After 45 years of reporting and writing political news, I’m reading it now at a distance, usually admiring the work of my successors, sometimes grumbling over my coffee about the stories I think are flawed—convinced that I could have done it better. Retirement does that to a newsman—and although at 69 I know it is the turn of another generation of reporters to chronicle campaigns and elections, I still envy them their seats on the bus.

I also gripe when I see obvious errors or read things I consider worthless, as when people identified only as campaign veterans or Democratic managers deliver ponderous statements of the utterly obvious. I saw one of these veterans quoted the other day as saying that the rival Democrats were struggling for early position in an unpredictable contest. Which is to say that they don’t know how it’s going to come out until the voters decide. Some insight.

My daily campaign reading is of The Washington Post, The New York Times, and The Associated Press. I’m biased toward the AP and not only because I spent my professional life there. I prefer copy that is concise and precise. The Times and the Post are encyclopedias of political coverage, often so voluminous that I read in 400 words or so and then start skimming the copy to see if there is anything I need to know buried down there in the 20th paragraph. Usually, I conclude not.

At the same time, though, I am frustrated as a reader when I see stories that cry for background, statistics, history—explanatory touches that put the event of the hour into perspective. Those added words are worth the space and the effort to get the data. It isn’t difficult. Especially with the Internet. Back in my typewriter era, it took time and telephone calls to get background information. Now it takes only a few minutes on a laptop.

Background and explanation is one of the things print can provide that seldom is part of the radio and television coverage. TV does great work on breaking news, and I watch it for that and for the interviews and live events that show readers some of the raw material of political reporting. The nonstop cable outlets prefer to spend much of their time on shout shows and opinionated commentators who don’t want to be bothered with details that might intrude on what they know, which they seem to think is everything. They are entitled to their clamor. I am entitled to ignore it.

Context and Accuracy Matter

Now that I’m out of the action, I can see more clearly the impact of starting-point assumptions on campaign coverage. I read more adjectives than I would have been comfortable writing. Howard Dean’s opponents call him the angry candidate and, in time, the coverage treats that not as an accusation but as a given. I see copy that describes President Bush as a wartime President—just the image the White House wants. You don’t change commanders in chief in the middle of a war. But most days, the war—on terrorism or in Iraq—seems almost incidental to the President’s agenda. Senator John Kerry was tagged as starchy and remote—a stiff, who couldn’t connect with voters. Until he did. As a reader, I wish the coverage would show me how Dean is angrier than his rivals, how Bush is operating as a wartime President, what Kerry was doing that made him stiff. I think the presumptions get in the way of straight reporting.

When images and accusations become part of the campaign shorthand, the coverage suffers. I read a lot on the question of whether Dean is another George McGovern—both antiwar, both considered left of the mainstream. (Curiously, I didn’t read much when McGovern endorsed General Wesley Clark for the nomination.) In fact, McGovern’s overwhelming defeat as the 1972 Democratic nominee had more to do with his shaky economic proposals and his post-convention switch in vice presidential nominees than with his opposition to the Vietnam War.

All of that doesn’t have to be part of the story—but it would be good background to consider when using the “another McGovern” tag. And it certainly ought to be in any story purporting to explore the comparability of the two candidates. The New York Times did such a piece without that part of the background and, worse, with an inaccurate account of one of the episodes that helped McGovern to his nomination: the Edmund S. Muskie crying episode outside The (Manchester) Union Leader before the 1972 New Hampshire primary. The Times’s piece said that Muskie cried as he protested the Union Leader’s publication of a letter denouncing his wife. What’s more, the story went on, the letter turned out to have been written by Nixon operatives.

Wrong, and wrong again. The Union Leader story involved was a reprint of a reprint—a Women’s Wear Daily piece critical of Jane Muskie. Newsweek picked it up, and The Union Leader picked up the magazine version. There was a Nixon dirty tricks letter to The Union Leader about Muskie—but not about his wife.

When I start reading a story and bump up against an error like that, I stop reading. If the writer can’t take the time to check the record and get the facts straight, I won’t take the time to read his or her coverage. Background facts, names and numbers, help make coverage authoritative. I’d like to see more of that, with more precision.

