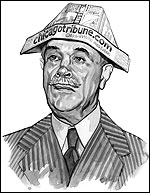

Meet “The Colonel.” He’s a pretty dapper guy. In his early 50’s, he has worked for the Chicago Tribune and lived in the city his whole life—well, except for that stint in the Army Reserves. That’s how he earned his nickname. He started out as a copy boy in the newsroom, worked his way up, and now he’s Web ambassador for chicagotribune.com.

Because he spends so much time at the Tribune, he lives in the South Loop, close to Soldier Field and his beloved Bears. The Colonel is adventurous, and he makes his way around the city to try all sorts of different foods. He loves eating steak at Gibson’s outdoor cafe and is not above heading over to Jim’s Original for a Polish.

While he’s a Web guy, the Colonel starts his day off with a cup of Stewart’s coffee and the papers. He’ll check out chicagotribune.com and suntimes.com for local news, then he’ll scan nytimes.com and latimes.com. After his daily news fix, he watches the latest viral videos on YouTube.

The Colonel is very interested in local politics, and he’s a take-things-one-issue-at-a-time moderate. His news tastes are reflected in what he shares with his friends. He makes a point to interact with Tribune readers individually, but he’ll do this, too, on Facebook, Twitter, Digg and other social media sites and blogs.

“I’m here to make the most of your time,” he says. “My goal is never to send out a link that’s lame.”

The Colonel doesn’t exist. Or does he?

Roughly 40 percent of the traffic arrives at chicagotribune.com when a user types our URL into a browser or goes to a bookmarked page.

The other 60 percent? That traffic comes via search engines, Web sites, and blogs. On a typical day in early 2008, Google was our No. 1 source of outside traffic, followed by Yahoo! (#2), CareerBuilder (#3), Fark (#10), The New York Times (#20), and Facebook (#47). In all, more than 4,000 sites sent users our way—with 350,000 different clicks.

At chicagotribune.com, a lot of our time is spent focused on our content, as it should be. But given those percentages, we needed to be asking whether another very important job we have is to make sure our content finds an audience and connects with people in other areas of the Web.

That question led to our “Project O.” The “O” was for search-engine and social media optimization and for Owen—as in Owen Youngman, the Chicago Tribune vice president who championed and funded the group tasked with spreading our content to the rest of the Web.

Social Media’s Viral Power

RELATED WEB LINK

"Texas youth justice"

-www.chicagotribune

.com/parisTexas youth justiceFor me, Project O’s genesis occurred in March 2007. Back then, I was the former sports editor at the Tribune who’d been working as associate editor for innovation for just a few months. Tribune national correspondent Howard Witt wrote a piece about Paris, Texas, a small town with a troubled history. Published on March 12th—and available online that same day—Witt’s story attracted 16,000 page views. The next day, the count dropped to 1,300. But on March 21st, nine days after it appeared on the newspaper’s front page, this story about a tiny place far from Chicago generated 43,300 page views. By the end of March, this story was our site’s most popular story, with more than 126,000 people coming to chicagotribune.com to read it.

What happened? Turns out that more than 300 blogs had linked to the story, and it became popular on Digg, where stories are submitted by users and then promoted to the home page based on the rankings of users. Roughly 35,000 page views of the total came from people who went directly from Digg to our Web site to take a look at this story.

That was my first experience with Digg and the viral power of social media. And it made a lasting impression. It forced me to think about how the Tribune and other newspapers produce so many great stories—a lot of them with remarkable images—and yet, in the typhoon of information, I wondered how people can find ones they might not know exist but will be drawn to read once they do. And how might we be able to help make this happen. Clearly this question went beyond searching online, since I doubt many people set out in March to pop the words “Paris, Texas” into their search engine.

I knew then that there was an active role for us to play in doing a better job of bringing what Tribune reporters work hard to produce to the attention of new and appreciative audiences. And we had to take the material to these audiences, wherever they are finding and learning from each other on the Internet. Then we had to somehow connect the material we had with people who might be interested in taking a look. To do this, our job would be to construct cyberconnections that, when acted on, would mirror the serendipitous reading experience familiar to so many as they thumb through pages of a newspaper. What made this a bit different, however, is that we needed to figure out how to do this systematically, rather than relying on luck and happenstance.

