“The Brazil Chronicles” (forthcoming from University of Missouri Press on Nov. 18, 2024) is a mix of memoir and reportage by Stephen G. Bloom, which recounts Rio de Janeiro’s vibrant history as a base for American expat reporters. Fed up with the political and economic turbulence of the 1970s, Bloom, like hundreds of contemporaries, relocated to Brazil, which “held the promise of a new beginning, a place to live out [his] dreams of becoming a newspaper reporter.” What Bloom discovered was a landscape filled with “fellow journalists … who would make their marks on history; others were deadbeats, ne’er-do-wells, grifters, drug runners, CIA agents, and pornographers (and that’s just for starters.)”

This excerpt is about one of America’s most notorious journalists who had a similar sojourn in Brazil: Hunter S. Thompson. Before Thompson refined his gonzo journalism — the first-person, unobjective reporting style that garnered him fame — he was a fledgling journalist struggling to pay the bills while writing his novel, “The Rum Diary,” which would not be published until 1998. Thompson decided to travel to Brazil, which he wrote to a friend, was his last “chance to do something big and bad.” This excerpt has been edited for length.

The idea for Thompson’s tropical peregrination had come through a journalism connection he’d made in his thus-far short-lived newspaper career. In 1961, Thompson had worked with journalist Bob Bone at the Middletown Daily Record in upstate New York. Thompson had the habit of not wearing shoes in the newsroom, which his supervisor did not like, but what got him fired from the newspaper was kicking in a vending machine and destroying it after the offending machine failed to deliver that candy bar that he had paid for. “[H]e just beat it—‘savagely’ to use his word—until it dislodged his candy bar,” recalled Bone.

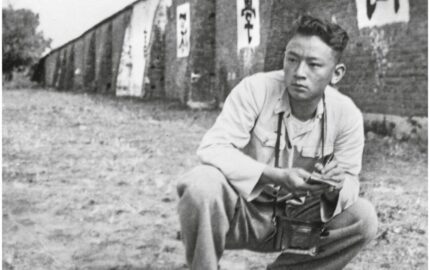

Bone left the Middletown Daily Record soon after Thompson, first going to San Juan, Puerto Rico, then to Brazil for fun, adventure, and a little work, which he found with Bill Williamson’s former employer, the American Chamber of Commerce in Rio, writing the business organization’s magazine, Brazilian Business. Thompson contacted Bone in Rio and asked if he would connect him with Williamson to ask about a job at the Herald. Always on the lookout for American journalists willing to relocate to Brazil on their own dime, Williamson replied with a letter to Thompson that while he couldn’t make any promises, if Thompson showed up at the Herald’s newsroom, Williamson likely would be able to make some use of him. It was the same no-strings commitment Steve Yolen had made to me when he dangled the possibility of a job at the Latin America Daily Post. That was just the opening Thompson had been waiting for. He’d leverage Williamson’s promise of work to reel in other journalistic assignments on the road to Rio, his ultimate destination. That’s what I had done when I connected with the Field News Service to write freelance pieces.

Thompson contacted an at-the-time new, general interest weekly newspaper, the National Observer, published by Dow Jones, where he got a vague commitment, this one for pickup work along the way. Founded by editor Barney Kilgore, who would take the Wall Street Journal from a small, insider’s financial newspaper to a publishing powerhouse, the National Observer would be known for synthesizing events and trends in a stylized and breezy format. An editor at the new weekly, Clifford A. Ridley, wrote back to Thompson, saying he’d consider publishing Thompson’s dispatches from South America. As Williamson had done, Ridley made no promises, but encouraged Thompson to send him any and all of his dispatches. To twenty-four-year-old Thompson, these two quasi-commitments from Williamson and Ridley were more than enough to send him packing.

Thompson would start his southern pilgrimage, like Bone, in Puerto Rico, where he got a job for a soon-to-be insolvent bowling magazine. In San Juan, Thompson would meet William Kennedy, who’d go on to win the 1984 Pulitzer Prize for his masterful novel, Ironweed. At the time, Kennedy was managing editor of another expat English-language newspaper, The San Juan Star, and struggling with his on-the-side fiction writing. Bone had worked at the Star, and Thompson asked Kennedy to hire him at the Star, but Kennedy demurred, saying there wasn’t an opening, but even if there had been, Thompson wouldn’t have been a good fit. Thompson stayed in Puerto Rico for several months, during which he got arrested for his involvement in a brawl prompted by an unpaid bar tab; Kennedy arranged bail to get Thompson sprung from jail.

From Puerto Rico via a roundabout trip to Bermuda, Aruba, and Honduras, Thompson got himself to Bogotá, Colombia. By then, he was a month into what would become a crazed, diarrhetic trek across the northern third of South America. From Lima, Peru, Thompson sent Brazil Herald manager Bill Williamson another letter, inside a wrinkled envelope, which carried the protracted August 3, 1962, dateline: “From the extra bed in the flea-ridden hotel room of Hunter S. Thompson.” The letter advised Williamson, “I will proceed as planned from here to La Paz to Rio . . . . It will involve a mad, headlong poverty-stricken rush across the continent.”

