Since February 2003, Meryl Levin and Will Kanteres documented the day-today experiences of staffers, who are the backbone of presidential campaigns. Their book “Primarily New Hampshire” and an accompanying exhibition will be released in this summer. The authors note that “Rather than focusing on the candidates themselves, we chose to document in photographs and their own words the experiences of more than 25 young politicos who dedicated a year of their lives to working on the various presidential campaigns in New Hampshire.” The following pages feature work from this project.

Every four years dozens of political activists decide to give up a year of their lives to be a part of our democratic process. During this time, they will eat, drink and breathe politics. Their birthdays will pass uncelebrated, and relationships with friends who aren’t political (or who aren’t registered to vote in New Hampshire) will be neglected.

These are the characters in the passion play we have chosen to explore. The inspiration that drives these campaign workers varies as much as their individual talents, techniques and personalities. Yet they share similar missions—to communicate their candidate’s message, gather support from the state’s voters, deliver voters to the polls on Election Day, and ultimately to win the most votes.

The work performed on the campaign is a lot like an iceberg, where the general public only sees 10 percent of what goes on and most of the energy, testing and workload is in the 90 percent that goes unseen. “Primarily New Hampshire” reveals the culture, skills and commitment that develop among young staffers in New Hampshire’s political boot camp.

This project exists, in part, out of our concern that the democratic process is gradually becoming more alien and less accessible to the American public. (Only 50 percent of eligible voters participated in the last presidential election.) Our hope is that by sharing these photographs and young people’s words Americans will gain a better understanding of the level of commitment this kind of engagement requires. We hope, too, that “Primarily New Hampshire” inspires more people to become involved in the democratic process or, at least, fulfill their fundamental obligation of citizenship—by casting a vote.

Meryl Levin is a social documentary photographer whose work has focused mainly on issues of health care and social welfare, housing and education. Her photographic essays, including material from her book, “Anatomy of Anatomy” (2000), have been published worldwide. Will Kanteres, a New Hampshire native, has been active in presidential and local politics for more than 20 years. “Primarily New Hampshire” is made possible in part by support from the New School University. To see more of the photographs in their original color and read additional text, go to www.PrimarilyNewHampshire.com.

As in the upcoming book, the speaker in the caption is not always the same as the person in the photograph.

“Only in New Hampshire can a young activist with just a few years experience be hounded by each and every campaign, receive calls, letters, postcards from the candidate and members of his family, and be lobbied by prominent state politicians from every angle. I quickly became desensitized to all the correspondence. I remember being nonplussed one afternoon upon receiving a call from John Kerry himself, even as I was deciding whether I wanted to take a job on his campaign. I knew things were getting intimate when Mrs. Lieberman said in a message, ‘We need you on our team, honey.’” —Christopher Pappas, April 2003, deputy field director, Joe Lieberman campaign

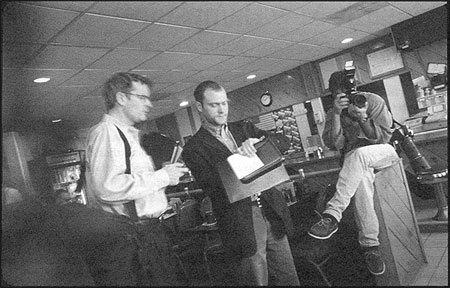

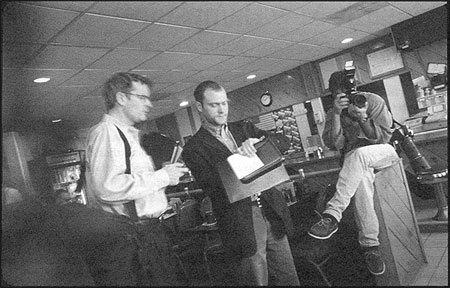

“Running an event is like cooking. You have to have a sense in advance of what the ingredients are; what has to be done; how long each step will take, and what this final product is supposed to look like.

“You have to be able to do several things at the same time—keep reporters abreast of what will happen, make sure the visual is laid out right, and make sure the participants are in the right spot. Then you have to be able to monitor everything and make sure nothing is ‘burning’ (too small of a crowd, an embarrassing backdrop, a late-breaking story that one reporter is working on). And like any good cook, you have to taste along the way, adding a bit more here or there, prompting a question and then bringing the event to a close.

“Also like cooking, the hardest part is usually timing. Far too often, it’s (past) time to go, and no one wants to leave. Edwards wants to keep taking questions, the audience wants to keep asking them. The reporters want to grab him by the door and meanwhile another event on the other side of town is supposed to start right about now. You do your best to plan the times right in advance, but you end up slightly off in the end, and you struggle to make sure the steak is ready and at the same time the side dish is warm.” —Colin Van Ostern, May 2003, New Hampshire state press secretary, John Edwards campaign

“In my few years working on campaigns, I’ve heard one phrase over and over: The most important things in any political race are people, money and time. And I’ve learned that everything else you want or need to do stems from these three. You can always find more people and money—you can’t find more time. Time—months, days, hours, minutes—and how you utilize it until the voting booths close on Election Day is the most critical aspect of any race. In the life of an individual staffer, that means that time spent not working is potentially hurting the candidate and the campaign. There is always more to do, and there is pressure on all of us.