Colonel Tribune Goes Social

It was Saint Patrick’s Day, 2008, and Daniel Honigman and I were sitting in my office. Honigman was the first of the four 20-somethings I hired for Project O. He quit a full-time job and signed on to this project for $500 a week, no benefits, and no guarantees beyond the 12 weeks that the Tribune had approved to fund this project.

We had no handbook to follow, nor anyone inside the company to whom we could turn for advice. We weren’t even sure whether a mainstream news site could become part of the cybercommunities that evolve from social media sites. But Honigman had impressed me several months earlier with a story he’d written about the importance of influencers to corporations and his abiding interest in social media and search-engine optimization.

In addition to using Google Trends, which tracks and reflects what keywords people are searching for on a daily basis, we decided to start by focusing on a few social media sites—Facebook, Twitter, Fark, Reddit and Digg. I was concerned about having Daniel and the three others I hired—Amanda Maurer, Erin Osmon, and Christina Antonopoulos—use their own Facebook profiles to represent the Tribune. Daniel suggested we create an online avatar, and that’s how “Colonel Tribune,” a nod to the newspaper’s legendary figure, Col. Robert McCormick, was born.

I know what you are thinking. How could you pick an old white guy with a military title to be the Tribune’s ambassador in the world of new media? Believe it. The Colonel has taken on a life of his own though Twitter and other social media sites where he can be found. He routinely gets news tips from some readers, hears from others about corrections and typos in stories, and he is offered story ideas. One example: The Colonel was notified via Twitter about a bomb threat and building evacuation downtown. The tip was checked out by a reporter, and the story was posted on chicagotribune.com.

Through Twitter and Facebook, we’ve invited people to meet-ups at a local bar. They showed up in numbers that surprised us—and even paid homage to the Colonel by wearing his trademark hat.

The goal for Project O was one million page views a month. By June, at its peak, it was doing more than six times that number. And so our project continues with permanent funding.

Can a mainstream news site become part of the social media scene? Absolutely, yes. But be warned. To do this requires having the same kind of great team I had: Facebook-savvy youth, an innovative Web staff, and an extremely supportive newsroom. Even then, it will be essential to become immersed in the various communities and to reach out in ways that create interactive relationships. Like friendships, these are ones that come only with time, trust and hard work.

For us, we had a Colonel to help.

Bill Adee is editor of digital media for the Chicago Tribune.

Because he spends so much time at the Tribune, he lives in the South Loop, close to Soldier Field and his beloved Bears. The Colonel is adventurous, and he makes his way around the city to try all sorts of different foods. He loves eating steak at Gibson’s outdoor cafe and is not above heading over to Jim’s Original for a Polish.

While he’s a Web guy, the Colonel starts his day off with a cup of Stewart’s coffee and the papers. He’ll check out chicagotribune.com and suntimes.com for local news, then he’ll scan nytimes.com and latimes.com. After his daily news fix, he watches the latest viral videos on YouTube.

The Colonel is very interested in local politics, and he’s a take-things-one-issue-at-a-time moderate. His news tastes are reflected in what he shares with his friends. He makes a point to interact with Tribune readers individually, but he’ll do this, too, on Facebook, Twitter, Digg and other social media sites and blogs.

“I’m here to make the most of your time,” he says. “My goal is never to send out a link that’s lame.”

The Colonel doesn’t exist. Or does he?

Roughly 40 percent of the traffic arrives at chicagotribune.com when a user types our URL into a browser or goes to a bookmarked page.

The other 60 percent? That traffic comes via search engines, Web sites, and blogs. On a typical day in early 2008, Google was our No. 1 source of outside traffic, followed by Yahoo! (#2), CareerBuilder (#3), Fark (#10), The New York Times (#20), and Facebook (#47). In all, more than 4,000 sites sent users our way—with 350,000 different clicks.

At chicagotribune.com, a lot of our time is spent focused on our content, as it should be. But given those percentages, we needed to be asking whether another very important job we have is to make sure our content finds an audience and connects with people in other areas of the Web.

That question led to our “Project O.” The “O” was for search-engine and social media optimization and for Owen—as in Owen Youngman, the Chicago Tribune vice president who championed and funded the group tasked with spreading our content to the rest of the Web.

