The campus of Southern New Hampshire University lies at the end of hilly roads lined with tall pines. At 8 a.m. on the Sunday before the 2004 Democratic primary, it is New England picture-postcard beautiful, snow-dusted pine limbs breaking into a cloudless blue sky. It is also take-your-breath-away cold with temperatures hovering around seven degrees.

The guard at the university’s entrance gate is already bored with the monotony of repeating his directions. “Just follow those cars,” he says, as we crack the window of our rented SUV. Topping the hill, we can see that hundreds of cars already fill the parking spaces, 90 minutes before the start of this morning’s “Women for Dean” rally.

Three satellite trucks are parked outside the University’s Hospitality Center. Inside, the room is elbow-to-elbow and anxious aides have set up an overflow room with a television tuned to C-SPAN, which is also filling up fast. Ultimately, when that room reaches capacity, Dean aides have the unhappy task of turning aside another hundred or so arrivals on this critical final weekend of campaigning.

Equally as impressive as the voters willing to brave the frigid Sunday morning temperatures is the crush of media trailing the former Vermont governor. A dozen television cameras are lined up, aimed at the waiting podium. Our network, C-SPAN, has sent two cameras, a satellite uplink, two producers, an interviewer, and six technicians whose task it is to beam the event live to 80 million C-SPAN homes across the country; to listeners on WCSP, the FM station C-SPAN operates in Washington, and to Web users, who favor the network’s nonstop video stream of political events at C-SPAN.org. We will transmit live for nearly two hours—following Governor Dean through the crowd until the last voter hand is shaken. At this point in the campaign, it is the unscripted interaction between the candidates and voters that brings us our best material.

Governor Dean’s traveling press arrives with the candidate, grumbling about a room unable to fit them. Local police repeatedly clear the hallway of people attempting to jam themselves in the room’s three open doors and threaten to remove still photographers who have climbed on folding chairs at the back of those crowds, angling for a decent shot.

Standing outside, with Governor Dean’s stump speech echoing in the hallway, is a feast for political and media junkies. Republican pollster Frank Luntz circles, looking for a way to circumvent the closed-off access. Newsweek’s Jonathan Alter arrives, spouse and children in tow; MSNBC’s Chris Matthews talks it up with veteran television booker Tammy Haddad, then gets pulled aside for an interview with a Portuguese television crew. (“Not to worry, we have a translator,” he’s told.) A Boston TV anchor leans against the wall, gossiping about station politics with his predecessor, who is on hand to cover the event for the cable network he now works for. A radio reporter from India, tape recorder in hand, is unable to get inside the room and anxiously asks if she can plug her device into C-SPAN’s audio mult box. Numerous individuals are recording the scene with pocket-size video recorders or sending photos home instantly via cell phone.

It is a scene repeated throughout the day and for every one of the top Democratic candidates battling for position in this year’s competitive primary. By 7 p.m., when Massachusetts Senator John Kerry arrives more than an hour late for a rally at a Hampton fire hall, organizers are boasting of “another thousand people watching down the road on television.” Kerry’s advance aides direct the overflow crowd to a school gymnasium to watch C-SPAN’s live coverage of the senator’s question-and-answer session.

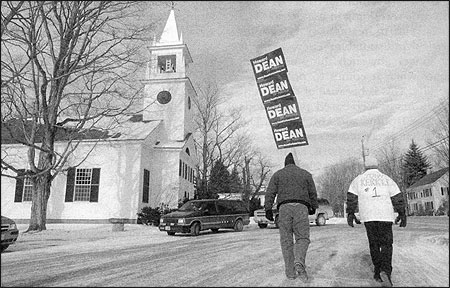

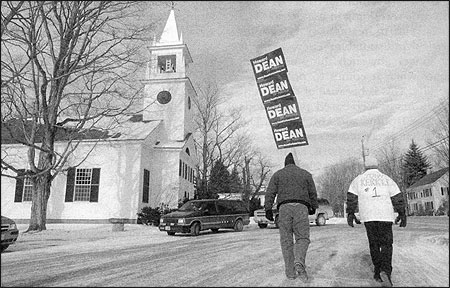

Voters in Salisbury, New Hampshire, were among those who cast votes in the state’s first-in-the-nation primary on January 27, 2004. Residents of Salisbury went to the town hall, which was built in 1839, and votes were collected in a century-old ballot box. Photo by Dan Habib/Concord Monitor.

