RELATED WEB LINK

"How Digital Natives Experience News"

- John PalfreyIn his book, “Born Digital: Understanding the First Generation of Digital Natives,” John Palfrey, who codirects Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society, observes how “grazing digital natives” read a headline or at most a paragraph with little or no context. Only those who take a “deep dive” into the content will end up making sense of the news.

Based on the rapidity of digital change we’ve experienced during the past decade, the news audience of 2019—and the technology they use—will be very different. What we can depend on, however, is that those raised with digital technology will represent the majority in that audience. So if Palfrey’s observations accurately describe the audience of the future, this “expedition” that all of us are taking will benefit from understanding how digital natives now use media for entertainment, information, education and social networking.

Admittedly, the map to guide us is crude. But it is reasonable to believe that the digital natives are leading the way—and are way ahead of news organizations. This belief is based on three predictable phases when new technology is adopted:

Digital natives who download iTunes on iPhones and blog about YouTube on MySpace are in the third phase. At the same time, if conferences such as the Online News Association held in September are accurate indicators, the industry is perhaps at the threshold of phase two. More print reporters are learning video, TV reporters are starting to blog, and professors are teaching new skills to communicate with an audience that values shorter, fact-driven multimedia.

All of these efforts address the formidable challenge for journalists to provide future news users with information relevant to them. In short, an industry in phase two still delivers most of its content on pages of text with links. Meanwhile, digital natives know what they want, how to find it (or even produce it), and whether it’s worth their time.

Consider a future news model—one that integrates research by educators and psychologists with what we know about journalism to propose four concepts of value to digital natives. Online, we can already find plenty of examples of such concepts, but it is from this combination that research suggests the most effective way to attract and retain the news audience of the future. The problem, as confirmed by a recent study from The Associated Press, is that readers are “overloaded with facts and updates” and “having trouble moving deeply into the background and resolution of news stories.”

Since 1998, the Lab for Communicating Complexity Online has been investigating how younger audiences process various types of news and formats. Measuring the “usability” of a Web site or tracking eye movements on a Web page can be valuable, but the lab uses a wider lens to focus on broader media behaviors and audience preferences.

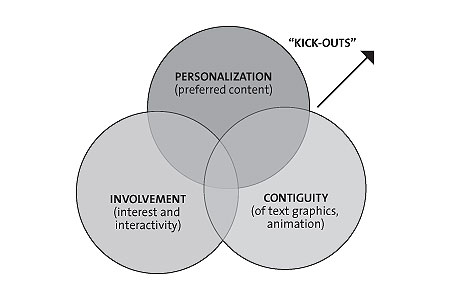

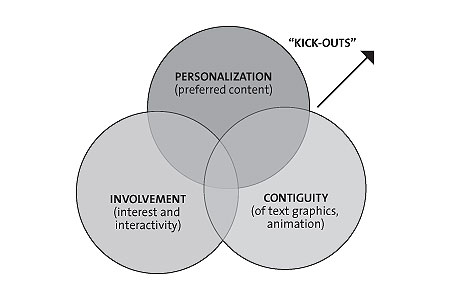

Preliminary results tell us that it requires more than efficient aggregation of news to satisfy a savvy audience that interacts with video games and personalized social networks. The PICK news model, shown in the diagram on page 15 of three overlapping concepts, synthesizes what we know about personalization, involvement and contiguity (or coherence) in news with minimal distractions, which we refer to as cognitive “kick-outs.”

Here’s some good news: These PICK concepts have nothing to do with abandoning core principles of clear, accurate, ethical journalism and, in fact, have everything to do with strengthening them. Like news told in print, multimedia stories also must be organized, coherent and easy to understand. To make these stories engaging and informative, however, will require that additional skills be identified, learned and consistently practiced by the journalists of the future.