“Yet this obsession with time makes you realize that time is passing not just inside the campaign world, but outside in the ‘real world’ as well. I find that I feel guilty whatever I choose to do, because I know that I won’t be able to get back the time I’m missing in either world. I try to maintain a balance, knowing that campaigns are always short-term. Losing myself in the campaign is a sacrifice I’ve made in order to be in this business and to be part of the democratic process. I just hope that I can find my way home when all this is over.” —Emily Silver, July 2003, New Hampshire state deputy campaign director/chief of staff, Joe Lieberman campaign

“July 4: Everybody loves a parade! Close to 100 people march with Governor Dean in the Amherst and Merrimack parades. We have the loudest, proudest float. The most signs. The most energy. And Dean is awesome. Senator Graham is a nice guy, and he says a genuine hello to everyone, including the crowd on the Dean truck. Lieberman is nice, too, but he only says hello to nonpolitical floats and folks. Kerry stays with his team for most of the time. But Dean, he’s everywhere. Shaking hands. Waving at everyone. Giving impromptu speeches from the bullhorn. It was awesome (but the sunburn will last a week).” —Tom Hughes, July 2003, New Hampshire state field director, Howard Dean campaign

“In the middle of the afternoon on July 10th, I answered my phone and heard Governor Howard Dean’s voice on the other end of the line. He had called to ask if I had chosen to stay on the campaign after the summer to work as the office manager and statewide volunteer coordinator until the primary. I said yes. It was the first time I had said it out loud to anyone. Up until then I had toyed with the idea of taking time off to continue working, but when others asked me about my decision I usually said, ‘I’m still thinking about it.’ I’d roll my eyes at the thought of dealing with my supportive but concerned family, explaining my nontraditional semester to my friends, and pleading with Hamilton College to allow me to stay on the campaign and still graduate with my classmates.

“On the back wall of the office, tucked in an unseen corner, is a timeline of our campaign. The most important pictures and dates in the lifetime of Governor Dean and the campaign are represented. Since May 19th, a small Polaroid picture of my face has been a part of that colorful, handmade poster. Since then, many pictures and milestones have happened, and I can’t imagine not continuing to participate in the story of this campaign. It feels good to have made a choice about what to do this fall. Watching the excitement of this campaign from my dorm room in Clinton, New York would never have been an option.” —Rachel Sobelson, July 2003, operations manager/volunteer coordinator, Howard Dean campaign

“I think that a certain culture definitely begins to take shape on a campaign. … The field staffers, average age of about 25, are the privates. They won’t fraternize with Judy or Ken [senior staff]. The field director deputies are like sergeants, they lead two squads of field staffers. I’m like a captain, I oversee the field deputies, but will have increasingly less and less interaction with the field staffers. And Ken is the general, overseeing not only the field staff, but also the other divisions of press and politics, each of which will have their own hierarchy.

“It’s also interesting to watch the interaction of the field staffers. Because they are so young and for the most part from out of state, they have no friends or family in the area except for their coworkers. So they spend nearly all their time with other campaign staff. I am from New Hampshire and go home to my wife every night, something that I’ve always done on campaigns.” —Nick Clemons, May 2003, New Hampshire state field director, John Kerry campaign

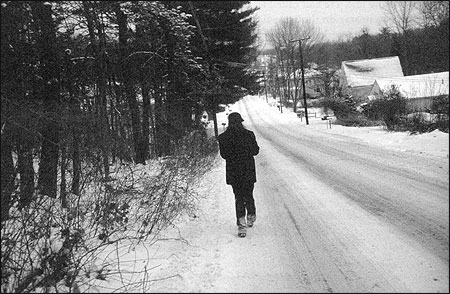

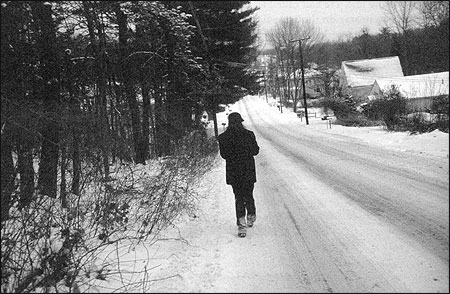

“Sometimes, as I walk the streets of Nashua, I feel as if I, as if we, the politicos, are the only ones out there. All alone, going door-to-door.