C-SPAN and the Primary, Then and Now

What has happened to this once-folksy first-in-the-nation primary? C-SPAN’s first foray into New Hampshire was in 1984. It was still the “boys on the bus” generation, when print reporters trailed the candidates, scribbling observations in wire-bound reporters’ notebooks. Cable was the new technology then: We’d been created by the cable television industry in 1979 and CNN, having come along in 1980, was newer still. Back then, C-SPAN’s cameras were often the only ones out in the field, viewed a little skeptically by the likes of longtime political reporters like Jack Germond, David Broder, Mary McGrory, and Roger Simon.

As a nonprofit always looking to conserve operating funds, C-SPAN’s headquarters that year was borrowed space from Manchester’s now defunct Amoskeag National Bank. Our studio control was literally set up in the bank’s telephone hub room. One big-dish satellite uplink was parked for the week in the vacant lot across from the bank, transmitting live studio productions and any candidate events we had recorded that day. Our entire staff for primary week consisted of 18 people.

New Hampshire 2004 for C-SPAN entails a glass-walled studio at the Center of New Hampshire Holiday Inn, a 40-member crew, 12 cameras, a couple of video journalists working with palm-sized digital cameras, three mobile uplink trucks, and the traveling C-SPAN School Bus. And our contingent is dwarfed by the several hundred people at each of the New Hampshire studios of the three broadcast networks, Fox News, CNN and MSNBC. ABC News alone has three “Vote 2004” buses plying Granite State highways uplinking field reports to its news programs.

As C-SPAN’s political editor since 1990, I have overseen the increase in our political troop strength for four presidential cycles. During this week between Iowa and New Hampshire, C-SPAN’s schedule is filled with political programming. Live multi-hour studio productions begin and end each day. Camera crews are dispatched to cover multiple candidate events. The New York Times, in an article published the day before the primary, captured the essence of our approach: Reporter Lynette Clemetson, who interviewed C-SPAN viewers in Miami Beach, wrote that “political junkies can ‘embed’ themselves in campaigns through television vehicles like ‘All Politics Weekend’ on C-SPAN.” For us, this is the culmination of more than three years of New Hampshire campaign coverage. Our first camera crews were dispatched here in January 2001 to follow prospective candidates. It’s just over nine months until the election and already we’ve produced almost 1,000 hours of political programming.

On Tuesday, primary day, I’ll try to make sense of what’s happening here for the 25 University of Denver (DU) students I’m teaching in a course called “Money, Message and the Campaign Process.” It’s a distance learning course, a cooperative project of C-SPAN, DU, and the Denver-based Cable Center, which I teach twice weekly by fiber connect from Washington. This week, we’re using fiber to link the students in Denver with me in New Hampshire. Jack Heath of PrimaryPolitics.com and Craig Crawford of Congressional Quarterly are our guest speakers.

We’ll talk with the students about the societal, political and technological trends that have all conspired to turn this year’s first-in-the-nation primary into a weeklong national media event. Democratic Party chief Terry McAuliffe’s decision to front-load the primaries, combined with a field of seven competitive candidates who have raised and spent millions of dollars, has guaranteed a horserace. Then there are the three all-news cable networks that, in an ongoing battle for ratings, work to outdo one another this year in live event coverage, news reports, and political punditry from and about New Hampshire politicking.

Perhaps most importantly, we’ll talk about the digital revolution, exploding even since the 2000 race. Technology continues to get smaller, better and more affordable, making it possible for hundreds of local, international and alternative media to cover the race right alongside the national media. Inexpensive satellite time now makes it possible for a single correspondent armed with a digital video camera to capture the race for viewers of mid-size and even small TV stations. Increasingly affordable international satellite time, inexpensive cell phone service, and high-speed Internet connections have increased the foreign entourage. And then there’s the Internet itself, which has become a big player in this year’s election, with millions of pages of data on the candidates produced by the campaigns, the conventional media, alternative media, and individuals.

