“It is my judgment that Mr. Johnson wants to hold control in his own hands.”—Strout.

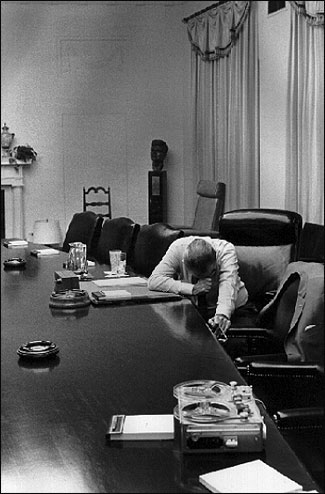

Photo by Jack Kightlinger, courtesy of the Lyndon B. Johnson Library Collection.

[This article originally appeared in the September 1966 issue of Nieman Reports.]

…I can see Coolidge riffling through the pile of written questions, deciding which he would answer. On one occasion Charlie Michaelson, I believe it was, got a dozen correspondents to ask the same question! Would Coolidge be a candidate in 1928?

Coolidge looked at the first question and put it aside. He looked at the next! Put it aside. He went on from the third to the eleventh. At the twelfth he paused, read it, and went on dryly, “I have here a question on the condition of the children in Poland. The condition of the children in Poland is as follows…” He then talked for several minutes and concluded, “That’s all the questions.”…

Every President of modern times has made use of press conferences, adapted them to his peculiar style, and carried them on. It was General Eisenhower, unfortunately, who changed their whole character by admitting live radio and television coverage.

I yield to nobody in my admiration of radio and TV. In their own field they are superb. But there are places where I would not admit live radio and TV coverage. The effect at White House press conferences is to make us all reluctant, unpaid, Hollywood actors, ending all intimacy, and encouraging the exhibitionists. As every reporter knows, it is not the first question in a group interview that gets the answer, it is the second or third follow-up question. But with TV the question is asked, it is answered or evaded, and that’s that. The reporter has had it.

Let me make my position plain about the relationship of the Washington press corps to the President. It is true that I have a jealous regard for the prestige of my profession. But I hope I am reasonably objective about it. I think more doors are open in Washington, and more information available in spite of carping and criticism, than in any other world capital. And I am aware, too, that the relationship of press to President is apt to be an adversary relationship: The White House wants us to have the favorable news, we are after all the news.

I do not find fault with this relationship. I do not want the press to be a smirking sycophant, nor do I want it to be a snarling, snapping prosecutor. (In my lifetime I have seen it take on both characters in Washington.) But the presidential press conference itself is very much what the President makes it. It is an honorable, a salutary and, I think, a necessary adjunct to our government, and I do not like to see our profession let it wither on the vine without a protest.…

Roosevelt had just under 1,000 conferences. Mr. Truman, if my figures are right, had well over 300; General Eisenhower cut the number down to 200, and President Kennedy in his bright 1,000 days had a conference about once a fortnight.

Alas, this tradition has not continued in recent days. President Johnson has been one of the most accessible men to the press of any President, that is, in informal gatherings, meetings with individual bureau chiefs, or tips to favorite correspondents. But as for formal press conferences, I can only figure that he had nine last year. So far in 1966 he has held only a few.

But in the United States the executive is all rolled into one. No other democracy has an elected leader with such enormous, such awful power. It is the power of peace and war. There is no question time in Congress. This is my chief argument—I think it is terribly important that somebody on behalf of the people meet the President face to face and ask him what he’s doing. Not in a hostile or challenging manner. But just to make his position clear.

Where a modern President forgoes the regular press conference—and I acknowledge it has many faults and is time-consuming and even irksome—you are apt to get a substitute; it’s funny how all these metaphors run to hydraulics: government by leak, information by seepage, or let me call it news-ooze.…

News by osmosis may be successful for a while, but in time it produces, I believe, a credibility gap; the kind of gap which some think they see at present. Gen. Maxwell Taylor, presidential adviser, wants to mine Haiphong Harbor; we ought to be able to ask Mr. Johnson about it.

There are evidences that the President is of two minds about regular scheduled press conferences. On March 13 and on March 20 a year ago he promised “at least one press conference a month.”

Why hasn’t he held them? In a celebrated interview not long ago Bill Moyers attacked the radio-TV press conference as a “circus,” “televised extravaganzas.” Well, for heaven’s sake, who made them that way? Who brought television into the press conference? I believe TV does a superb job (and radio, too, of course). But I think television should be outlawed in three places, anyway—in the Supreme Court, in the nuptial bed, and in White House press conferences.

Actually I think the thing goes deeper than Bill Moyers’ explanation. President Johnson, in my estimation, does very well at formal press conferences when he has held them.

It is my judgment that Mr. Johnson wants to hold control in his own hands. His ideal is a private audience with selected reporters where he can talk and they can listen, and nobody asks too many unexpected questions. It is a habit, an approach, an instinct that he cannot break. He discovered in the Senate that when he disclosed his views he limited his freedom of choice, and his opponents thwarted him. He is a very complicated man. He is divided about the press: He affects to decry it, and reverences it; he patronizes it, and he writhes under it; he will overreact in an extraordinary way to woo some individual reporter.

Yet the President cannot leave it alone, what it is saying, what the polls are saying, what his rating is. Theoretically, I am sure, he has faith in the ultimate give-and-take of opinion in a free democracy, but he can’t overcome a lifetime of trying to manipulate the scales in his favor.

And this brings me to my conclusion. A reporter in Washington can become a kind of dramatic critic to a tremendous show in which the President inevitably is the central character. Woodrow Wilson was one of our greatest Presidents, yet he had a tragic flaw, his Calvinistic rigidity which betrayed him in the end. By making concessions he could have crowned his life by having us join the League of Nations. He couldn’t. We didn’t.

And now President Johnson. I believe he has in him a mighty yearning for success, and unquestionable elements of greatness, but there is a testiness, a secretiveness, a sensitivity about him all expressed in his unwillingness to accept the normal discipline of a formal press conference; a perfect tool for him to fill the credibility gap, if he were prepared to use it.

Well, the time may come when he will be glad to use it.

Mr. Strout is Washington Correspondent for The Christian Science Monitor. This is an excerpt from the George Polk Memorial Lecture he delivered in New York.