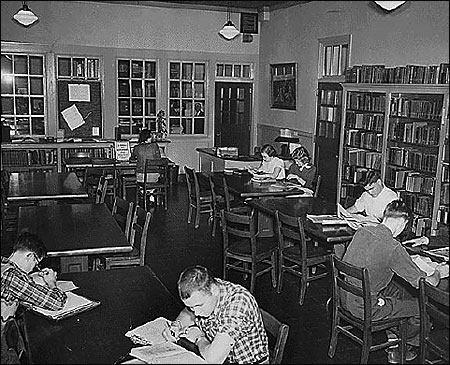

A school library in Farmville, Virginia. From plaintiffs’ exhibits—photographs filed in Dorothy E. Davis, et al. versus County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, Civil Action No. 1333. Photo courtesy National Archives and Records Administration’s Mid Atlantic Region, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

[This article originally appeared int he April 1962 issue of Nieman Reports.]

“Have you read the history of Prince Edward County?” belligerently demands the businessman in button-down collar. “Why, one of the bloodiest battles in the Civil War was fought right over here at Sayler’s Creek.” He motions over his shoulder with a pencil, but all the visitor can see is a modern wood-paneled wall. Then, in the sluggish way residents of Southside Virginia have of figuring the passage of time, he adds, “These people are only a couple generations away from it.”

Down the street, John C. Steck, Managing Editor of the semiweekly, segregationist Farmville Herald, checks some proofs brought to his desk. Steck represents Farmville on the Prince Edward County Board of Supervisors which, back in 1959, cut off all funds for public schools when the county faced the threat of court-ordered integration. One of the original defendants in the set of cases which produced the 1954 desegregation decision, Prince Edward County today is the only county in the United States without any public schools.

Why was this desperate, last-resort action taken?

Listen to Steck:

“We’re fighting for states’ rights,” he explains softly. “We’re opposing federal usurpation of power and an illegal court decree.”

Around the corner, in the shopping district of Farmville’s Main Street, E. Louis Dahl swivel-hips between crowded tables and counters in his Army Goods Store, eagerly showing customers the latest in sporting goods, hardware and long johns for early morning plowing. A copy of The Citizens’ Council, the segregationist publication from Jackson, Mississippi, rests on a counter of sweatshirts near a potbellied wood stove. Dahl serves as treasurer of the Prince Edward School Foundation, the group which has been providing private schooling for the white children since the shutdown of public schools.

From the start, the Foundation has been pressed for finances. Sometimes there have been enough pledges on hand—but hard coin?

“What do you want to know how much cash we have collected for?” Dahl asks, his eyes narrowing. “What kind of a story are you going to write?” And then, “I don’t have to tell you how much money we have if I don’t want to—and I don’t want to.” He turns quickly away and begins chatting with a customer.

This, tragically, is Prince Edward County, Virginia, a small, rural, pine and tobacco county 65 miles southwest of Richmond, 50 miles east of Lynchburg, in the “black belt,” with a population of about 18,000 divided roughly half white, half Negro.

Virginia’s “massive resistance” as a state program of last-ditch, close-the-schools opposition to integration died in 1959 after adverse court decrees and a bitter special session of the General Assembly. But “massive resistance” still lives today as a local option program and Prince Edward County has exercised this option.

My topic is “massive resistance,” and I am expected to tell the story of Prince Edward County. Should I tell you what you want to hear? Should I tell you what any national audience expects to hear? Should I don libertarian lace, pluck delicately at the Harvard harp, and chant about the inequities of a segregated society?

As a Nieman Fellow at Harvard, I have found too many others doing this sort of thing. The Lynchburg newspapers, with the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, were the only Virginia newspapers to oppose from the first Virginia’s plunge into “massive resistance.” And from my desk at Lynchburg I have written critical editorials on the Prince Edward situation.

This approach, however, does not appeal to me here.

Nor will I attempt, as some sensitive Southerners have attempted, to foist on you a “true account,” for most of what is said in condemnation of the South, of Ol’ Virginny, is lamentably true.

But this brings me to my purpose, to my one complaint about Harvard, to the one tin slug that I have found amid a chestful of treasure. Let me examine it with you.