Also, the PICK model does not consider “multimedia” to be just video or a slideshow on a Web page. Neither does it pertain to long-form journalism for which an audience has the motivation and time to focus on an issue of interest. PICK defines multimedia as an environment (i.e. a full page or entire Web site) where multiple elements—hypertext, video, slideshows, blogs, forums, graphics and animation—are presented with text and personalized to the user.

Personalizing the News

In general, personalization is about the extent to which a user can choose content congruent with his or her interests. Researchers at Pennsylvania State University confirm that personalization generates more positive attitudes—especially from more experienced users—than generic pages of content. And positive attitudes enhance the audience’s perceived relevance and novelty of the content. Interestingly, merely manipulating the level of choice, however, does not generate positive attitudes if the content is judged to be only “mediocre.”

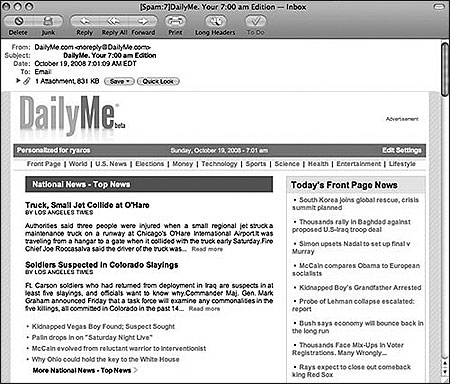

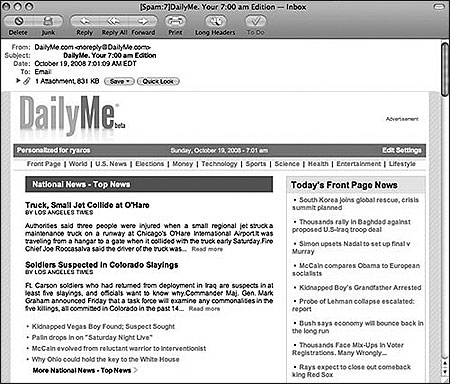

Today, Google News allows users to customize their own news page. And DailyMe.com e-mails a summary of news from preferred categories that link to the original stories. On Poynter’s E-Media Tidbits, Northwestern Professor Rich Gordon recently wrote about the start-up company e-Me Ventures, which is developing technology to store all of the content collected by journalists or submitted by a community. This could help producers of news to assemble content most likely to be relevant to individual users.

But how much personalization will future audiences expect?

AUTHOR'S NOTE

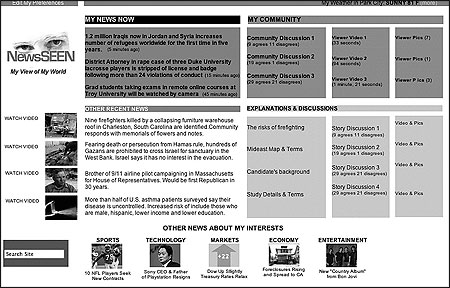

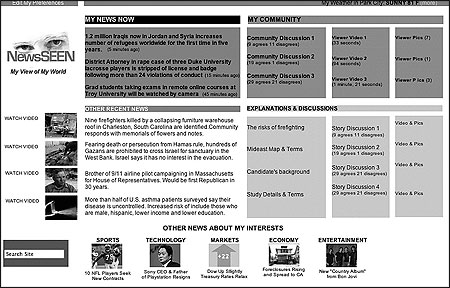

News in categories that the user rates as “secondary” in interest appear lower on the page, with the national and international stories sandwiched in between. Less familiar news and complex topics, such as those about health, science and the economy, are supported by more “explanatory” video, graphics and focused discussion.PICK’s concept of personalization takes us farther through a prototype called “NewsSEEN.” The prototype not only provides news of interest, but it prioritizes news by level of interest. It also presents news with informative “explanatory headlines” and marries preferred news with online communities that have shared interests. Then members of these communities engage in focused discussions about the issues. In this way, NewsSEEN tests how professionally produced, personalized content (or PPP) can be combined with, yet differentiated from, citizen-produced content.

