It is said that history is written by the winners of its wars. History is war’s ultimate prize, since for the victor, it is his to shape. Often, what forms the content of history comes from the daily accounts amassed by the winning side’s journalists. If journalism can be described as the minute-taker of human existence and history is its library, what happens when a historical document conveys no point of view, when it tells only about universal truths? Whose library will it then belong in? Who will identify and claim it as theirs?

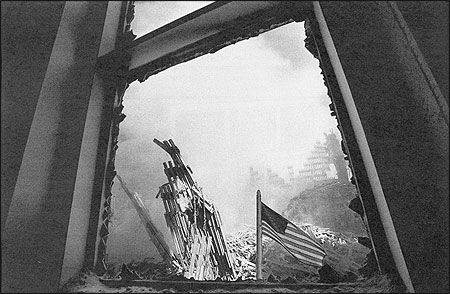

The coverage of America’s war on terrorism began on September 11, 2001 with an image of a plane flying into the World Trade Center’s south tower. To the citizenry of earth this image was as unbelievable as Neil Armstrong’s 1969 moonwalk. A few days later, an image from Ground Zero showing firemen hoisting the Stars and Stripes equaled that of the doomed jetliner splash in its surrealism, mirroring what had been done on Iwo Jima 60 years earlier and making the case for manipulation. Or was it just media déjà vu? Soon the faces of Muhammad Atta, Osama bin Laden, Saddam Hussein, and John Walker Lindh, “the American Taliban,” would fill our screens like wanted posters on the saloon doors: Dead or Alive. And finally, the statue of the dictator himself toppling over, replayed again and again, symbolizing the end of a speedy war, when in truth things were only just getting started.

The last two years can be summarized this way, along with the headlines, catch-phrase journalese, and partisan slogans of “Shock and Awe,” and “Mission Accomplished.” Never had a war been so widely reported on, and yet never before had the people understood so little. The logic appeared to be that to reveal anything more would mean the terrorists had won.

“War” is a photo-documentary book published by de.MO and dedicated to this recent slice of history. In it, clichés and icons are omitted, replaced instead by skepticism and everyday facts. In its 415 pages of pictures and narrative, “War” provides evidence based on the principles of physics, not on subjectivity, showing effects from consequences and actions causing reactions. It’s hard-hitting, but impartiality always is.

Through the images captured by VII, a photo agency renowned for its collection of veteran documentary photographers, “War” brings to our attention every vivid detail, whether we like it or not. Working side-by-side with other journalists and photographers, the men and women of VII photographed that which sought to show rather than tell. “There was a consensus made by all the photographers and myself that this book needed to be impartial,” says Giorgio Baravalle, de.MO’s editor and publisher. And the book adheres to these principles as it moves through the events of September 11th to the White House and war room at the Pentagon, then captures the reaction of the Taliban and its supporters’ anti-American fervor, before ping-ponging from these shores to the deserts and mountains of the Arabian Peninsula and Central Asia, returning home again, and then on to Iraq.

The publisher makes no apologies for the book’s length, something almost outdated with news these days. “The reason why it’s big, thick and heavy is because the subject matter is big, thick and heavy,” Baravalle notes. To see the book is to know how true this is, and to look inside is to know this is also an understatement. In one picture, an Iraqi rolls around in agony, gripping his leg, as a G.I. stands poised, his weapon raised. In another, a U.S soldier lies dead and twisted, as his platoon members scamper around cleaning up. And in another photograph, a soldier holds in his hand the charred lower half of a man’s leg still with its shoe and sock on.

But there’s more to “War” than just the slathering of shock. History should be more than specific events targeted to a particular audience. It should be the aggregate of past events as they relate to the human condition and therefore must digress and put events in context while also satisfying curiosity and offering insights along the way. Unfortunately, only in a perfect world do such progressions exist. Baravalle knew this from the outset. “Impartiality isn’t appreciated at all,” he said. “But it’s something that needs to be done. Who wants to read a history book that has no answers?”

A white horse gallops through a battered landscape and offers balance to the bullets. Balloons dissect a foreign horizon to underscore a military showdown. These images, along with those of families in the midst of war, show the Western reader that our enemy is no less human than we are ourselves. “Agendas dictate content … and the war was covered on the principle of what would sell,” says Chris Anderson, a VII photographer. “This book gave us a chance to do what we wanted … [to] show what we really saw.” Here it is, the crux of the matter: News is a product and adheres to the dictates of the marketplace. Its cut-down form reflects the way news has had to adapt in order to be profitable and survive. Eye-grabbing icons and sensational copy too often transform print journalism into a vehicle for the dramatic, catching the moment, while missing the larger point: War is hell.

