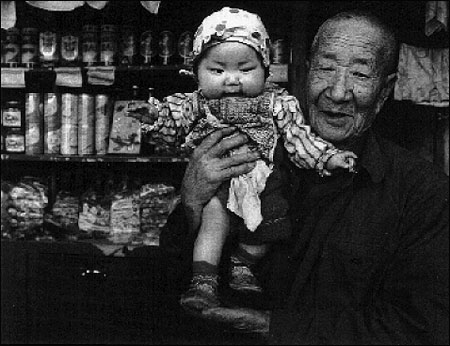

Photo by Stan Grossfeld, 1992 Nieman Fellow, The Boston Globe.

[This article originally appeared in the Spring 1992 issue of Nieman Reports.]

Professor Wu’s son opened the door a crack and peered into the concrete hallway with a worried frown. “My father isn’t home,” he said curtly. As I turned to leave, he added, “Don’t bother coming back.” Later I wished the professor’s son had softened his remark with a plea for understanding, but on that stuffy day in July 1989 he didn’t have to.

People’s Liberation Army troops had mowed down unarmed demonstrators around Tiananmen Square just weeks earlier. Despite his advanced age, Professor Wu—who asked that his full name not be used for fear of reprisals—had spoken out in support of students’ demands for a more open political system. The last thing Wu’s family wanted was a Western journalist at the door, much less the questioning by undercover police likely to follow.

Reporter’s Dilemma Never Changed

In the two and a half years since the crackdown, the visceral fear of foreign reporters expressed by the professor’s son and many other Chinese has given way to a calm and often ironic wariness, but my dilemma as a reporter never changed. Should I continue to see Chinese friends and sources when I knew I was being followed? Or did the fact that my contacts were only questioned after our meetings, not arrested, mean I could shrug off the unrelenting presence of security agents?

Armed with clumsily concealed walkie-talkies and hidden cameras, undercover police from China’s Ministry of State Security, the country’s KGB, have continued to monitor and harass foreign correspondents and their Chinese friends and acquaintances since 1989. Some Chinese have received warnings in person, along with friendly encouragement to inform on their reporter contacts. Others are monitored more subtly, hearing through friends or colleagues of ominous visits by security agents to their work units. Two friends of mine learned from sympathetic coworkers that undercover police had come to inspect their dossiers, or dangan, the personal files kept on every Chinese citizen.

Trip to Sichuan Filmed By Police

Obsessive monitoring of foreign correspondents in China reaches beyond the boundaries of Beijing. Permission to cover outlying regions must be granted by local authorities, who take pains to steer foreign journalists toward showcase villages and enterprises and away from poorer districts. Authorities routinely deny the foreign press access to Tibet and to China’s impoverished regions. When local Foreign Affairs bureaus grant permission to visit, the trip may be subject to monitoring by police apparently operating under their own set of orders. Undercover police tailed and videotaped two American reporters during a March 1990 visit to Chongqing, the industrial heart of central Sichuan province, for no discernible reason. A plainclothes policeman even filmed the reporters as they emerged from an innocuous scheduled interview with city officials at Chongqing’s light industry bureau.

Within Beijing, constant surveillance has a maddening effect. I was tailed for a year and a half, from June 1990 until my departure in early November 1991. The apparent aim was to thwart the process of gathering news and to silence dissent, and the techniques employed were frustratingly effective.

I wasn’t able to ignore the police, despite the professed indifference of the majority of my Chinese friends. “It’s nothing,” scoffed one Beijing intellectual after seeing me to the door and discovering two plainclothes police in long leather overcoats lurking outside his apartment block, muttering theatrically into walkie-talkies.

Other acquaintances were less cavalier. Older Chinese who bore the scars of the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution asked with evident embarrassment if we could meet less often. A few people stopped calling altogether.

Some took to using cryptic aliases over the telephone, which clearly was bugged. Over time I came to recognize friends’ voices from a simple hello. One friend wryly chose the English name “Tom Sawyer” to identify himself.

“Tom” was on the right track: Humor is one of the few plausible antidotes to the insidious workings of China’s security machine. What other reaction could there be to the inept security agent who, when confronted, claimed he had been dispatched by a mysterious stranger to follow me and deliver a gift of chocolates? (The candy never materialized.) Men with walkie-talkies followed me shopping and to the health club.