NewsSEEN is receiving stellar reviews from our study’s students, because the format addresses many of their interests in more personalized and interactive ways than anything else available.

There are also opportunities for more personalized graphics. At the International Symposium on Online Journalism, Professor Alberto Cairo from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill presented examples of how databases linked to interactive Flash graphics—ones that users can manipulate—significantly enhance user involvement and engagement with the story. Designing the right interactive graphic, therefore, can be an art in itself.

Involvement

By involvement, we mean the degree to which users input choices and/or content. Education research tells us that more interactivity breeds more involvement. And more involvement means greater attention paid to content. But the level of involvement varies. Clicking a “play” button for a one-minute video represents much less involvement than reading a few sentences, choosing steps in a related animation, selecting a 10-second video, and then posting comments about the story. The problem is that too much involvement inhibits comprehension when interactivity overwhelms a user’s cognition, a complaint we hear often from the current online audience. More research will identify the point at which too much interactivity becomes counterproductive.

Contiguity

A Web page might look appealing, but research in the United Kingdom tells us that users take approximately 50 milliseconds to form an opinion about a page. Contiguity in multimedia is how the elements of hypertext, photos, animation, slides, links, blogs, video and audio, all combine to communicate one coherent message. Our published studies show that even subtle variations in the structures of news text and links produce significant differences in audience interest ratings and their understanding of stories. Researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara found that users generate nearly 50 percent more creative solutions to problems when different forms of explanations are fully integrated. Without coherence in multimedia content, users do what most content producers hope to avoid—they terminate their engagement. The PICK model calls this terminated engagement a “kick-out.”

Kick-Outs

The goal is nothing new. Grab the audience with effective headlines, photos, video and formats. The PICK model argues that the attention-deficit digital world—with its overwhelming amount of information—requires communicators to now be more aware of things that frequently terminate audience attention. These are controllable “kick-outs.” The most obvious kick-out is a broken link, but others include too much text, lengthy video, pop-up windows, unfamiliar terms, confusing graphics, or interactive animation that’s too complex. Of course, it’s impossible to eliminate every potential kick-out but, as the grazing digital audience continues to grow, so will the need for critical assessment of how news is presented online and ways to eliminate avoidable kick-outs.

Where Does This Path Lead?

Ultimately, the challenge is how to simultaneously combine effective techniques of personalization, involvement, contiguity and minimal kick-outs with clear, accurate, ethical journalism. Addressing this complexity when producing and delivering news will actually simplify how the audience will then engage with the content. But to do this well will require that news reporters, editors and videographers join with producers, educators and students to more clearly understand how digital natives process information differently than any previous audience has. Does a slideshow or video need to be that long? What is too long? Is the video or graphic redundant with information already in the accompanying text? How does one person’s interest lead to engagement with a community that shares that interest?

These questions—and so many more—frame the mission of our exploration.

It might be reasonable to conclude that the PICK model is still too abstract for immediate application. To some extent, the technology needed to support NewsSEEN has yet to be developed. In the interim, indications are that those avoiding exploration of the new territory risk being abandoned by a restless audience of digital natives—an audience that appears to already know the territory into which all of us are headed.

Ronald A. Yaros is an assistant professor in the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland and director of the Lab for Communicating Complexity With Multimedia. A former president of an educational software corporation for 10 years, he combines nearly 20 years in electronic journalism, a PhD from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and a Master’s in education to research news audiences and new media. Details of this research can be viewed at: www.merrill.umd.edu/ronyaros/.

"How Digital Natives Experience News"

- John PalfreyIn his book, “Born Digital: Understanding the First Generation of Digital Natives,” John Palfrey, who codirects Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society, observes how “grazing digital natives” read a headline or at most a paragraph with little or no context. Only those who take a “deep dive” into the content will end up making sense of the news.

