In their new book, “The Infodemic: How Censorship and Lies Made the World Sicker and Less Free,” published by Columbia Global Reports on April 26, Robert Mahoney and Joel Simon argue that the coronavirus is not the only public health crisis of the past two years. With the Covid-19 pandemic arose a twin “infodemic,” in which lies, distortions, and misinformation undermined the global response to a disease that has killed millions. Mahoney and Simon examine how governments — like those in China, Russia, Brazil, and the U.S. under President Donald Trump — censored critical information about the pandemic to their advantage, wielding misinformation to consolidate power.

The following excerpt analyzes how local news offered communities access to reliable information during the pandemic, and how their loss allows misinformation to flourish:

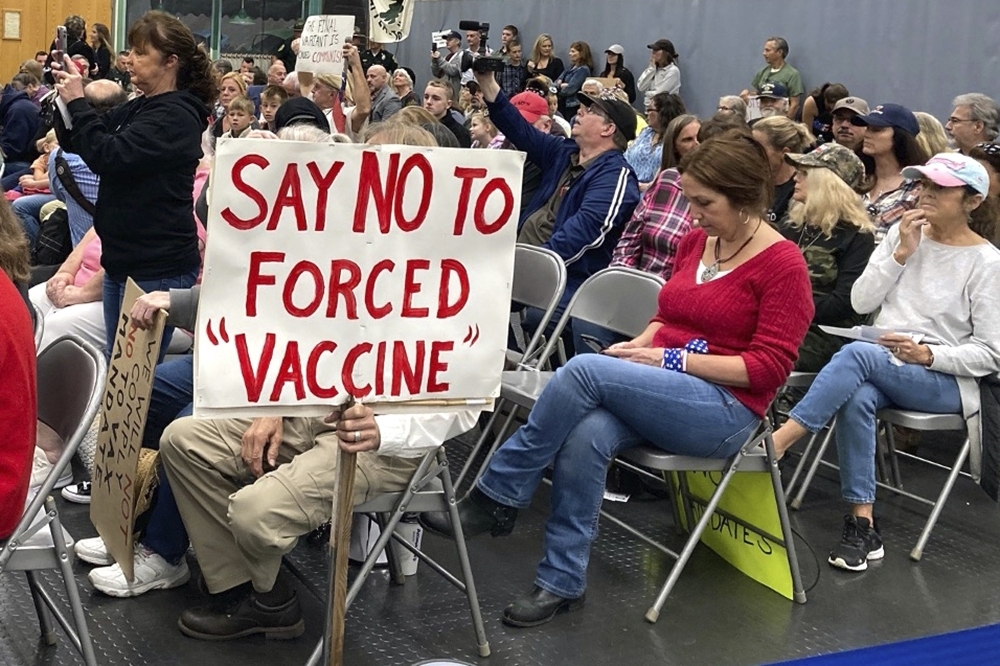

The wasting away of local news outlets had created a vacuum that platforms peddling misinformation or lies were quick to fill. Around the world, social media-fueled political polarization and misinformation engendered what the World Health Organization called an “infodemic.” In many countries, misleading information and conspiracy theories sparked heated public debates about the severity of the disease, death rates, and the efficacy of preventative measures like social distancing and mask-wearing. National media then amplified these debates. Social media platforms, with their opaque algorithms tailoring content to keep users online and in front of ads, fanned the flames. In their business model, fear and anger breed engagement. Locked down at home for months on end, people were already spending an average of 50 percent more time on screens and so were easy prey in their self-selected echo chambers for outrage-inducing opinion and clickbait, as well as government-orchestrated misinformation campaigns.

In the era of YouTube and Facebook, journalists are no longer the privileged gatekeepers of information. In any event, nearly half the people online do not get their information from recognized news sites but from social media, friends, family, and interest groups both online and offline. Tech companies pledged to clamp down on inaccurate COVID information but their platforms were awash in it. Citizens trying to wade through this morass of misinformation needed a local press that served not only as a conduit of accurate news but as a watchdog. The loss of local newspapers’ shoe-leather reporting meant less scrutiny of officials and their actions (or sometimes inactions) in fighting the disease. Social media is full of content, but Google and Facebook don’t send news crews into hospitals’ COVID intensive-care units or pay reporters to wait for hours outside of local government offices and legislatures in the hope of buttonholing an official or lawmaker.

Despite the financial carnage, it is print publishers who still employ the bulk of reporters in the US and many other leading media markets and invest in news gathering. The US Bureau of Labor statistics in 2016 showed print employing the majority of reporting staff, with broadcasters accounting for about 25 percent and online media 10 percent. In the UK, the corresponding figures were 69 percent, 10 percent, and just 1 percent from digital media, according to Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, head of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford.

Local news outlets and the staff or freelancers they employ are often the source of investigations and breaking news that broadcasters and digital sites then pick up and amplify. “When the real information people were seeking was about closures in their area, school closures, mask mandates, essential workers, local, state, and national relief funds, they turned to local news providers,” said Rebecca Frank, vice president of research with the News Media Alliance, which represents about 2,000 newspapers in the US. “News providers have never been more valuable to consumers and yet these news companies, because of the way that advertising has changed . . . have been doing that work for less compensation.”

The following excerpt analyzes how local news offered communities access to reliable information during the pandemic, and how their loss allows misinformation to flourish:

The wasting away of local news outlets had created a vacuum that platforms peddling misinformation or lies were quick to fill. Around the world, social media-fueled political polarization and misinformation engendered what the World Health Organization called an “infodemic.” In many countries, misleading information and conspiracy theories sparked heated public debates about the severity of the disease, death rates, and the efficacy of preventative measures like social distancing and mask-wearing. National media then amplified these debates. Social media platforms, with their opaque algorithms tailoring content to keep users online and in front of ads, fanned the flames. In their business model, fear and anger breed engagement. Locked down at home for months on end, people were already spending an average of 50 percent more time on screens and so were easy prey in their self-selected echo chambers for outrage-inducing opinion and clickbait, as well as government-orchestrated misinformation campaigns.

In the era of YouTube and Facebook, journalists are no longer the privileged gatekeepers of information. In any event, nearly half the people online do not get their information from recognized news sites but from social media, friends, family, and interest groups both online and offline. Tech companies pledged to clamp down on inaccurate COVID information but their platforms were awash in it. Citizens trying to wade through this morass of misinformation needed a local press that served not only as a conduit of accurate news but as a watchdog. The loss of local newspapers’ shoe-leather reporting meant less scrutiny of officials and their actions (or sometimes inactions) in fighting the disease. Social media is full of content, but Google and Facebook don’t send news crews into hospitals’ COVID intensive-care units or pay reporters to wait for hours outside of local government offices and legislatures in the hope of buttonholing an official or lawmaker.

Despite the financial carnage, it is print publishers who still employ the bulk of reporters in the US and many other leading media markets and invest in news gathering. The US Bureau of Labor statistics in 2016 showed print employing the majority of reporting staff, with broadcasters accounting for about 25 percent and online media 10 percent. In the UK, the corresponding figures were 69 percent, 10 percent, and just 1 percent from digital media, according to Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, head of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford.

Local news outlets and the staff or freelancers they employ are often the source of investigations and breaking news that broadcasters and digital sites then pick up and amplify. “When the real information people were seeking was about closures in their area, school closures, mask mandates, essential workers, local, state, and national relief funds, they turned to local news providers,” said Rebecca Frank, vice president of research with the News Media Alliance, which represents about 2,000 newspapers in the US. “News providers have never been more valuable to consumers and yet these news companies, because of the way that advertising has changed . . . have been doing that work for less compensation.”