The Mercedes-Benz With Black Windows

State security goons routinely tail reporters in Beijing by car, motorcycle, bicycle and on foot, with lookouts posted at major overpasses and intersections. After many months of omnipresent and often heavy-handed surveillance, I began to recognize the faces of different agents responsible for various locations.

Some agents were elderly, some young. Most were male, except for a sharp-eyed fifty-ish woman posted on an overpass and a young woman who followed a Chinese-speaking Japanese friend to my compound several times. The unwanted company didn’t take much observation to detect. Around June 1990, just after the first anniversary of the Beijing massacre, I became aware of the persistent shadow of a Mercedes-Benz sedan in my rear-view mirror. The car changed colors and models, but in the beginning it was always a gleaming Mercedes and the windows were always black. Remembering similar tales from other correspondents who had been followed, I would occasionally conduct a crude test by pulling off to the side of the road.

My followers would do the same, usually hanging back by several car lengths. As I turned back onto the road, so would the Mercedes, nosing slowly but with a deliberate, shark-like motion into my wake. Subtlety was not a priority.

Security to Some Only a Nuisance

On the contrary, conspicuousness appeared to be part of the desired effect. Some correspondents disagreed, viewing China’s undercover army as more inept than sinister. Either way, the sum effect of surveillance was a creeping claustrophobia that intensified with time.

At first the monitoring was merely a nuisance. In moments of vanity or the effects of too many spy novels I even tried to take the extra attention as a compliment. In fact, I was a novice reporter, with far less experience and no better contacts than many other resident, Chinese-speaking foreign journalists.

The only distinguishing feature in my résumé might have been my chance enrollment at Beijing University from 1988 to 1989, at the height of the student-led democracy movement. It was at that time, when Chinese students and citizens were most receptive to foreign journalists, that I made the transition from student to reporter.

This personal metamorphosis was intensified by the sense of elation shared by many foreign journalists at the time, who were moved and sometimes overwhelmed by the changes they were witnessing. During the 1989 protests, Chinese students and marchers hailed the foreign press as a mouthpiece for their cause. This was only natural in a country where the concepts of press and propaganda are inseparable. Western reporters were instantly welcomed and sometimes literally shoved to the front of crowds.

“Make way for the journalist!” shouted a worker in late May, when a reporter tried to push through crowds to talk to soldiers barred from advancing on Tiananmen Square by incensed citizens. The crowd immediately parted.

The contrast after the crackdown was dramatic. During the demonstrations, foreign journalists were given constant access and frequently summoned to impromptu press conferences. After June 4, 1989, we were not only shut out but feared, lied to and even classified as unfriendly. One Western reporter caught sight of an official form handed out to Chinese interviewees in 1991—presumably by the local Foreign Affairs office—that ranked foreign journalists by name from “friendly” to “prejudiced,” with several degrees in between.

To the hard-line Chinese government that had crushed the movement, we were no different from spies. To students and liberal officials, we represented risks that many were and are still willing to take. Government repression has had the ironic effect of increasing information leaks by those infuriated with the present regime and undaunted by state security’s watchful glare. Internal policing appeared to have intensified following the collapse of Soviet bloc Communism, which internal Chinese propaganda attributed to lax political control.

Surveillance Begins on Leaving Compound

Surveillance brings with it a sequence of tics and gestures that, once learned, will always catch the eye. Leaving one of the walled compounds where all Beijing-based foreign journalists must live would trigger a daily ritual that never failed to infuriate me. The ritual began with the craned necks and outstretched hands of watchers posted at the gate as they reached for the telephone to report my departure.

Next came the gleam of metal on an overpass as a plainclothes agent whipped out a walkie-talkie to report my progress. Avoiding the overpasses didn’t help. At key intersections throughout the city such as Dongdan and Dongsi, a telltale bobbing motion identified more plainclothes police as they hunched over to speak into lumpy breast pockets or little black bags.

The monitoring didn’t end on the street. For weeks on end, my telephone would ring every time I walked through my front door. No one was ever on the other end. On several occasions, the UPI office telephone line cut out abruptly at the mention of sensitive names or topics.