Based on the rapidity of digital change we’ve experienced during the past decade, the news audience of 2019—and the technology they use—will be very different. What we can depend on, however, is that those raised with digital technology will represent the majority in that audience. So if Palfrey’s observations accurately describe the audience of the future, this “expedition” that all of us are taking will benefit from understanding how digital natives now use media for entertainment, information, education and social networking.

Admittedly, the map to guide us is crude. But it is reasonable to believe that the digital natives are leading the way—and are way ahead of news organizations. This belief is based on three predictable phases when new technology is adopted:

- Awareness and exploration of the new technological tools

- Learning how to use the new tools

- Applying these new tools to daily life.

Digital natives who download iTunes on iPhones and blog about YouTube on MySpace are in the third phase. At the same time, if conferences such as the Online News Association held in September are accurate indicators, the industry is perhaps at the threshold of phase two. More print reporters are learning video, TV reporters are starting to blog, and professors are teaching new skills to communicate with an audience that values shorter, fact-driven multimedia.

All of these efforts address the formidable challenge for journalists to provide future news users with information relevant to them. In short, an industry in phase two still delivers most of its content on pages of text with links. Meanwhile, digital natives know what they want, how to find it (or even produce it), and whether it’s worth their time.

Consider a future news model—one that integrates research by educators and psychologists with what we know about journalism to propose four concepts of value to digital natives. Online, we can already find plenty of examples of such concepts, but it is from this combination that research suggests the most effective way to attract and retain the news audience of the future. The problem, as confirmed by a recent study from The Associated Press, is that readers are “overloaded with facts and updates” and “having trouble moving deeply into the background and resolution of news stories.”

Since 1998, the Lab for Communicating Complexity Online has been investigating how younger audiences process various types of news and formats. Measuring the “usability” of a Web site or tracking eye movements on a Web page can be valuable, but the lab uses a wider lens to focus on broader media behaviors and audience preferences.

Preliminary results tell us that it requires more than efficient aggregation of news to satisfy a savvy audience that interacts with video games and personalized social networks. The PICK news model, shown in the diagram on page 15 of three overlapping concepts, synthesizes what we know about personalization, involvement and contiguity (or coherence) in news with minimal distractions, which we refer to as cognitive “kick-outs.”

Here’s some good news: These PICK concepts have nothing to do with abandoning core principles of clear, accurate, ethical journalism and, in fact, have everything to do with strengthening them. Like news told in print, multimedia stories also must be organized, coherent and easy to understand. To make these stories engaging and informative, however, will require that additional skills be identified, learned and consistently practiced by the journalists of the future.

Also, the PICK model does not consider “multimedia” to be just video or a slideshow on a Web page. Neither does it pertain to long-form journalism for which an audience has the motivation and time to focus on an issue of interest. PICK defines multimedia as an environment (i.e. a full page or entire Web site) where multiple elements—hypertext, video, slideshows, blogs, forums, graphics and animation—are presented with text and personalized to the user.

Personalizing the News

In general, personalization is about the extent to which a user can choose content congruent with his or her interests. Researchers at Pennsylvania State University confirm that personalization generates more positive attitudes—especially from more experienced users—than generic pages of content. And positive attitudes enhance the audience’s perceived relevance and novelty of the content. Interestingly, merely manipulating the level of choice, however, does not generate positive attitudes if the content is judged to be only “mediocre.”

Today, Google News allows users to customize their own news page. And DailyMe.com e-mails a summary of news from preferred categories that link to the original stories. On Poynter’s E-Media Tidbits, Northwestern Professor Rich Gordon recently wrote about the start-up company e-Me Ventures, which is developing technology to store all of the content collected by journalists or submitted by a community. This could help producers of news to assemble content most likely to be relevant to individual users.

But how much personalization will future audiences expect?