Social Media’s Viral Power

RELATED WEB LINK

"Texas youth justice"

-www.chicagotribune

.com/parisTexas youth justiceFor me, Project O’s genesis occurred in March 2007. Back then, I was the former sports editor at the Tribune who’d been working as associate editor for innovation for just a few months. Tribune national correspondent Howard Witt wrote a piece about Paris, Texas, a small town with a troubled history. Published on March 12th—and available online that same day—Witt’s story attracted 16,000 page views. The next day, the count dropped to 1,300. But on March 21st, nine days after it appeared on the newspaper’s front page, this story about a tiny place far from Chicago generated 43,300 page views. By the end of March, this story was our site’s most popular story, with more than 126,000 people coming to chicagotribune.com to read it.

What happened? Turns out that more than 300 blogs had linked to the story, and it became popular on Digg, where stories are submitted by users and then promoted to the home page based on the rankings of users. Roughly 35,000 page views of the total came from people who went directly from Digg to our Web site to take a look at this story.

That was my first experience with Digg and the viral power of social media. And it made a lasting impression. It forced me to think about how the Tribune and other newspapers produce so many great stories—a lot of them with remarkable images—and yet, in the typhoon of information, I wondered how people can find ones they might not know exist but will be drawn to read once they do. And how might we be able to help make this happen. Clearly this question went beyond searching online, since I doubt many people set out in March to pop the words “Paris, Texas” into their search engine.

I knew then that there was an active role for us to play in doing a better job of bringing what Tribune reporters work hard to produce to the attention of new and appreciative audiences. And we had to take the material to these audiences, wherever they are finding and learning from each other on the Internet. Then we had to somehow connect the material we had with people who might be interested in taking a look. To do this, our job would be to construct cyberconnections that, when acted on, would mirror the serendipitous reading experience familiar to so many as they thumb through pages of a newspaper. What made this a bit different, however, is that we needed to figure out how to do this systematically, rather than relying on luck and happenstance.

Colonel Tribune Goes Social

It was Saint Patrick’s Day, 2008, and Daniel Honigman and I were sitting in my office. Honigman was the first of the four 20-somethings I hired for Project O. He quit a full-time job and signed on to this project for $500 a week, no benefits, and no guarantees beyond the 12 weeks that the Tribune had approved to fund this project.

We had no handbook to follow, nor anyone inside the company to whom we could turn for advice. We weren’t even sure whether a mainstream news site could become part of the cybercommunities that evolve from social media sites. But Honigman had impressed me several months earlier with a story he’d written about the importance of influencers to corporations and his abiding interest in social media and search-engine optimization.

In addition to using Google Trends, which tracks and reflects what keywords people are searching for on a daily basis, we decided to start by focusing on a few social media sites—Facebook, Twitter, Fark, Reddit and Digg. I was concerned about having Daniel and the three others I hired—Amanda Maurer, Erin Osmon, and Christina Antonopoulos—use their own Facebook profiles to represent the Tribune. Daniel suggested we create an online avatar, and that’s how “Colonel Tribune,” a nod to the newspaper’s legendary figure, Col. Robert McCormick, was born.

I know what you are thinking. How could you pick an old white guy with a military title to be the Tribune’s ambassador in the world of new media? Believe it. The Colonel has taken on a life of his own though Twitter and other social media sites where he can be found. He routinely gets news tips from some readers, hears from others about corrections and typos in stories, and he is offered story ideas. One example: The Colonel was notified via Twitter about a bomb threat and building evacuation downtown. The tip was checked out by a reporter, and the story was posted on chicagotribune.com.

Through Twitter and Facebook, we’ve invited people to meet-ups at a local bar. They showed up in numbers that surprised us—and even paid homage to the Colonel by wearing his trademark hat.

The goal for Project O was one million page views a month. By June, at its peak, it was doing more than six times that number. And so our project continues with permanent funding.

Can a mainstream news site become part of the social media scene? Absolutely, yes. But be warned. To do this requires having the same kind of great team I had: Facebook-savvy youth, an innovative Web staff, and an extremely supportive newsroom. Even then, it will be essential to become immersed in the various communities and to reach out in ways that create interactive relationships. Like friendships, these are ones that come only with time, trust and hard work.

For us, we had a Colonel to help.

Bill Adee is editor of digital media for the Chicago Tribune.