An American flag raised by New York City firemen at Ground Zero on September 11, 2001. Photo by © James Nachtwey/VII.

The Adhamiya district of Baghdad, July 2003. Photo by © Antonin Kratochvil/VII.

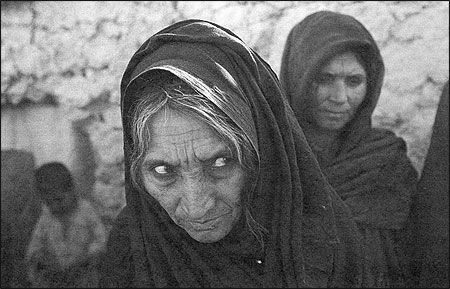

Idi Amma, left, an elderly Afghan refugee from Erat, by the small mud house she and 34 other Afghan refugees share in the Ghoussabad neighborhood in Quetta, Pakistan, September 2001. Photo by © Alexandra Boulat/VII.

Northern Alliance fighters drive a captured Taliban tank back to their lines in Kunduz, Afghanistan, November 2001. Photo by © James Nachtwey/VII.

A Book Without an Ending

War is about taking sides and often, so is journalism. We are told we learn from history, that history helps us in not repeating the mistakes of the past. And yet, we don’t learn, and history doesn’t help while there are sides taken. On the front page of New York’s Daily News in November 2003 there was a full-page picture of a G.I.’s smoldering remains in the city of Mosul, Iraq. The headline read “Bastards!” Journalism stirs, but does so for the wrong reasons. In times of war, the skeptic is quieted, shipped off, and ignored.

“Americans don’t want to buy a book that reminds them of the reality outside their country,” says Baravalle. “War” is a book that does this and has looked into the heart of the matter and done it proud, if that is the right feeling one should have after closing its covers.

There are two images that speak volumes for what “War” strives to do. From just above the rubble of the towers stands Old Glory. The flag is small, insignificant, but provides what color there is in the chalky white of what was downtown, while above, a blue-black sky amplifies the starkness. The scene is empty, void of life. It is a quiet image despite the colossal devastation, focusing the eyes to linger. Here the epic begins. Four hundred and fourteen pages later an image of an Iraqi boy standing on a roof, grabbing at something in the sky, brings the curtain down on all of the photographs that have come before. The picture implies nothing, is noncommittal and open-ended in an unsettling sort of way. Antonin Kratochvil, another VII photographer, says that this last image, which he took, and the many pictures like it in the book, move beyond the immediacy of first impression. “The last image is about transcendence. It’s why we chose it,” he says. “We knew putting this book together that the war wasn’t over, and wouldn’t be … for a long time. The boy represents what remains no matter which side you’re on … he represents the human spirit.”

There is no end to “War,” be it in the book itself or in the practice thereof. Unfortunately for the book, its commercial success depends on its ability to engender in readers a sense of hope and be able to offer guarantees. This it can’t do. It doesn’t have answers for which we are so desperate. Journalists working on both sides of the war were embedded in the field, their words and images censored to greater or lesser degrees, and then, on return, censored again by their publications, in order to do just this—reassure. As Anderson says: “You shoot for yourself when you’re out there. And even though that’s my intention, I’m always thinking ‘I have to please my client.’ After all, they’re paying.”

What “War” achieves and what gives it its strength is its adherence to what the photographers saw. Their images convey the outsider’s point of view, straddling the “pros,” “antis,” and “nons” of every movement—and that of the skeptic—avoiding the usual finger pointing and rose-colored perspectives.

“If you have children you’ll understand, this is for them,” says Baravalle. History is what our children inherit from us, but it also can be the looking glass in which we see ourselves. “No one won this war,” reflects Anderson. If the image of Flight 175 crashing into the south tower left you shocked at what one side could so quickly inflict, Baravalle and VII’s “War” will do the same. Except, this time, the shock will be all encompassing, a feeling we should all have if history is to serve us well.

Michael Persson is a freelance writer and photographer, who has been published widely on topics of photojournalism and media. He worked as a photographer during the fall of the Berlin Wall, through the revolutionary changes in Eastern Europe, the first Gulf War, the breakup of Yugoslavia and the former Soviet Union, as well as in South Africa during its path to democracy.