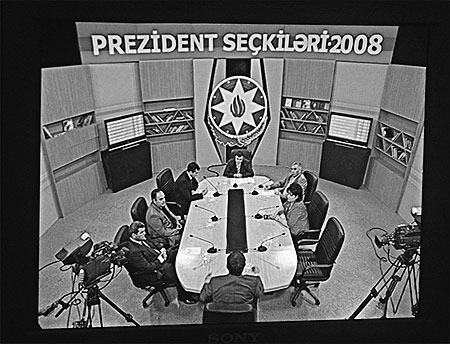

Azerbaijan’s presidential candidates debate on public television.

Fortunately, the 5-hour flight from Heathrow was nearly empty, and I had three seats to get horizontal. I peered out the window and pictured the geopolitical chess board below—Russia, its tanks in Georgia, Armenia and the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh, Iran, a Caspian Sea’s worth of oil and gas, all bordering Azerbaijan. I imagined the travels of Alexander the Great, Marco Polo, and Josef Stalin, across a region that has been conquered and reclaimed for centuries at unfathomable human cost. But from 30,000 feet at midnight, I saw nothing. And as we circled and approached the airport, Baku could have been Salt Lake City. How quickly I learned it was not.

A few months earlier, I would have been at “The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer,” just where I had been for the past 21 years. As senior producer of politics, I witnessed, reported, wrote and produced for television many of the events that shaped America and the world for a generation. The Iran-Contra affair, the Bork and Thomas Supreme Court confirmation hearings, the GOP takeover of Congress, the Democrats take it back, numerous Iraq War resolutions, Monica Lewinsky, and presidential campaigns from “You’re no Jack Kennedy” to “Yes we can.” And I did it for the highest caliber of news programs.

And then I quit. No job. No safety net. A few jaws dropped, but it was time. Past time. Six years removed from my Nieman experience, the urge to be adventurous, to try something different, was still there. But Baku?

Four days after giving notice in May, a friend at the BBC told me the Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy (ADA) was in search of an experienced television producer to create a public affairs program. Some cursory research on Wikipedia and Google maps, and I was fascinated. The ADA recently had been launched by Hafiz Pashayev, Azerbaijan’s first and long-serving ambassador to the United States. His vision was a graduate school of international affairs, one that also would train Azerbaijan’s diplomats to staff embassies around the world, the number of which had doubled to 60 in just the past year. The television program would be an extension of that mission, a forum to encourage open, public discussion and debate of important issues, something that didn’t exist during 70 years under Soviet rule, nor had been tolerated much in Azerbaijan in the two decades since.

I had my concerns. The ADA was an arm of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The ministry spokesperson would be our host. Censorship immediately crossed my mind. And on my first day of work, Ambassador Pashayev warned me there were people in the government who would be suspicious of what we were trying to do. But would I ever again get an opportunity like this? I knew I could only hope to begin to open a few eyes and minds in Azerbaijan, while limited to issues of regional and international importance, not domestic. Still, the chance to start something revolutionary in this frontier democracy had me feeling a little like Thomas Jefferson, maybe with a dash of 007! I agreed to give it three months.

Baku is not the exotic land I had imagined. It’s no longer the desired destination of Silk Road merchants. This is a hard city someone once described as a cross between Marseilles and Jersey City. But while most of the world slips into recession, Azerbaijan is in the midst of a second “energy boom.” Oil and gas deposits are fueling one of the fastest-growing GDPs on the planet, and the money is being spent. Baku, with its history and charm, is being rebuilt at a dizzying pace, replacing Soviet-era housing with European architecture first introduced by oil barons more than a century ago. Seventeen years after declaring independence, Azerbaijan is on a fast track of capitalism, as if it’s making up for lost time.

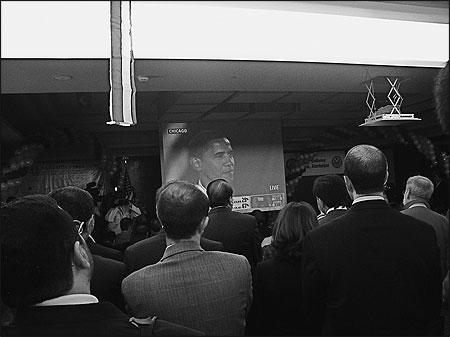

But Azerbaijan has not fully embraced democracy. While the government shows intentions of shedding its label as one of the world’s “most corrupt,” the people aren’t demanding it. The recent presidential campaign received almost no news media coverage. Opposition candidates used free, but not prime, air time on public television to talk past each other, while incumbent President Ilham Aliyev, the son of the former president, ignored them all. International monitors did give Election Day officials improved marks for their transparency, but this was no contest. Aliyev was re-elected with nearly 90 percent of the vote and few seemed to care. In Azerbaijan, there was infinitely more interest in President-Elect Obama.

