In late September 2008, a California state appeals court struck down a gag order that forbade The Orange County Register to report by “all means and manner of communication, whether in person, electronic, through audio or video recording, or print medium” testimony by any witness appearing in a class action wage-and-hour suit brought by its newspaper carriers.

The trial judge—whose ruling was overturned—had concluded that the injunction was necessary to prevent future witnesses from being influenced by others’ testimony. But this gag order violated just about every precedent establishing the strong presumption against prior restraints going all the way back to 1931’s Near v. Minnesota and 1971’s Pentagon Papers case, New York Times v. United States. As the appellate panel ruled, there was no way that the risk that witnesses in this civil case might be influenced by news reports was sufficient to justify this kind of censorship. Other, less restrictive alternatives—such as simply admonishing the witnesses not to read the paper—would accomplish the same goal.

Was this appeals court’s ruling a great victory for freedom of the press? Well, yes and no. Yes, because the appeals court got it right. But no, because the trial judge thought his order was the right thing to do, despite nearly 70 years of unbroken precedent to the contrary.

Unfortunately, that trial judge is not alone in seeming to be First Amendment-challenged. It’s not that they hate the press, exactly. But they don’t really understand the unique role the news media play in a democratic society. They reject the idea that “the press” should enjoy any special privileges. Nor do they seem to know what to do about those legions of unidentified and ungovernable bloggers and other online journalists out there who, in their eyes, do little except spread false rumors, violate copyright laws, and identify rape victims with impunity, all the time hiding behind the anonymity that the Web permits. As a consequence, courts and legislatures, reluctant to apply different rules to the “old” and “new” media, are rethinking the basic constitutional principles that have protected a free press for generations.

Web Restrictions

The Orange County Register case is similar to recent examples of judges issuing gag or “take down” orders against Web site operators who have had the temerity to report details about Paris Hilton’s personal life or the names and statistics of Major League Baseball players without authorization from the league. The difference is that some of these orders have actually been upheld. Although in the past it was accepted law in the United States that the remedy for invasion of privacy was to sue for damages, not enjoin the speech, for many judges the immediacy and ubiquity of publishing on the Internet changes the balance, justifying more draconian measures.

Copyright law presents a slightly different challenge. The owners of intellectual property have always had the legal right to demand that violators “cease and desist” publishing and distributing infringing works. But the advent of the Internet means that copying others’ work without permission is easier than ever before. Congress enacted the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) in 1998 to address this situation without also stifling protected speech. As an incentive to encourage Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to continue to offer untrammeled access to the Web, the DMCA’s “safe harbor” provision protects them from liability when their subscribers upload infringing material, as long as they “act expeditiously” to remove the material once notified that it has been posted.

The problem is that a prudent ISP will be inclined to take down the content and leave the subscriber and the copyright owner to sort out their respective rights later. To facilitate that process, the DMCA permits copyright holders to use “administrative subpoenas” to compel the ISP to disclose the identity of the subscriber. Although the subpoenas are supposed to be strictly limited to curtailing infringing activity, they can also be used to circumvent well-established First Amendment principles protecting the right to engage in anonymous speech.

A similar threat arises in the context of defamatory publications. Many bloggers and other posters engage in vituperative commentary online without identifying themselves. In a provision similar to the DMCA safe harbor, section 230 of the Communications Decency Act grants ISPs immunity from liability for libelous speech posted by their subscribers. But again, the ISP can be compelled to reveal the individual’s identity if a judge concludes that a plaintiff has a valid claim. Those who might be affected by this ruling include newspapers and other media, which could be forced to unmask readers who post anonymous comments on their Web sites, leaving them vulnerable to retaliation or retribution.

Confidential Sources

The question of whether journalists should have the right to protect their confidential sources is being affected by the Internet, too. The existence and extent of any reporter’s privilege has been an unsettled and volatile issue in the courts ever since the Supreme Court’s narrow decision in Branzburg v. Hayes in 1972 determined that the First Amendment did not create one. Despite that opinion, however, most states and federal circuits recognized some kind of protection, at least in certain circumstances. But after a series of rulings to the contrary in several influential federal appeals courts, most notably in the recent Judith Miller case, media groups lobbied Congress to pass a federal shield law. Although attracting bipartisan support, the bill remains stalled in the Senate.