Surfing through cable TV, I came across a Fox News Channel interview with former Senator Eugene McCarthy and stopped to watch the man I covered in 1968. An underline gave background—erroneously noting that McCarthy won the 1968 New Hampshire primary. Fair, balanced and wrong. McCarthy did not win, although he came close enough to show Lyndon Johnson’s vulnerability.

I know that the reporters covering the 2004 campaign have a problem I didn’t face until late in my career. There are simply too many of them, or at least too many people who claim to be covering the story for somebody. It makes legitimate reporting more difficult, and it also distorts the campaign, especially in the early states, Iowa and New Hampshire, where voters like to get up close with their own questions. They seldom can, except by prearrangement, because of the media mob. I don’t know any answer to that one. The only thing worse than having too many people covering or pretending to cover a campaign would be to have some official empowered to say who could and couldn’t be there.

But I fear that the media hoards have become part of the insulation the candidates use, or try to, in order to ward off questions they don’t want asked or answered. Candidates always have tried to put the campaign coverage on their own best terms. They are trying to win, not to illuminate the process. I always accepted that and figured the latter was my job. So I wasn’t outraged when they ducked a hard question—I just pointed it out in print, which is the best comeback we have.

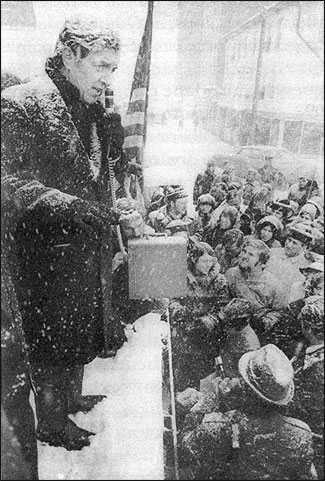

Maine Senator Edmund S. Muskie denounces The (Manchester) Union Leader on February 26, 1972. Photo courtesy of The New York Times.

Connecting Quotes With Names

There are far too many campaign media people quoted in the copy for my taste. In some stories, they get in without being quoted by name—a press secretary for a rival candidate is one construction, a Democratic strategist working for another campaign is another. I wouldn’t use those quotes without a name and campaign address on them. Adam Nagourney of The New York Times got crossways with the Kerry campaign when one of the press secretaries there sent an e-mail attack on a rival, a handout saying it could be attributed only to a spokesman for a Democratic campaign.

Nagourney was right to ignore the attribution note and identify the source—PR people don’t get to make those calls. My rule was that if you want to talk on background, tell me and I’ll decide whether to proceed with the interview or not. For a few days of his campaign in 1964, Barry Goldwater’s people imposed a rule that he couldn’t be quoted, only identified as a source, when he answered questions or made unscripted comments. I was appalled at the number of people in the press who agreed to go along with that. I refused, and the AP spiked a Goldwater story that got Page One play in The New York Times, rather than use it attributed to a source familiar with Goldwater’s views, the outlandish wording the campaign wanted. The Goldwater people soon dropped the whole ruse.

I think of that now when I read a story delivering the opinions of a campaign veteran, or a Democratic manager, or a White House strategist, or any other of the myriad guises in which anonymity appears. It has its place—on matters of fact, not opinions or judgments. I believe in the AP rule: Unattributed material has to be fact, not opinion, it has to be significant news, and it has to be unavailable from any on-the-record source.

I also have a problem with stories that let the press secretaries do the talking the candidates ought to be doing. When I was reporting, what counted was what the candidate said and did, not what his hired hands thought. I see copy now with quotes from campaign spokespeople because they will talk tougher than the candidate will.

When Senator Tom Harkin endorsed Dean in his home state of Iowa, Richard Gephardt’s campaign manager, Steve Murphy, was quoted in The Washington Post as saying Dean was grasping at straws because of the gaffes that showed he was not the best candidate.

Next paragraph: “Gephardt was a bit more restrained, acknowledging that he was disappointed not to get the endorsement ….” Politicians usually want it both ways. I don’t think reporters should help them.

The Expectations Game

These observations don’t even get to the cliché complaint about reporters covering the campaign like a horserace and ignoring the issues. It is a horserace, or at least a race, and the coverage I saw and still see does not ignore the issues. The best of it couples the issues with the race and the candidates, so that you can weave the intensity of the competition together with an account of rival proposals, a combination that keeps readers reading.