Either Thompson was flexing his unorthodox writing chops or warning Williamson (whom he had never met) that if he ever got to the Herald newsroom, he’d be a resoundingly unconventional hire. It likely was both. Thompson’s scattered correspondence read:

If Rio is no better than the places I have visited thus far I will beat a hasty retreat to the north and write this continent off as a lost cause. For the past month I have felt on the brink of insanity: weakened by dysentery, plagued by fleas and vermin of all sizes, cut off from mail, money, sex and all but the foulest of food and hounded 24 hours a day by thieves, beggars, pimps, fascists, usurers, dolts and human jackdaws of every shape and description. If these are Pizzaro’s ancestors, you are goddamn lucky he never got to Brazil. All this time I have had in the back of my mind an unreasoning certainty that Rio is a decent place where a man can sit in the sun and drink a beer without having to put on a frock coat and carry a truncheon to ward off the citizenry. If this is a delusion I will probably have a breakdown when I arrive and the Embassy will be forced to ship me home like an animal, with “No Dice” scrawled across my passport.

If there ever were a moment in which Gonzo journalism was born, Thompson’s letter to Williamson might have been it. Not scared off by Thompson’s letter, Williamson replied with a positive-but-guarded response: “Show up at the Herald once you get to town.” Williamson was careful not to promise Thompson anything specific. Holed up in Lima, Thompson had just sent off a piece to Ridley at the National Observer (to be headlined, “Democracy Dies in Peru, But Few Seem to Mourn Its Passing”) and was primed for what Thompson had optimistically construed as a firm job offer from. Rio de Janeiro would be the shimmering pot of gold at the end of a thus-far faded South American rainbow.

Thompson arrived in Rio more or less on schedule on Sept. 15, made a beeline for the Herald and met Williamson, who hired him on the spot. In a letter to Ridley at the National Observer, Thompson boasted two days later, “I definitely mean to base here, for a while, anyway. The Brazil Herald offered me a job at a ridiculous salary—adds up to less than $100 a month, U.S.—but I told them I couldn’t tie myself down here with local reporting & still get around enough to send you a varied assortment. I have all intentions of staying here as much as possible, but I want to be free to move around to the other countries as soon as I get rested and cured. It is about time I lived like a human being for a change. . . . This is a fine town & pretty cheap to live in if you’re careful.”

The sentiments seemed spun from A Moveable Feast, in which Hemingway wrote, “In Paris, you could live very well on almost nothing and by skipping meals occasionally and never buying new clothes, you could save and have luxuries.” They were similar to my own upon arriving in São Paulo. What more could a young, eager journalist new to a big foreign city want? During his first week in Rio, Thompson paid a visit to the local AP bureau as a wannabe professional courtesy, which seemed to be his practice when arriving in South American capitals.

Ed Miller, the AP correspondent, remembered meeting Thompson, but not with any affection. “I kicked him out . . . with the blessing of my boss, and he never came back,” Miller recalled. “I honestly can’t remember what it was that pissed me off so much. I think he may have been drunk. I just remember him from that brief visit as being really obnoxious. A complete pain in the ass.”

Thompson was soon joined in Rio by his girlfriend and future first wife, Sandy Conklin. The couple stayed in a budget hotel in Copacabana, and by November had moved to a nearby apartment, which they rented for the equivalent of thirty American dollars a month. Thompson boasted in a letter to a friend that he was thinking of buying a Jeep, having his Doberman flown from his mother’s home in Louisville, and buying a country home on the outskirts of Rio. These were grandiose fictions that Thompson would become famous for. “Right now I have more money than I can reasonably waste. Rio is a hell of a city and impossible to describe in a few lines. I’ll be here another six months, anyway. Same address. Living is cheap but it may not last,” he wrote.

Thompson didn’t do much socializing with other reporters or editors in the Herald newsroom. That might have been because stern Herb Zschech was the newspaper’s editor at the time or that the cliquish staffers were jacks of all trades for whom the Herald was a side gig. Outside of Conklin, Thompson’s only friend in town seemed to have been Bone, the local Chamber of Commerce flack who had connected Thompson to Williamson and the Herald. Bone recalled that while driving along Copacabana Beach one afternoon in an MG convertible, he spotted Thompson loping along Avenida Atlântica, near the Williamson apartment. Bone beeped his horn and Thompson hopped in. “Hunter was a little drunk,” Bone remembered, “but he said, ‘That’s nothing. The thing that’s drunk is in my pocket,’” and proceeded to produce a small monkey to Bone’s amazement.

Thompson and the monkey would become inseparable, so much so that Thompson would take the simian to taverns, although this may be creative fabrication on Bone’s part, a case of one too many monkey-says-to-the-bartender jokes, which Bone imported into his memory, even though Bone steadfastly maintained in his memoir, Fire Bone, that the monkey, whom Thompson named Ace, was actually a coati who was house-broken and washed his hands with soap after using the toilet.

While Thompson’s only newspaper job as a reporter for the Middletown Daily Record had not ended well, his tenure at the freewheeling Brazil Herald turned out to be more conducive to the budding writer’s personality.

Suit-wearing Zschech would characterize hang-loose Thompson in a similar manner as how he had described Herald partner Lee Langley, as “a pre-hippie type,” but would allow that Thompson “turned out some good copy for the Brazil Herald for several months.” To author Brian Kevin, who traced Thompson’s continental odyssey in The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America, Williamson volunteered, “At the time, Hunter was the best reporter we had,” which perhaps said more about the Herald than about Thompson. Williamson would recall that Thompson “smoked a lot, but didn’t drink any more than any other journalist did in those days.” Williamson would also remember that Thompson talked a lot about guns and hunting, but not about drugs.

To [his friend Paul] Semonin, Thompson wrote, “This man seemed to think it was very important that I get my gun in with me and I tend to agree.” As for his life in Rio, Thompson would recall in his 2003 book, Kingdom of Fear, “All things considered, Rio was pretty close to the best place in the world to be lost and stranded when the World finally shuts down.”