“I knew enough to not expect a warm welcome—I’d canvassed for several campaigns in Missouri while I was in college. But something about this election—the presidential, and this state, New Hampshire—led me to believe that maybe, just maybe, folks would be excited. For the most part, the doors I knock on are answered by average citizens, no more or less engaged than my parents or their friends. ‘It’s awfully early,’ many begin. And not because they don’t like my candidate, but because they don’t particularly like politics, the pursuit of power. But when I get into my spiel—Dean balanced the budget 11 years straight in Vermont, health care for virtually all children, 92 percent of adults, etc.—they get interested. Start criticizing Bush, embracing the doctor.

“The early evening is already my favorite time of the day to canvass. I’m three-quarters of the way into my shift. Signed up a supporter or two, converted an ex-Kerry backer, got a couple doors slammed in my face—the whole range of responses. But I invariably get a second wind. Talking to a young voter I persuade to register. Learning about how a single mom without health insurance is getting by. Conversing with a man fixing his car and persuading him to pause for a moment, to learn about the governor.

“As I walk by the apple orchard, the sun sets. A beautiful scene. The sky is a million shades of red, pink, blue. But all is quiet. And I keep walking.” —Yoni Cohen, June 2003, Salem/Derry field staff, Howard Dean campaign

Every four years dozens of political activists decide to give up a year of their lives to be a part of our democratic process. During this time, they will eat, drink and breathe politics. Their birthdays will pass uncelebrated, and relationships with friends who aren’t political (or who aren’t registered to vote in New Hampshire) will be neglected.

These are the characters in the passion play we have chosen to explore. The inspiration that drives these campaign workers varies as much as their individual talents, techniques and personalities. Yet they share similar missions—to communicate their candidate’s message, gather support from the state’s voters, deliver voters to the polls on Election Day, and ultimately to win the most votes.

The work performed on the campaign is a lot like an iceberg, where the general public only sees 10 percent of what goes on and most of the energy, testing and workload is in the 90 percent that goes unseen. “Primarily New Hampshire” reveals the culture, skills and commitment that develop among young staffers in New Hampshire’s political boot camp.

This project exists, in part, out of our concern that the democratic process is gradually becoming more alien and less accessible to the American public. (Only 50 percent of eligible voters participated in the last presidential election.) Our hope is that by sharing these photographs and young people’s words Americans will gain a better understanding of the level of commitment this kind of engagement requires. We hope, too, that “Primarily New Hampshire” inspires more people to become involved in the democratic process or, at least, fulfill their fundamental obligation of citizenship—by casting a vote.

Meryl Levin is a social documentary photographer whose work has focused mainly on issues of health care and social welfare, housing and education. Her photographic essays, including material from her book, “Anatomy of Anatomy” (2000), have been published worldwide. Will Kanteres, a New Hampshire native, has been active in presidential and local politics for more than 20 years. “Primarily New Hampshire” is made possible in part by support from the New School University. To see more of the photographs in their original color and read additional text, go to www.PrimarilyNewHampshire.com.

As in the upcoming book, the speaker in the caption is not always the same as the person in the photograph.

“Only in New Hampshire can a young activist with just a few years experience be hounded by each and every campaign, receive calls, letters, postcards from the candidate and members of his family, and be lobbied by prominent state politicians from every angle. I quickly became desensitized to all the correspondence. I remember being nonplussed one afternoon upon receiving a call from John Kerry himself, even as I was deciding whether I wanted to take a job on his campaign. I knew things were getting intimate when Mrs. Lieberman said in a message, ‘We need you on our team, honey.’” —Christopher Pappas, April 2003, deputy field director, Joe Lieberman campaign

“Running an event is like cooking. You have to have a sense in advance of what the ingredients are; what has to be done; how long each step will take, and what this final product is supposed to look like.

“You have to be able to do several things at the same time—keep reporters abreast of what will happen, make sure the visual is laid out right, and make sure the participants are in the right spot. Then you have to be able to monitor everything and make sure nothing is ‘burning’ (too small of a crowd, an embarrassing backdrop, a late-breaking story that one reporter is working on). And like any good cook, you have to taste along the way, adding a bit more here or there, prompting a question and then bringing the event to a close.

“Also like cooking, the hardest part is usually timing. Far too often, it’s (past) time to go, and no one wants to leave. Edwards wants to keep taking questions, the audience wants to keep asking them. The reporters want to grab him by the door and meanwhile another event on the other side of town is supposed to start right about now. You do your best to plan the times right in advance, but you end up slightly off in the end, and you struggle to make sure the steak is ready and at the same time the side dish is warm.” —Colin Van Ostern, May 2003, New Hampshire state press secretary, John Edwards campaign

“In my few years working on campaigns, I’ve heard one phrase over and over: The most important things in any political race are people, money and time. And I’ve learned that everything else you want or need to do stems from these three. You can always find more people and money—you can’t find more time. Time—months, days, hours, minutes—and how you utilize it until the voting booths close on Election Day is the most critical aspect of any race. In the life of an individual staffer, that means that time spent not working is potentially hurting the candidate and the campaign. There is always more to do, and there is pressure on all of us.

