There has been a murder in the newsroom. An office secretary at the fictional New York Globe has discovered the body of one Theodore S. Ratnoff.

Ratnoff’s eyes were closed. His face looked peaceful. But there, in the center of his chest, was a four-inch-wide green hunk of metal. She recognized it immediately. It was the base of an editor’s spike, used in the old days to kill stories. The metal shaft protruding from it was sunk into Ratnoff’s blue-and-red-striped shirt, hammered in so hard that it had created a tiny cavity filled with bright blood. The end of his red tie dipped into it, like a tongue into a martini glass. Fixed to the spike was a note.

She leaned over the body to read it. It was in purple ink.

It said, simply: “Nice. Who?”

RELATED WEB LINK

Author John Darnton talks about the demise of good journalism.

- Chicago ReaderJohn Darnton’s novel “Black & White and Dead All Over” may be a roman á clef for those steeped in the world of New York newspapering. I suppose a Big Apple media watcher might recognize Darnton’s twisted characters in the city’s real world newspaper journalists. But to a West Coaster who has never worked in New York, the novel is strictly metaphor.

It’s not just an editor who has been killed, but old-time newspapering, maybe even the newspaper. How appropriate the metaphorical weapon is an old lead spike. So the question, “Who killed Ratnoff?,” could as easily be “Who is killing (or has killed) newspapers?”

Darnton’s answer to both questions is the same: Malevolent corporate tycoons, greedy and devious publishers, self-promoting editors, hack reporters, and assorted other hangers-on who have forgotten the values of their craft in order to pursue their own interests.

There are heroes in Darnton’s world. The dogged young investigative reporter who unravels the mystery is a newspaper archetype. So is his buddy, the in-the-cups veteran reporter whose world-weary cynicism can’t disguise both talent and commitment. And the traditionalist managing editor seems to command some level of respect from journalists who think he has at least some integrity.

But the real hero, in the end, is a young computer whiz who saves the day by taking his newspaper online to break the big story.

How is that for metaphor?

Blogging About the Past

RELATED WEB LINK

Read Smith’s July 31, 2008 blog entry »For me, Darnton’s newspaper murder mystery came along at just the right time. Some months back, foreseeing the massive layoffs coming to my newspaper, The Spokesman-Review in Spokane, Washington, I posted on my “News is a Conversation” blog an essay titled “Still a Newspaperman.”

I wrote it late one night after a particularly dismal day at the office when it appeared as if all of my efforts to stave off budgetary disaster had come to nothing. It was intended as a quiet meditation on the sort of newspapering I knew when I was first coming into the business in the early 1970’s. Of course my reminiscence was rose-colored. The newspaper world of 1973 had its own problems, from a less rigorous ethical framework to blatant sexism to dull and lifeless stenographic reporting.

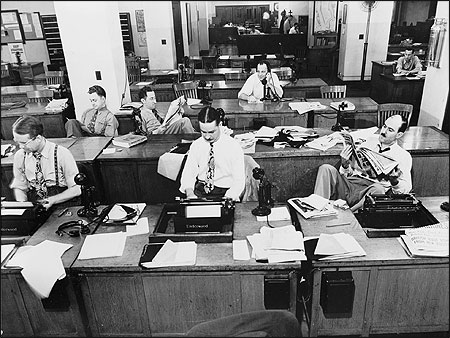

But it was a good time, too. Newspaper journalism was vital to our democratic systems, to our communities. Newspaper journalists were (mostly) credible, even respected. And newsrooms were fun places. Smoke- filled, loud, profane, busy. Newspapering was fun even when the journalism was hard, maybe most fun when it was hardest.

Darnton remembers those days. His fictional New York Globe is a throwback in almost every way except for the rank incompetence that seems to be killing it. The characters are stereotypes, certainly. But their like, for good or ill, could, in my early years, be found in every American newsroom.

In Darnton’s book, investigative reporter Jude Hurley solves the murder mystery with the help of a young computer whiz who may be the Globe’s new owner. I would guess that Darnton saw this as an optimistic conclusion, the marriage of shoe-leather newspapering and online publishing saving both the Globe and the day.

That marriage may yet prove successful. Newspapers, as with the Globe, will continue, almost certainly, in some form. But in real life it’s an imperfect ending. As newsroom after newsroom eviscerates its staff, losing veteran journalists with their connections to an important past, the generations-old foundation of American newspapering erodes further, perhaps beyond the point of no return. And it’s not just institutional and craft memory that is being lost.

We’re losing a sense of our purpose, our mission, our values. Those of us older than a certain age learned those things from our mentors, the great generation of journalists who walked up the hill from train stations all over the country in 1945 and ’46 to take jobs at newspapers big and small. But this generation’s mentors are leaving before their job is done, and those who are left, young and old, are so busy fighting for their professional lives—while trying to stay ahead of light-speed technological change—they have little time to think of journalism beyond today’s deadline.

I now think that was why there was a palpable sadness permeating my elegy to the past.

Response to my blog posting was astonishing. I received hundreds of e-mails, letters, phone calls, and blog comments from all over the world. It’s fair to say the majority came from journalists of my generation who saw something of their own experiences in my writing. But I also heard from younger journalists who argued it was time for the oldsters to move on, to leave the field for those who know more about computers, mobile devices, social networking, and other journalistic tools of the 21st century. Some suggested I was living in the past and, by staying there, I had become irrelevant to our industry’s future.

It was a fascinating debate, with the sides defined by generation and experience.

After all of that, I remain convinced that our profession is losing something, something important to our craft and the citizens we are called to serve. It is not a disservice to our future to understand that.

At the end of Darnton’s book, the surviving Globe journalists gather in a bar (where else?) to talk about the paper’s future. With the veterans is Clive, the Web-savvy whiz kid who now owns the paper. As Darnton describes it, the lively gathering degenerates into “a round of inebriated, hopelessly optimistic proposals.”

Let’s get back to our roots, get back to the basics. Afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted. That’s the motto.

Let’s be who we are. Let’s stop trying to be everything to everybody and just tell it straight.

Let’s get back to hard news, do hard-hitting investigations.

Let’s swagger a little. Let’s be brave again.

Let’s dump the ombudsman!

By Christ, print’s not dead yet!

Jude watched Clive’s face. At one point, he heard him mutter, almost to himself, “Some of that, yes. But not all. We can’t go back. The Internet is here to stay and we have to adjust to it.”

Read another article by Smith—about his engagement of younger reporters in transforming the newsroom »We have no choice in the matter. We must adjust to young Clive’s world.

But don’t tell me I can’t cry a bit over the loss of mine.

Steven A. Smith was, until October 1st, 2008, editor of The Spokesman-Review in Spokane, Washington. His blog is stillanewspaperman.com.