Howard Dean’s exuberant response to the Iowa caucuses demonstrates the speed and influence of the digital revolution: C-SPAN (and others) televised his concession speech live. Soon, the clip of Governor Dean’s now-famous “scream” was airing relentlessly on cable news networks, providing much fodder for the pundits who filled the airwaves before the New Hampshire primary. And just as quickly, creatively edited versions, often set to music, bounced so incessantly around the Web that Governor Dean, in his appeals to supporters, took to citing a Web site (deangoesnuts.com) that collected them all for easy viewing.

For C-SPAN, digital technology is allowing us to cover more candidate events this year with the same sized staff. More events are transmitted live. And events that in past elections were covered with one camera have become switched camera feeds, allowing us to capture more reaction from voters attending the events. Digital streaming and archiving has put all of C-SPAN’s coverage on the Internet allowing anyone—reporters, students, political operatives, interested citizens—to research a candidate’s statements over time.

Our regular telecasts of the candidates’ stump speeches can present new challenges to the campaigners. Witness the undecided voter interviewed live on television after coming in person to hear North Carolina Senator John Edwards campaign. “I already heard this speech twice on C-SPAN,” she announced to the interviewer. “I came here hoping to hear something new.”

How does all of this new intensity affect the campaign? Officials say that voter turnout in New Hampshire this year set a new record. Was it the wider coverage that brought people out to the polls? Craig Crawford believes not, and other political analysts I spoke to agreed. What brings people to the polls, they say, remains much the same as always—an interesting race and effective get-out-the-vote efforts.

The fate of the New Hampshire primary is already being debated, as it seems to be every four years. What the future holds politically and technologically can only be imagined. What we know at C-SPAN is that the continual campaign is a fact of life and the race for 2008 has already begun. Prospecting candidates have already booked themselves in New Hampshire venues later this month. And if the political parties decide that there will be a future for this small state, where politics is a retail game, C-SPAN will be there, as we have been since 1984. In the early days of New Hampshire politics single C-SPAN video journalists with small cameras will ply the small towns, clipping wireless microphones to the lapels of the early contenders as they make appeals to the hardiest of the party faithful, capturing it all for our audience of political junkies long before the media circus comes to town.

Steven Scully is C-SPAN’s political editor and also holds the Amos P. Hostetter chair at the University of Denver, teaching political communications courses via satellite.

The guard at the university’s entrance gate is already bored with the monotony of repeating his directions. “Just follow those cars,” he says, as we crack the window of our rented SUV. Topping the hill, we can see that hundreds of cars already fill the parking spaces, 90 minutes before the start of this morning’s “Women for Dean” rally.

Three satellite trucks are parked outside the University’s Hospitality Center. Inside, the room is elbow-to-elbow and anxious aides have set up an overflow room with a television tuned to C-SPAN, which is also filling up fast. Ultimately, when that room reaches capacity, Dean aides have the unhappy task of turning aside another hundred or so arrivals on this critical final weekend of campaigning.

Equally as impressive as the voters willing to brave the frigid Sunday morning temperatures is the crush of media trailing the former Vermont governor. A dozen television cameras are lined up, aimed at the waiting podium. Our network, C-SPAN, has sent two cameras, a satellite uplink, two producers, an interviewer, and six technicians whose task it is to beam the event live to 80 million C-SPAN homes across the country; to listeners on WCSP, the FM station C-SPAN operates in Washington, and to Web users, who favor the network’s nonstop video stream of political events at C-SPAN.org. We will transmit live for nearly two hours—following Governor Dean through the crowd until the last voter hand is shaken. At this point in the campaign, it is the unscripted interaction between the candidates and voters that brings us our best material.