“Yet this obsession with time makes you realize that time is passing not just inside the campaign world, but outside in the ‘real world’ as well. I find that I feel guilty whatever I choose to do, because I know that I won’t be able to get back the time I’m missing in either world. I try to maintain a balance, knowing that campaigns are always short-term. Losing myself in the campaign is a sacrifice I’ve made in order to be in this business and to be part of the democratic process. I just hope that I can find my way home when all this is over.” —Emily Silver, July 2003, New Hampshire state deputy campaign director/chief of staff, Joe Lieberman campaign

“July 4: Everybody loves a parade! Close to 100 people march with Governor Dean in the Amherst and Merrimack parades. We have the loudest, proudest float. The most signs. The most energy. And Dean is awesome. Senator Graham is a nice guy, and he says a genuine hello to everyone, including the crowd on the Dean truck. Lieberman is nice, too, but he only says hello to nonpolitical floats and folks. Kerry stays with his team for most of the time. But Dean, he’s everywhere. Shaking hands. Waving at everyone. Giving impromptu speeches from the bullhorn. It was awesome (but the sunburn will last a week).” —Tom Hughes, July 2003, New Hampshire state field director, Howard Dean campaign

“In the middle of the afternoon on July 10th, I answered my phone and heard Governor Howard Dean’s voice on the other end of the line. He had called to ask if I had chosen to stay on the campaign after the summer to work as the office manager and statewide volunteer coordinator until the primary. I said yes. It was the first time I had said it out loud to anyone. Up until then I had toyed with the idea of taking time off to continue working, but when others asked me about my decision I usually said, ‘I’m still thinking about it.’ I’d roll my eyes at the thought of dealing with my supportive but concerned family, explaining my nontraditional semester to my friends, and pleading with Hamilton College to allow me to stay on the campaign and still graduate with my classmates.

“On the back wall of the office, tucked in an unseen corner, is a timeline of our campaign. The most important pictures and dates in the lifetime of Governor Dean and the campaign are represented. Since May 19th, a small Polaroid picture of my face has been a part of that colorful, handmade poster. Since then, many pictures and milestones have happened, and I can’t imagine not continuing to participate in the story of this campaign. It feels good to have made a choice about what to do this fall. Watching the excitement of this campaign from my dorm room in Clinton, New York would never have been an option.” —Rachel Sobelson, July 2003, operations manager/volunteer coordinator, Howard Dean campaign

“I think that a certain culture definitely begins to take shape on a campaign. … The field staffers, average age of about 25, are the privates. They won’t fraternize with Judy or Ken [senior staff]. The field director deputies are like sergeants, they lead two squads of field staffers. I’m like a captain, I oversee the field deputies, but will have increasingly less and less interaction with the field staffers. And Ken is the general, overseeing not only the field staff, but also the other divisions of press and politics, each of which will have their own hierarchy.

“It’s also interesting to watch the interaction of the field staffers. Because they are so young and for the most part from out of state, they have no friends or family in the area except for their coworkers. So they spend nearly all their time with other campaign staff. I am from New Hampshire and go home to my wife every night, something that I’ve always done on campaigns.” —Nick Clemons, May 2003, New Hampshire state field director, John Kerry campaign

“Sometimes, as I walk the streets of Nashua, I feel as if I, as if we, the politicos, are the only ones out there. All alone, going door-to-door.

“I knew enough to not expect a warm welcome—I’d canvassed for several campaigns in Missouri while I was in college. But something about this election—the presidential, and this state, New Hampshire—led me to believe that maybe, just maybe, folks would be excited. For the most part, the doors I knock on are answered by average citizens, no more or less engaged than my parents or their friends. ‘It’s awfully early,’ many begin. And not because they don’t like my candidate, but because they don’t particularly like politics, the pursuit of power. But when I get into my spiel—Dean balanced the budget 11 years straight in Vermont, health care for virtually all children, 92 percent of adults, etc.—they get interested. Start criticizing Bush, embracing the doctor.

“The early evening is already my favorite time of the day to canvass. I’m three-quarters of the way into my shift. Signed up a supporter or two, converted an ex-Kerry backer, got a couple doors slammed in my face—the whole range of responses. But I invariably get a second wind. Talking to a young voter I persuade to register. Learning about how a single mom without health insurance is getting by. Conversing with a man fixing his car and persuading him to pause for a moment, to learn about the governor.

“As I walk by the apple orchard, the sun sets. A beautiful scene. The sky is a million shades of red, pink, blue. But all is quiet. And I keep walking.” —Yoni Cohen, June 2003, Salem/Derry field staff, Howard Dean campaign