I do not object so much to what is said around the Old Yard as to what is sometimes not said, not so much to what is charged as to how it is charged. More than this, I do not cringe so much at the criticism of the South which tumbles from some lecterns as at the response which this criticism invariably elicits. Progressive education seems to have replaced learning by rote with learning by reflex. Tell an anti-South joke and students automatically roll in the aisles; cite an uncomplimentary statistic and raise a chorus of condemning hisses.

Barry Goldwater asserts that he has found a groundswell of conservatism on the campuses. I have not. On the contrary, the gathering monolithic front of campus liberalism, threatening to become doctrinaire, blunting the sharp point of challenge, should concern us all. I fear that questions wilt in the mind when lips offer only an agreeing, supercilious snicker.

In a word, I think that Harvard’s response to the deep problems of the South is wrong. And, for the purposes of this article, I think that this complaint can probably be expanded. I think that the Northern response, when it consists only of snickers and hateful epithets, is also wrong.

So, my plea is for understanding. Let me address myself now to my subject, to “massive resistance” and Prince Edward County; also, let me suggest the sort of response, or approach, that I think this topic should receive.

I speak now of patriots, of Jefferson and Madison, Mason and Monroe, and of Patrick Henry, and of military heroes, of Washington and Jackson, Stuart and Robert E. Lee. I ask you to listen, as Prince Edward County has listened, to chilling Indian yelps, to British drums and Yankee bugles. I ask you to feel, as residents of Prince Edward have felt, the surge of defiance which freed a loose bundle of colonies from the oppressive grip of a powerful empire—and a later surge which set an incredible Confederacy, stubbornly disunited, athwart the path of a nationalistic juggernaut and the rising tide of worldwide humanitarian history. Join Prince Edward’s Phileman Holcombe in the French and Indian War. March off with Captain John Morton from Prince Edward Courthouse to engage Lord Dunmore’s forces at Portsmouth, then to turn northward to join Washington’s army for Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, Germantown and Valley Forge.

Watch in horror as the Gray retreats; see the Blue come inexorably on. Realize that 14 miles from the Prince Edward County line, at Appomattox, the Confederacy crumbled. It was nearly a century ago, to be sure, but if you lived your life in Prince Edward County, you could climb to any hilltop, shut your eyes, and still feel the terrible rumble of Sheridan’s cavalry and still smell the stench of gun smoke in the air.

I ask you to stand now, if you will, with Prince Edward County through a history both rich and grim, a history scarred by slavery, fired by a rebel spirit to a brave defense of a political anachronism, state sovereignty.

To understand Prince Edward’s feeling on the race question, one must go back to 1755 when a list of “tithables’’ (taxables) showed that Abraham Venable owned five slaves, Richard Wilson owned seven slaves, and Colonel Randolph owned 27 slaves, and to November of 1768 when “a parcel of choice slaves, house carpenters, sawyers, house wenches and ground slaves” was offered for sale at public auction.

To understand the county’s defiant spirit, one must listen to the most famous rebel in American history, Patrick Henry, who, as a resident of Prince Edward County, traveled to Richmond to oppose ratification of the federal Constitution by Virginia in 1788.

“Slavery,” he observed solemnly, “is detested. We deplore it with all the pity of humanity.”

But abolition? Henry made his prophetic stand clear:

“Emancipation is a local matter not to be left to Congress.”

To understand Prince Edward’s feeling about state sovereignty, one must attend the public rally held at the courthouse on March 9, 1861. As other communities were beginning reluctantly, almost timidly, to consider secession, this mass meeting voted overwhelmingly for it. Reports show that on a voice vote all shouted “aye” but one who voted “no,” and an embarrassed county has not recorded his name.

“So,” the Richmond Enquirer said of the meeting, “Prince Edward may be set down as perhaps the most unanimous county for immediate secession in the state.”

Also, one must go back to a warm evening in early April of 1865 and ride wearily to the crest of a Prince Edward hill with General Robert E. Lee. Here he looked down on the losses he had suffered in the Battle of Sayler’s Creek and said huskily: “My God! Has the army dissolved?” When his scattered troops saw him, astride his horse, carrying a battle flag, they came to him in what historians have called the last rally of the Army of Northern Virginia. Three days later, a few miles on, Lee surrendered.