In a village which sits amid mountains known as “Long Hills,” a woman sifts wheat. Photo by Stan Grossfeld, The Boston Globe.

‘Like a Sickness…Now It’s Back’

The suffocating paranoia was compounded by frustration that the surveillance was taking effect, causing some contacts to shy away or to ask nervously if I had brought my “tail.” One evening I emerged from a government official’s home to find a surveillance van parked ostentatiously in the narrow alley outside. The van’s dark windows and long directional microphone attached to the roof gave it the look of an alien predator stalking the crumbling back alleys of Beijing. The official nevertheless continued to see me.

One Beijing teacher aptly likened the fear of China’s security apparatus to a long-dormant disease. “It’s like a sickness,” the teacher said on a winter night in 1989. “We all used to have it in the old days, and now it’s back.”

The moment the teacher finished the sentence, there was a prophetic knock at the door. We both froze as a friend answered the apartment door and fended off an inquisitive building monitor, who had allegedly come to “collect the water bill”—at 8:30 p.m., after seeing me park outside and walk upstairs.

The harassment experienced by Western journalists naturally pales beside that heaped upon Chinese dissidents and ordinary citizens, who suffer a stream of petty indignities designed to break the spirit. Having the freedom to leave, I was less fatalistic than the Chinese I knew and lacked the sense not to fight back. I never grew accustomed to the idea of being watched, even knowing that the sole purpose of the act was to intimidate and disrupt.

Interview Requests Rejected or Delayed

The most damaging effect of the Chinese government’s treatment of foreign journalists is that it breeds the very hostility that authorities assume in the first place. The foreign correspondents I knew in Beijing were experienced professionals who had not traveled to China bent on opposing the government, much less subverting it through “bourgeois liberalism,” as Chinese propaganda claims. Since Tiananmen Square, the government has cast Western journalists and Americans in particular in the roles of hostile adversaries. A brewing U.S.-China trade dispute and recent American coverage of the sensitive topic of Chinese prison labor exports has further dampened official willingness to receive American reporters.

The reluctance surfaces in countless petty ways. Interview requests in the capital often are turned down or granted only after delays of weeks or months. One American journalist was unable to get the interviews he wanted even with the intercession by the Chinese Foreign Ministry, which has become increasingly aware of foreign journalists’ frustration. When granted, interviews can be grinding tests of patience, often preceded by a lengthy, prepared “introduction” to which the reporter is expected to listen without interrupting.

No Big Problem, No Small Problem

One typical interview that comes to mind is a 1990 meeting with provincial officials in Anhui, one of China’s poorer provinces. I was traveling with Dan Southerland, former Beijing correspondent for The Washington Post, and after much reluctance local bureaucrats had agreed to meet with us to discuss Anhui’s economy and other topics. Unlike more urbane bureaucrats in much-visited cities such as Shanghai, the Anhui officials appeared unaccustomed to speaking to foreigners and distinctly ill at ease.

The meeting yielded no useful information, save a heap of unconfirmable statistics on Anhui’s economic and agricultural triumphs. At least five senior provincial officials sat around a drab room in stuffed armchairs, staring uneasily into the distance, and declining to answer even the most innocuous questions. As the would-be interview succumbed to the pressing inertia in the room, Southerland tried one last desperate question: What was Anhui’s greatest social problem?

Silence. An official from the provincial planning commission finally broke it with his reply: “Anhui doesn’t have any large social problems.” Southerland persisted: What was the largest small social problem? The straight-faced answer was predictable: “We don’t have any small social problems.” End of interview. The relieved officials were in such a hurry to leave the room that one left his glasses behind on the table.

Same Scenario In Other Places

I spent two and a half years in China plagued by the sense that I wasn’t reporting effectively due to scenarios such as the one above, which was to be played out in similar rooms in many other Chinese cities. It is simply not possible to report accurately on the Chinese countryside while under local supervision. The most enlightening trip I made outside Beijing was a 24-hour sojourn to a village in Jiangsu in early 1990, accompanied by a Chinese friend. The Chinese economy was still reeling from an austerity program imposed in 1988. Millions of enterprises had been shut down or were operating at half capacity, but the effect was difficult to gauge under the usual constraints on the foreign press.