AUTHOR'S NOTE

News in categories that the user rates as “secondary” in interest appear lower on the page, with the national and international stories sandwiched in between. Less familiar news and complex topics, such as those about health, science and the economy, are supported by more “explanatory” video, graphics and focused discussion.PICK’s concept of personalization takes us farther through a prototype called “NewsSEEN.” The prototype not only provides news of interest, but it prioritizes news by level of interest. It also presents news with informative “explanatory headlines” and marries preferred news with online communities that have shared interests. Then members of these communities engage in focused discussions about the issues. In this way, NewsSEEN tests how professionally produced, personalized content (or PPP) can be combined with, yet differentiated from, citizen-produced content.

NewsSEEN is receiving stellar reviews from our study’s students, because the format addresses many of their interests in more personalized and interactive ways than anything else available.

There are also opportunities for more personalized graphics. At the International Symposium on Online Journalism, Professor Alberto Cairo from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill presented examples of how databases linked to interactive Flash graphics—ones that users can manipulate—significantly enhance user involvement and engagement with the story. Designing the right interactive graphic, therefore, can be an art in itself.

Involvement

By involvement, we mean the degree to which users input choices and/or content. Education research tells us that more interactivity breeds more involvement. And more involvement means greater attention paid to content. But the level of involvement varies. Clicking a “play” button for a one-minute video represents much less involvement than reading a few sentences, choosing steps in a related animation, selecting a 10-second video, and then posting comments about the story. The problem is that too much involvement inhibits comprehension when interactivity overwhelms a user’s cognition, a complaint we hear often from the current online audience. More research will identify the point at which too much interactivity becomes counterproductive.

Contiguity

A Web page might look appealing, but research in the United Kingdom tells us that users take approximately 50 milliseconds to form an opinion about a page. Contiguity in multimedia is how the elements of hypertext, photos, animation, slides, links, blogs, video and audio, all combine to communicate one coherent message. Our published studies show that even subtle variations in the structures of news text and links produce significant differences in audience interest ratings and their understanding of stories. Researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara found that users generate nearly 50 percent more creative solutions to problems when different forms of explanations are fully integrated. Without coherence in multimedia content, users do what most content producers hope to avoid—they terminate their engagement. The PICK model calls this terminated engagement a “kick-out.”

Kick-Outs

The goal is nothing new. Grab the audience with effective headlines, photos, video and formats. The PICK model argues that the attention-deficit digital world—with its overwhelming amount of information—requires communicators to now be more aware of things that frequently terminate audience attention. These are controllable “kick-outs.” The most obvious kick-out is a broken link, but others include too much text, lengthy video, pop-up windows, unfamiliar terms, confusing graphics, or interactive animation that’s too complex. Of course, it’s impossible to eliminate every potential kick-out but, as the grazing digital audience continues to grow, so will the need for critical assessment of how news is presented online and ways to eliminate avoidable kick-outs.

Where Does This Path Lead?

Ultimately, the challenge is how to simultaneously combine effective techniques of personalization, involvement, contiguity and minimal kick-outs with clear, accurate, ethical journalism. Addressing this complexity when producing and delivering news will actually simplify how the audience will then engage with the content. But to do this well will require that news reporters, editors and videographers join with producers, educators and students to more clearly understand how digital natives process information differently than any previous audience has. Does a slideshow or video need to be that long? What is too long? Is the video or graphic redundant with information already in the accompanying text? How does one person’s interest lead to engagement with a community that shares that interest?

These questions—and so many more—frame the mission of our exploration.

It might be reasonable to conclude that the PICK model is still too abstract for immediate application. To some extent, the technology needed to support NewsSEEN has yet to be developed. In the interim, indications are that those avoiding exploration of the new territory risk being abandoned by a restless audience of digital natives—an audience that appears to already know the territory into which all of us are headed.

Ronald A. Yaros is an assistant professor in the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland and director of the Lab for Communicating Complexity With Multimedia. A former president of an educational software corporation for 10 years, he combines nearly 20 years in electronic journalism, a PhD from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and a Master’s in education to research news audiences and new media. Details of this research can be viewed at: www.merrill.umd.edu/ronyaros/.