Governor Dean’s traveling press arrives with the candidate, grumbling about a room unable to fit them. Local police repeatedly clear the hallway of people attempting to jam themselves in the room’s three open doors and threaten to remove still photographers who have climbed on folding chairs at the back of those crowds, angling for a decent shot.

Standing outside, with Governor Dean’s stump speech echoing in the hallway, is a feast for political and media junkies. Republican pollster Frank Luntz circles, looking for a way to circumvent the closed-off access. Newsweek’s Jonathan Alter arrives, spouse and children in tow; MSNBC’s Chris Matthews talks it up with veteran television booker Tammy Haddad, then gets pulled aside for an interview with a Portuguese television crew. (“Not to worry, we have a translator,” he’s told.) A Boston TV anchor leans against the wall, gossiping about station politics with his predecessor, who is on hand to cover the event for the cable network he now works for. A radio reporter from India, tape recorder in hand, is unable to get inside the room and anxiously asks if she can plug her device into C-SPAN’s audio mult box. Numerous individuals are recording the scene with pocket-size video recorders or sending photos home instantly via cell phone.

It is a scene repeated throughout the day and for every one of the top Democratic candidates battling for position in this year’s competitive primary. By 7 p.m., when Massachusetts Senator John Kerry arrives more than an hour late for a rally at a Hampton fire hall, organizers are boasting of “another thousand people watching down the road on television.” Kerry’s advance aides direct the overflow crowd to a school gymnasium to watch C-SPAN’s live coverage of the senator’s question-and-answer session.

Voters in Salisbury, New Hampshire, were among those who cast votes in the state’s first-in-the-nation primary on January 27, 2004. Residents of Salisbury went to the town hall, which was built in 1839, and votes were collected in a century-old ballot box. Photo by Dan Habib/Concord Monitor.

C-SPAN and the Primary, Then and Now

What has happened to this once-folksy first-in-the-nation primary? C-SPAN’s first foray into New Hampshire was in 1984. It was still the “boys on the bus” generation, when print reporters trailed the candidates, scribbling observations in wire-bound reporters’ notebooks. Cable was the new technology then: We’d been created by the cable television industry in 1979 and CNN, having come along in 1980, was newer still. Back then, C-SPAN’s cameras were often the only ones out in the field, viewed a little skeptically by the likes of longtime political reporters like Jack Germond, David Broder, Mary McGrory, and Roger Simon.

As a nonprofit always looking to conserve operating funds, C-SPAN’s headquarters that year was borrowed space from Manchester’s now defunct Amoskeag National Bank. Our studio control was literally set up in the bank’s telephone hub room. One big-dish satellite uplink was parked for the week in the vacant lot across from the bank, transmitting live studio productions and any candidate events we had recorded that day. Our entire staff for primary week consisted of 18 people.

New Hampshire 2004 for C-SPAN entails a glass-walled studio at the Center of New Hampshire Holiday Inn, a 40-member crew, 12 cameras, a couple of video journalists working with palm-sized digital cameras, three mobile uplink trucks, and the traveling C-SPAN School Bus. And our contingent is dwarfed by the several hundred people at each of the New Hampshire studios of the three broadcast networks, Fox News, CNN and MSNBC. ABC News alone has three “Vote 2004” buses plying Granite State highways uplinking field reports to its news programs.

As C-SPAN’s political editor since 1990, I have overseen the increase in our political troop strength for four presidential cycles. During this week between Iowa and New Hampshire, C-SPAN’s schedule is filled with political programming. Live multi-hour studio productions begin and end each day. Camera crews are dispatched to cover multiple candidate events. The New York Times, in an article published the day before the primary, captured the essence of our approach: Reporter Lynette Clemetson, who interviewed C-SPAN viewers in Miami Beach, wrote that “political junkies can ‘embed’ themselves in campaigns through television vehicles like ‘All Politics Weekend’ on C-SPAN.” For us, this is the culmination of more than three years of New Hampshire campaign coverage. Our first camera crews were dispatched here in January 2001 to follow prospective candidates. It’s just over nine months until the election and already we’ve produced almost 1,000 hours of political programming.