One of the most suspect features of what political reporters do is the scorekeeping, the attempt to say who did well short of victory in a presidential primary, where winning isn’t everything. In this election cycle, like so many others, the talking heads on television were trying to set expectations long before the voting began, and so were print analysts, sometimes quoting purported experts—although I don’t think there are any. I never knew anybody who could say reliably that it would be good enough for one candidate or another to run second or third or a close fourth. Not unless the candidate, like Gephardt, said himself that he had to win or come close in Iowa, where his far-back fourth forced him out of the campaign.

My way of handling that part of the story was to keep close track of everything a candidate’s managers said on the record about what they expected to do in a primary. That’s still the expectations game, but now it is based on their expectations, not yours. It’s harder to get the forecasts of the campaigns now that they all know the downside—guess high and the campaign can only lose, guess way low and it won’t be credible. But there are still people in the campaign organizations who will give an honest assessment or blurt a forecast despite the risk to their candidate. One of Muskie’s managers in New Hampshire in 1972 said that if he didn’t get at least 50 percent of the vote, she’d cut her wrists. He didn’t, and she didn’t.

The public opinion polls also are a piece of the expectations game, simply because they set benchmarks. The trouble is that the polls are written in sand, and the next high tide can wash them out. Kerry’s victory in Iowa demonstrated that.

As I read about the polls now and see them built into the coverage, I have to confess to overwriting them sometimes when I was on the job. I tried to be careful and usually was, and the copy I respect now observes that restraint. Too many people put too much stock in them, forgetting that the polls that were supposed to be most reliable, the exit interviews on Election Day 2000, produced the erroneous early call for Al Gore in Florida and, hours later, the premature TV calls for George W. Bush.

As I look back at this, it sounds like the work of an old curmudgeon. I only wish that I were a young curmudgeon, back on the bus and covering 2004.

For all my gripes, I respect and appreciate what the political reporters now are delivering about this crop of candidates. Having been there myself for 11 campaigns, I know how hard it is to accurately and fairly tell readers about the people who want to be President. Today’s solid political reporters are providing what I need to know. I admire what they are doing and, I have to admit, envy their assignment.

Walter Mears reported on national politics for The Associated Press from 1960 to 2001. He received the Pulitzer Prize for national reporting in 1977 for coverage of the 1976 presidential campaign and election. His book, “Deadlines Past: Forty Years of Presidential Campaigning: A Reporter’s Story,” was published in 2003 by Andrews McMeel.

I also gripe when I see obvious errors or read things I consider worthless, as when people identified only as campaign veterans or Democratic managers deliver ponderous statements of the utterly obvious. I saw one of these veterans quoted the other day as saying that the rival Democrats were struggling for early position in an unpredictable contest. Which is to say that they don’t know how it’s going to come out until the voters decide. Some insight.

My daily campaign reading is of The Washington Post, The New York Times, and The Associated Press. I’m biased toward the AP and not only because I spent my professional life there. I prefer copy that is concise and precise. The Times and the Post are encyclopedias of political coverage, often so voluminous that I read in 400 words or so and then start skimming the copy to see if there is anything I need to know buried down there in the 20th paragraph. Usually, I conclude not.

At the same time, though, I am frustrated as a reader when I see stories that cry for background, statistics, history—explanatory touches that put the event of the hour into perspective. Those added words are worth the space and the effort to get the data. It isn’t difficult. Especially with the Internet. Back in my typewriter era, it took time and telephone calls to get background information. Now it takes only a few minutes on a laptop.

Background and explanation is one of the things print can provide that seldom is part of the radio and television coverage. TV does great work on breaking news, and I watch it for that and for the interviews and live events that show readers some of the raw material of political reporting. The nonstop cable outlets prefer to spend much of their time on shout shows and opinionated commentators who don’t want to be bothered with details that might intrude on what they know, which they seem to think is everything. They are entitled to their clamor. I am entitled to ignore it.