To understand the temper of Prince Edward’s resistance to school integration, one must also understand recent history. In 1951, before the NAACP filed its integration suit, the county went deeply in debt to begin construction of an ultra-modern $900,000 school for Negroes which far surpasses any facility for whites. Negro students had spent a full year in it when the 1954 decree came down, discarding the separate-but-equal doctrine which had formed the foundation of the South’s social structure.

In May of 1954 the high court announced its decision. In July the Prince Edward Board of Supervisors adopted a resolution of “unalterable opposition” to integration.

At this point the story becomes a blur of legal battles, battles still being fought, of mass meetings, affirmations and appeals. What is vital now is to understand that all public schools were shut down in 1959 when court delays ran out, that since this date white students have been attending classes, first in makeshift quarters including an old, abandoned blacksmith’s shop, now in a newly constructed private school, that Negro students have been attending no schools in Prince Edward, but have only participated in irregularly scheduled “morale building” sessions.

For the first year, the private school for whites operated on voluntary contributions; for the second year, it managed by charging tuition and inviting parents to apply for both local and state-backed tuition grants; now, in the third year, a federal court has enjoined the use of public funds, and I have at hand a letter, dated December 2, 1961, which solicits contributions toward a goal of $200,000 to keep the private school going until June. There is, moreover, a case now pending in federal courts to determine whether, under the state constitution, Virginia must maintain public schools in Prince Edward County.

Tie these developments together and this is Sayler’s Creek. Appomattox lies just over the hill.

And, briefly, this is the background for Virginia’s “massive resistance” and the story of Prince Edward County. If I have dwelt more on the past than the present, it is because Virginians involved in this story dwell more on the past and because, if we read in the daily press of limbs and branches, the roots also lie in the past.

Make no mistake: I do not intend all this as a defense, simply as an explanation of a story unfolding in the old Southern, tragic tradition. In Prince Edward County, men today summon courage to defend false ramparts and hollow ideals; they swing swords for a parochial “sovereignty” which was surrendered with Lee’s sword long ago; they hoist battle flags emblazoned with cries of patriots of an earlier day who would, if they had breath today, denounce the blasphemy.…

Despite jet flights and nuclear energy, Cape Canaveral and Redstone Arsenal, the rural South remains pretty much a legend of gray legions and silver trumpets, of crinoline and gracious living, of beauty and chivalry and lost causes. Its history is half romance, and its secret god is James Branch Cabell’s “demi-urge,” the myth-maker, the dream-weaver.

The Romantic poet Lord Byron once wrote of lovers parting:

If I should meet thee

After long years,

How should I greet thee?—

With silence and tears.

Who knows—we can all only surmise—but I suggest that the poet’s answer would guide the patriots. Let me suggest, further, that the South’s story today is more tragic than humorous, that it deserves serious, even sympathetic attention and—to my theme—that there is less historical justification for supercilious snickers than for poetic tears. As the South renews its struggle to enter the mainstream of American life, as men of good will grope for solutions to cataclysmic social problems, I would be less than true to my region if I did not urge, at least for occasional use, the poet’s answer on you.

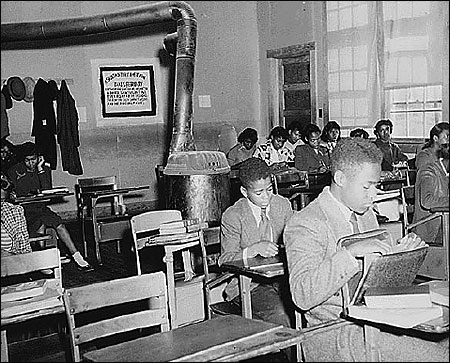

Miss West’s English 9 class in Moton, Virginia. Defendants’ exhibits—photographs filed in Dorothy E. Davis, et al. versus County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, Civil Action No. 1333. Photo courtesy National Archives and Records Administration’s Mid Atlantic Region, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

John A. Hamilton, a 1962 Nieman Fellow, is Associate Editor of The Lynchburg (VA) News, where his editorials have been vigorously critical of the Prince Edward County school situation.