On Tuesday, primary day, I’ll try to make sense of what’s happening here for the 25 University of Denver (DU) students I’m teaching in a course called “Money, Message and the Campaign Process.” It’s a distance learning course, a cooperative project of C-SPAN, DU, and the Denver-based Cable Center, which I teach twice weekly by fiber connect from Washington. This week, we’re using fiber to link the students in Denver with me in New Hampshire. Jack Heath of PrimaryPolitics.com and Craig Crawford of Congressional Quarterly are our guest speakers.

We’ll talk with the students about the societal, political and technological trends that have all conspired to turn this year’s first-in-the-nation primary into a weeklong national media event. Democratic Party chief Terry McAuliffe’s decision to front-load the primaries, combined with a field of seven competitive candidates who have raised and spent millions of dollars, has guaranteed a horserace. Then there are the three all-news cable networks that, in an ongoing battle for ratings, work to outdo one another this year in live event coverage, news reports, and political punditry from and about New Hampshire politicking.

Perhaps most importantly, we’ll talk about the digital revolution, exploding even since the 2000 race. Technology continues to get smaller, better and more affordable, making it possible for hundreds of local, international and alternative media to cover the race right alongside the national media. Inexpensive satellite time now makes it possible for a single correspondent armed with a digital video camera to capture the race for viewers of mid-size and even small TV stations. Increasingly affordable international satellite time, inexpensive cell phone service, and high-speed Internet connections have increased the foreign entourage. And then there’s the Internet itself, which has become a big player in this year’s election, with millions of pages of data on the candidates produced by the campaigns, the conventional media, alternative media, and individuals.

Howard Dean’s exuberant response to the Iowa caucuses demonstrates the speed and influence of the digital revolution: C-SPAN (and others) televised his concession speech live. Soon, the clip of Governor Dean’s now-famous “scream” was airing relentlessly on cable news networks, providing much fodder for the pundits who filled the airwaves before the New Hampshire primary. And just as quickly, creatively edited versions, often set to music, bounced so incessantly around the Web that Governor Dean, in his appeals to supporters, took to citing a Web site (deangoesnuts.com) that collected them all for easy viewing.

For C-SPAN, digital technology is allowing us to cover more candidate events this year with the same sized staff. More events are transmitted live. And events that in past elections were covered with one camera have become switched camera feeds, allowing us to capture more reaction from voters attending the events. Digital streaming and archiving has put all of C-SPAN’s coverage on the Internet allowing anyone—reporters, students, political operatives, interested citizens—to research a candidate’s statements over time.

Our regular telecasts of the candidates’ stump speeches can present new challenges to the campaigners. Witness the undecided voter interviewed live on television after coming in person to hear North Carolina Senator John Edwards campaign. “I already heard this speech twice on C-SPAN,” she announced to the interviewer. “I came here hoping to hear something new.”

How does all of this new intensity affect the campaign? Officials say that voter turnout in New Hampshire this year set a new record. Was it the wider coverage that brought people out to the polls? Craig Crawford believes not, and other political analysts I spoke to agreed. What brings people to the polls, they say, remains much the same as always—an interesting race and effective get-out-the-vote efforts.

The fate of the New Hampshire primary is already being debated, as it seems to be every four years. What the future holds politically and technologically can only be imagined. What we know at C-SPAN is that the continual campaign is a fact of life and the race for 2008 has already begun. Prospecting candidates have already booked themselves in New Hampshire venues later this month. And if the political parties decide that there will be a future for this small state, where politics is a retail game, C-SPAN will be there, as we have been since 1984. In the early days of New Hampshire politics single C-SPAN video journalists with small cameras will ply the small towns, clipping wireless microphones to the lapels of the early contenders as they make appeals to the hardiest of the party faithful, capturing it all for our audience of political junkies long before the media circus comes to town.

Steven Scully is C-SPAN’s political editor and also holds the Amos P. Hostetter chair at the University of Denver, teaching political communications courses via satellite.