Context and Accuracy Matter

Now that I’m out of the action, I can see more clearly the impact of starting-point assumptions on campaign coverage. I read more adjectives than I would have been comfortable writing. Howard Dean’s opponents call him the angry candidate and, in time, the coverage treats that not as an accusation but as a given. I see copy that describes President Bush as a wartime President—just the image the White House wants. You don’t change commanders in chief in the middle of a war. But most days, the war—on terrorism or in Iraq—seems almost incidental to the President’s agenda. Senator John Kerry was tagged as starchy and remote—a stiff, who couldn’t connect with voters. Until he did. As a reader, I wish the coverage would show me how Dean is angrier than his rivals, how Bush is operating as a wartime President, what Kerry was doing that made him stiff. I think the presumptions get in the way of straight reporting.

When images and accusations become part of the campaign shorthand, the coverage suffers. I read a lot on the question of whether Dean is another George McGovern—both antiwar, both considered left of the mainstream. (Curiously, I didn’t read much when McGovern endorsed General Wesley Clark for the nomination.) In fact, McGovern’s overwhelming defeat as the 1972 Democratic nominee had more to do with his shaky economic proposals and his post-convention switch in vice presidential nominees than with his opposition to the Vietnam War.

All of that doesn’t have to be part of the story—but it would be good background to consider when using the “another McGovern” tag. And it certainly ought to be in any story purporting to explore the comparability of the two candidates. The New York Times did such a piece without that part of the background and, worse, with an inaccurate account of one of the episodes that helped McGovern to his nomination: the Edmund S. Muskie crying episode outside The (Manchester) Union Leader before the 1972 New Hampshire primary. The Times’s piece said that Muskie cried as he protested the Union Leader’s publication of a letter denouncing his wife. What’s more, the story went on, the letter turned out to have been written by Nixon operatives.

Wrong, and wrong again. The Union Leader story involved was a reprint of a reprint—a Women’s Wear Daily piece critical of Jane Muskie. Newsweek picked it up, and The Union Leader picked up the magazine version. There was a Nixon dirty tricks letter to The Union Leader about Muskie—but not about his wife.

When I start reading a story and bump up against an error like that, I stop reading. If the writer can’t take the time to check the record and get the facts straight, I won’t take the time to read his or her coverage. Background facts, names and numbers, help make coverage authoritative. I’d like to see more of that, with more precision.

Surfing through cable TV, I came across a Fox News Channel interview with former Senator Eugene McCarthy and stopped to watch the man I covered in 1968. An underline gave background—erroneously noting that McCarthy won the 1968 New Hampshire primary. Fair, balanced and wrong. McCarthy did not win, although he came close enough to show Lyndon Johnson’s vulnerability.

I know that the reporters covering the 2004 campaign have a problem I didn’t face until late in my career. There are simply too many of them, or at least too many people who claim to be covering the story for somebody. It makes legitimate reporting more difficult, and it also distorts the campaign, especially in the early states, Iowa and New Hampshire, where voters like to get up close with their own questions. They seldom can, except by prearrangement, because of the media mob. I don’t know any answer to that one. The only thing worse than having too many people covering or pretending to cover a campaign would be to have some official empowered to say who could and couldn’t be there.

But I fear that the media hoards have become part of the insulation the candidates use, or try to, in order to ward off questions they don’t want asked or answered. Candidates always have tried to put the campaign coverage on their own best terms. They are trying to win, not to illuminate the process. I always accepted that and figured the latter was my job. So I wasn’t outraged when they ducked a hard question—I just pointed it out in print, which is the best comeback we have.

Maine Senator Edmund S. Muskie denounces The (Manchester) Union Leader on February 26, 1972. Photo courtesy of The New York Times.

Connecting Quotes With Names

There are far too many campaign media people quoted in the copy for my taste. In some stories, they get in without being quoted by name—a press secretary for a rival candidate is one construction, a Democratic strategist working for another campaign is another. I wouldn’t use those quotes without a name and campaign address on them. Adam Nagourney of The New York Times got crossways with the Kerry campaign when one of the press secretaries there sent an e-mail attack on a rival, a handout saying it could be attributed only to a spokesman for a Democratic campaign.

