summaries on the 56 killers who received probation in north Texas from 2000 through 2006.

Connecting to Readers

RELATED WEB LINK

“Faces of TYC”

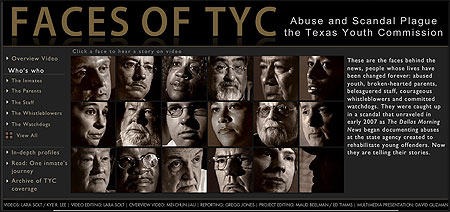

-www.dallasnews.com/tycWe’ve also found that even limited multimedia elements can enhance and elevate print investigations. A team of reporters, led by Doug Swanson, spent most of 2007 investigating and writing about the Texas Youth Commission (TYC), the state’s juvenile justice agency. Sexual and physical abuse of young inmates at TYC had become so commonplace that prison administrators traded sex for birthday cake, and kids were incarcerated well beyond their sentence if they didn’t acquiesce. The reporting exposed crimes and cover-ups that resulted in the firing or resignation of the entire TYC leadership and freedom for many young inmates. It convinced the state legislature to enact sweeping reforms, and it was the talk of the Texas power elite.

Even so, the wrongdoing we’d uncovered was not resonating with average readers in quite the same way. It was clear to me that we needed to find another way to connect our readers to the human toll of our hard-core investigation. That led us to create “Faces of TYC,” a multimedia video package by reporter Gregg Jones and photographer Lara Solt in which the key stakeholders—young inmates, parents, staff, whistleblowers and watchdogs—talked about the consequences of this tragic scandal. In-depth profiles and the prototypical story of one young inmate accompanied the videos. The multimedia package also served to anchor online our TYC story archive.

For both multimedia projects, our photo department created something we call “the overview video,” a summary of the best on-camera interviews and multimedia elements that works like a movie trailer. We posted the overview videos for both “Unequal Justice” and “Faces of TYC” on YouTube in advance of publication to increase interest in our work.

These investigative projects, while early efforts, gave us many of the answers to questions we once had. What makes multimedia projects work also enriches our reporting. The online project gives our findings greater reach and resonance, and Web users can access primary source information to verify or question our findings. Now we not only seek project ideas that lend themselves to a multimedia approach, we’re on the lookout for even more imaginative ways to use the Web for investigative reporting and to engage readers. Stay tuned!

Maud Beelman is deputy managing editor for projects and enterprise at The Dallas Morning News. Projects reporter Reese Dunklin contributed to this article. “Unequal Justice” won the 2008 Online Journalism Award for investigative reporting, and “Faces of TYC” won the 2007 Sigma Delta Chi Award for Public Service in Online Journalism.