There appears to be a high degree of news self-censorship in Baku, especially among the broadcast media. For the most part, television reporters don’t have the training, nor have experienced the practices, that are second nature to my colleagues in the United States. Production values are poor and sloppy. Lead stories on newscasts often are lengthy ribbon-cutting ceremonies or presidential declarations. There are few stories about life in Baku. Nothing is bad, nothing is wrong, nothing is challenged. The only villain is Armenia.

But because of my association with the foreign ministry, I believed I was in a position to effect change from the inside. All doors began to open. All seven Baku television stations bid to become our “technical” partners. I selected Azerbaijan’s public television network, which is flush with money. Its director agreed to give us all the technicians, equipment and facilities we needed to produce our program, plus a Sunday evening time slot. We agreed to give them top-quality analytical programming, the content of which they could not edit.

But no one at the ADA had any television experience. They were busy creating a university. However, everyone at the academy speaks English, the language of diplomats. So my two young, part-time assistants translated “TV” as I haggled with Azeri TV engineers and Turkish architects at the construction site that was to become our set location. We covered every detail—where to place cameras, how much lighting, what about the acoustics, creating animation and graphics, selecting music. We made room for a small audience. And we decided to call the program “Majlis,” an ancient Persian term for a room where important issues are discussed in a relaxed setting. That led us to a dozen furniture showrooms where we sampled sofas and overstuffed chairs in everything from Italian contemporary leather to “desert chic.”

Meanwhile, I became immersed in “pipeline politics.” Transporting oil and gas from the South Caucasus is determined as much by diplomacy as by science. The Russia-Georgia conflict in August disrupted energy flows, and the pipelines nearly were bombed out of commission. It rattled nerves throughout Europe and Central Asia and became the key issue at a multination energy summit in Baku in mid-November. That also determined the schedule for the first ADA “Majlis.” In preparation, I studied oil routes from Baku to the Black Sea and Mediterranean, researched and located energy analysts in Istanbul, Tblisi, Vilnius and Kiev. And we sent out a dozen invitations to energy ministers from Poland to Italy. For 20 years, my arena stretched between the two ends of Pennsylvania Avenue. Suddenly, the playing field had become so much bigger.

One month before our airdate, I learned construction on our new set would not be completed. We scrambled looking at hotel conference rooms, museums and theaters, and were thrilled to be offered the century-old Ismailiyya mansion, the Presidium of the National Academy of Sciences. We only locked in our ministers on the day of their summit meeting in Baku and taped immediately after. C. Boyden Gray from the U.S. delegation cancelled at the last moment, but ministers from Greece, Georgia, Lithuania, Ukraine and Azerbaijan appeared, stressing the importance of “energy security” without ever mentioning Russia by name. However, two of the energy analysts I selected for the following panel were rejected by the senior ADA staff—one because he taught at a university with a religious affiliation, another because he wrote for a “radical” news agency. I blanched. Should I immediately take the journalistic “high road” back to Washington? “Better not to give suspicious ones reason to complain on the first program,” it was explained to me. I said nothing. And so, we selected a “safe” panel, and the discussion suffered. In fact, we heard stronger voices from our audience. But to the viewers, the telecast looked rich. The illuminated Ismailiyya was magnificent, and the program was technically flawless. We heard comments like “intellectual,” “sincere,” “different.” It was a good beginning for the ADA.

Two days later, as I pack for a flight back to the United States, I wonder if “Majlis” will make a difference, where my colleagues will take it, if it will encourage a more aggressive news media in Baku, an open press. But that doesn’t appear to be a priority at this stage of Azerbaijan’s development. This is a deeply scared country. Twenty years ago, Azerbaijan was the first of the Soviet republics to begin a “freedom movement,” and Soviet troops exacted great revenge. War with Armenia killed tens of thousands, with nearly a million refugees. Today, however, Azerbaijan is cashing in. There is a strong feeling of nationalism. Flags, and images of the presidents, current and former, are everywhere. Democracy, on the other hand, may take time to develop. While the United States is pruning after 230 years, Azerbaijan is still trying to push the pillars into place.

Aynura, Gunay and Khazar, the ADA “Majlis” part-time staff. Photo by James Trengrove.

The U.S. Embassy in Baku hosts a breakfast to watch the election returns. Photo by James Trengrove.

James Trengrove, a 2002 Nieman Fellow, was senior producer for politics and congressional reporting for “The News Hour with Jim Lehrer” for 21 years before resigning this summer. The program “Majlis” can be viewed, in Azeri.