Nagourney was right to ignore the attribution note and identify the source—PR people don’t get to make those calls. My rule was that if you want to talk on background, tell me and I’ll decide whether to proceed with the interview or not. For a few days of his campaign in 1964, Barry Goldwater’s people imposed a rule that he couldn’t be quoted, only identified as a source, when he answered questions or made unscripted comments. I was appalled at the number of people in the press who agreed to go along with that. I refused, and the AP spiked a Goldwater story that got Page One play in The New York Times, rather than use it attributed to a source familiar with Goldwater’s views, the outlandish wording the campaign wanted. The Goldwater people soon dropped the whole ruse.

I think of that now when I read a story delivering the opinions of a campaign veteran, or a Democratic manager, or a White House strategist, or any other of the myriad guises in which anonymity appears. It has its place—on matters of fact, not opinions or judgments. I believe in the AP rule: Unattributed material has to be fact, not opinion, it has to be significant news, and it has to be unavailable from any on-the-record source.

I also have a problem with stories that let the press secretaries do the talking the candidates ought to be doing. When I was reporting, what counted was what the candidate said and did, not what his hired hands thought. I see copy now with quotes from campaign spokespeople because they will talk tougher than the candidate will.

When Senator Tom Harkin endorsed Dean in his home state of Iowa, Richard Gephardt’s campaign manager, Steve Murphy, was quoted in The Washington Post as saying Dean was grasping at straws because of the gaffes that showed he was not the best candidate.

Next paragraph: “Gephardt was a bit more restrained, acknowledging that he was disappointed not to get the endorsement ….” Politicians usually want it both ways. I don’t think reporters should help them.

The Expectations Game

These observations don’t even get to the cliché complaint about reporters covering the campaign like a horserace and ignoring the issues. It is a horserace, or at least a race, and the coverage I saw and still see does not ignore the issues. The best of it couples the issues with the race and the candidates, so that you can weave the intensity of the competition together with an account of rival proposals, a combination that keeps readers reading.

One of the most suspect features of what political reporters do is the scorekeeping, the attempt to say who did well short of victory in a presidential primary, where winning isn’t everything. In this election cycle, like so many others, the talking heads on television were trying to set expectations long before the voting began, and so were print analysts, sometimes quoting purported experts—although I don’t think there are any. I never knew anybody who could say reliably that it would be good enough for one candidate or another to run second or third or a close fourth. Not unless the candidate, like Gephardt, said himself that he had to win or come close in Iowa, where his far-back fourth forced him out of the campaign.

My way of handling that part of the story was to keep close track of everything a candidate’s managers said on the record about what they expected to do in a primary. That’s still the expectations game, but now it is based on their expectations, not yours. It’s harder to get the forecasts of the campaigns now that they all know the downside—guess high and the campaign can only lose, guess way low and it won’t be credible. But there are still people in the campaign organizations who will give an honest assessment or blurt a forecast despite the risk to their candidate. One of Muskie’s managers in New Hampshire in 1972 said that if he didn’t get at least 50 percent of the vote, she’d cut her wrists. He didn’t, and she didn’t.

The public opinion polls also are a piece of the expectations game, simply because they set benchmarks. The trouble is that the polls are written in sand, and the next high tide can wash them out. Kerry’s victory in Iowa demonstrated that.

As I read about the polls now and see them built into the coverage, I have to confess to overwriting them sometimes when I was on the job. I tried to be careful and usually was, and the copy I respect now observes that restraint. Too many people put too much stock in them, forgetting that the polls that were supposed to be most reliable, the exit interviews on Election Day 2000, produced the erroneous early call for Al Gore in Florida and, hours later, the premature TV calls for George W. Bush.

As I look back at this, it sounds like the work of an old curmudgeon. I only wish that I were a young curmudgeon, back on the bus and covering 2004.

For all my gripes, I respect and appreciate what the political reporters now are delivering about this crop of candidates. Having been there myself for 11 campaigns, I know how hard it is to accurately and fairly tell readers about the people who want to be President. Today’s solid political reporters are providing what I need to know. I admire what they are doing and, I have to admit, envy their assignment.

Walter Mears reported on national politics for The Associated Press from 1960 to 2001. He received the Pulitzer Prize for national reporting in 1977 for coverage of the 1976 presidential campaign and election. His book, “Deadlines Past: Forty Years of Presidential Campaigning: A Reporter’s Story,” was published in 2003 by Andrews McMeel.