A major point of contention with this legislation is the question of how to determine who would be covered by the law. Attempts to adopt a broad functional definition to include anyone who is “doing journalism,” regardless of medium or platform, was rejected by those who feared the law would be used to protect individuals “linked to terrorists or other criminals,” or who are merely “casual bloggers,” presumably unbound by traditional ethical standards and accountable to no one.

Whether existing shield laws in the states will cover bloggers and other nonmainstream journalists remains an open question and very much depends on the particular statutory language and the courts’ interpretation of it. Although a California court ruled that the state shield law protected the identities of operators of a blog that revealed Apple Computer’s trade secrets on the ground that their publications constituted “news,” the Ninth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals refused to recognize that blogger and self-described anarchist Josh Wolf was a journalist under the same law, because he was not “connected with or employed by” a news organization.

RELATED WEB LINK

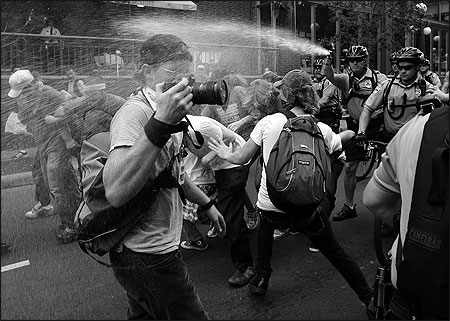

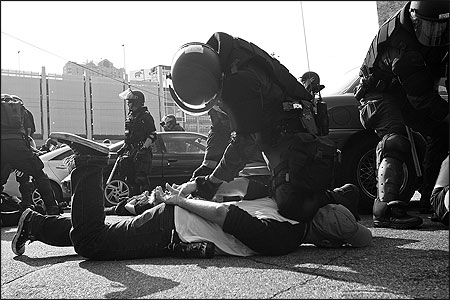

Watch the YouTube video about Amy Goodman’s arrest »Law enforcement officials at the Republican National Convention in September 2008 collectively threw up their hands and declined to make a distinction, detaining or arresting dozens of journalists, both “mainstream” and “citizen,” swept up while attempting to cover and report on the demonstrations and protests in Saint Paul. Of course, the Internet made possible “real-time” and worldwide distribution of reports of the protests.

Digital technology has facilitated newsgathering in many ways. But its impact has not been entirely positive. For example, in theory, the digitization of government records, coupled with the ability of anyone with a computer and a modem to gain easy access to them, should have been celebrated as a welcome opportunity for meaningful citizen oversight. But judges and legislators, driven by fear that such access would facilitate illegal conduct ranging from identity theft to employment discrimination, have used the threat of it to justify curtailing access to these electronic files.

It doesn’t stop there. Judges also cite their discomfort at the idea that someone logging on from a distant location, having no “legitimate interest” in the local community, will amuse himself by trawling through court or real estate records and publishing them online. They worry that citizen journalists with cell phone cameras will invade courtrooms and post trial footage online, a practice they consider both disruptive and undignified. Although they might support the concept of access to government records and proceedings in the abstract, once it becomes cheap and easy the gatekeepers began to question its wisdom. Information, it seems, is just too valuable—or too dangerous—to entrust to a blogger.

None of these considerations should drive legal policy. Rights of access, or freedom of expression, are not, and should not be, conditioned on some government official’s idea of what constitutes “responsible” journalism. Judges and legislators should continue to follow the principles that have protected the press, and the public’s right to know, for more than 200 years. But at the same time, those who publish in the new media and are always quick to invoke the First Amendment are challenging so many things held sacred.

The question confronting all of us—given the tenor of our times and the judicial decision-making we are seeing—is whether the First Amendment will survive this challenge.

Jane Kirtley has been the Silha Professor of Media Ethics and Law at the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Minnesota since August 1999. Prior to that, she was executive director of The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press in Arlington, Virginia, for 14 years.