On a narrow dirt footpath cutting through the village, we met a retired man who had just withdrawn all his money from the bank and stashed it under his mattress. The reason he gave was that he “didn’t trust” the bank, which had recently run out of money. In the center of town, male workers idled by production halts and rural factory shutdowns sat on their front stoops tending babies.

Turmoil Feared More Than Authority

The peasants in Jiangsu were sarcastic and cynical toward the government, yet by no means on the brink of revolt. Many invoked the traditional Chinese fear of chaos, or luan, saying they preferred authoritarian rule to social turmoil.

Such encounters offered rare and unfettered glimpses of life in a Chinese village that would have been impossible under the required supervision. Official trips to the countryside are always chaperoned, preventing spontaneous conversation. During a visit to a village in Sichuan last March, a local official hurriedly waved me away from the sole peasant who called out a greeting, explaining, “Don’t mind her. She’s mentally ill.”

An Incident Shows Need for Caution

Under the circumstances, how can foreign journalists get stories out without compromising their Chinese sources? There are no ground rules, and each correspondent must find his or her own equilibrium. I personally found that some of the best stories I encountered in China could not be written because they risked endangering others.

An incident that occurred toward the end of my stay confirmed that my caution had been warranted. Less than a month before I was to leave Beijing, two men from a research institute under the Ministry of State Security approached both me and James Miles, the BBC correspondent, in what appeared to be an attempted setup. The men claimed at first to be seeking cooperation with “foreign scholars” on a private social survey. A second conversation yielded a persistent interest in the CIA and assertions that “certain Western journalists” were intelligence agents. At the third and final meeting, one of the two men became impatient and gestured angrily at a copy of Newsweek that featured a story on Chinese labor camps.

“Don’t you understand?” he exploded. “We can get you much better information than that, but we need money.” I explained that I had no interest in their “survey” and was unable to help them. Such a heavy-handed attempt to incriminate a journalist seemed almost too obvious to believe.

For all the time spent chafing under the irritation of surveillance, surprises popped up when I least expected them. One of the most unpleasant took place on a cool afternoon last October.

I had the day off and spent most of it visiting a Chinese family. Undercover police on motorbikes had followed my car on the way to their home, but appeared to have lost me after I took several wrong turns through a bewildering maze of alleys. Perhaps they took my bad sense of direction for deviousness.

No one was in sight when I parked and entered the building. Yet several hours and innumerable cups of tea later, when the family stepped outside to see me off, someone was waiting. A gray-faced man holding a poorly concealed video camera appeared out of nowhere, pointed it at us and abruptly rounded the corner.

Less than a minute later, I nudged my car around the same corner. The alley was empty. The encounter had been like a hallucination, and yet it had happened—for a moment, the fisheye lens of a police state had stared us in the face.

“I don’t give a damn,” my Chinese friend said when I mentioned the security agent. For all his nonchalance, the sudden intrusion had the force of a brutal slap in the face.

Fighting Silence Is Difficult War

Two months later, ensconced in the comfort of home in California, the brutality of that slap came back to me in a passage by Ryszard Kapuscinski, a Polish journalist who spent many years in Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East. He wrote in “The Soccer War”:

“Today one hears about noise pollution, but silence pollution is worse. Noise pollution affects the nerves; silence pollution is a matter of human lives. No one defends the maker of a loud noise, whereas those who establish silence in their own states are protected by an apparatus of repression. That is why the battle against silence is so difficult.

“It would be interesting to research the media systems of the world to see how many service information and how many service silence and quiet. Is there more of what is said or of what is not said? One could calculate the number of people working in the publicity industry. What if you could calculate the number of people working in the silence industry? Which number would be greater?”

The same applies to China. Until restrictions loosen, foreign journalists in Beijing are in the unenviable position of trying to defy the silence industry without endangering those who choose to speak. It is not an easy task.

Sarah Lubman began stringing for the Hong Kong Standard in 1989, then was hired as a freelancer by The Washington Post. After the Tiananmen Square suppression, UPI hired her full-time as a “super stringer,” a polite term for doing the work but not getting the pay of a regular correspondent. In two and a half years with UPI she also filed stories to National Public Radio, The Boston Globe, the San Francisco Examiner, and The Chronicle of Higher Education.