“Television by its nature has to move on…it cannot explain or expound.”—Muggeridge.

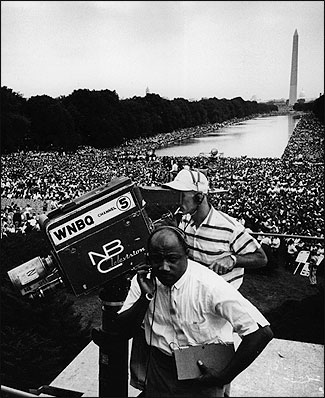

Civil rights march on Washington, D.C., 1963. Photo courtesy of the Still Picture Branch, National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

[This article originally appeared in the October 1959 issue of Nieman Reports.]

The thought occasionally occurs to me that if the present obsession with television and radio continues, the written word may become unnecessary, irrelevant and obsolete. Mankind may develop square eyes, or generate a single square eye in the center of the forehead. As what Professor J.K. Galbraith has so aptly and ingeniously called “The Affluent Society” goes on developing, the increasing leisure thereby made available may be devoted more and more to watching television.

Over considerable areas of the world, print has already largely abolished thought. I do not see why viewing should not in its turn abolish print. However, unless and until this happens, we have the two media existing side by side. I was going to add “in competition,” but was pulled up by the thought that the masters of the printed word, the newspaper and magazine proprietors and publishers, have prudently insured themselves against television losses by going into business themselves whenever possible, thereby becoming also masters of the visual image.

In my own country, in England, this has recently happened. We used to have a monopoly in the hands of one of the most singular institutions ever to exist since the Holy Roman Empire. I refer, of course, to the British Broadcasting Corporation, which may perhaps be described as begotten by John Knox out of the Bank of England with the Fabian Society intervening. Now this organization—next, of course, to the monarchy—is most dear to me. The sentiment unhappily is not reciprocated. I have in fact been cast off, excommunicated with bell, book and candle, as unfit to contaminate its virtuous little screen. (Nonetheless I continue, like a brainwashed Communist, to venerate my chastisers and to applaud the logic of my chastisement.) The only reason I mention these little incidents is to make the point that if we are talking of freedom of expression, television lends itself even better than newspapers to utter rigid control in the interest of orthodoxy and conformism. This should be kept in mind.

We have now as a matter of fact, in England, what is laughingly called Independent Television. This is presided over (at any rate nominally) by a former permanent undersecretary of the Foreign Office, who is apparently always available for such posts as these. Now apart from this fortunate circumstance, the actual ownership of the Independent Television companies is much enmeshed with the ownership of newspapers. For instance, that most famous of all newspapers, the News of the World (into whose offices I used enviously to peer when I was editor of Punch, thinking of all the scoutmasters on “serious charges” who were going to be immortalized in its columns), has its slice; so have many others. The ones that haven’t, like the Beaverbrook newspapers, are forced to solace themselves by complaining in the most high-minded manner imaginable of the large illicit profits of Independent Television and of the degrading character of its productions. Now in the United States, Australia and elsewhere in the free world, a similar situation prevails. Thus commercially speaking, there is no more competition between television and press than there is between Time, Life and Fortune.…

Even so, there is no possible doubt that the two media, the visual image and the printed word, have profoundly influenced one another. Take the case of the evening newspaper. In London we have three, each priced twopence-ha-penny. The office toiler as he makes his way homewards, packed tight in buses and in underground trains, is increasingly disinclined to buy, let alone try to read, an evening newspaper, when on his arrival in the bosom of his family he will see on television the evening news for nothing. When I add that even public houses—as sacred in the English way of life as women’s clubs are in the American—have suffered a like deprivation from the same cause, you will understand the magnitude of the threat. Morning newspapers are less afflicted. But they too have been forced to take account of the fact that news may well have lost its bloom of television by the time they print it, that prized features may have wilted because of some tedious discussion program the night before. That even the seemingly secured territory of the obituary has been invaded, leaving them only with editorials (which, as Sir David Eccles remarked the other day with some notoriety, “nobody reads”) and births, deaths and marriages, which can scarcely be regarded as circulation-builders or advertisement winners.

What has been the reaction of the newspapers to this, from their point of view, very serious state of affairs? Oversimplifying, I’d list three.

First: attempting to go with the television tide by, for instance, using television personalities as columnists and giving a massive coverage to television shows, to gossip and controversy about television.

Secondly: attempting to provide a rival attraction to television by neglecting news stories and concentrating on frivolous human-interest themes—by, in other words, becoming a magazine.

Thirdly: attempting to meet the challenge by producing more of what television cannot by its nature produce or produces only inadequately, superficially and fleetingly; I mean comment, exposition, the search for the meaning and significance of the contemporary scene apart from its mere presentation.

My own preference, I hasten to say, is point three, but before going into that a little more fully, let me say a little word about one and two. With regard to the journalistic exploitation of “televisioniana,” it’s a rather barren pursuit. The television personality, in any other respect, is seldom interesting and is, happily, (with one or two notable exceptions) short-lived. When, in a very minor way, this fate befell me, I found myself billed in newspapers as “a television personality.” A controversial figure, I wrote even more foolishly than usual as a consequence. The only noticeable result of this strained situation was that it became difficult for me to engage in clandestine pursuits—like adultery—for the very simple and cogent reason that in hotels and other resorts where adulterers consort one was immediately recognized, to the embarrassment of all concerned. You may consider that this is one of the few moral justifications for the invention of this terrible thing, television.

Nor, as a matter of fact, in my opinion, can newspapers sustain themselves by providing information about television, which in any case specialized magazines, in England and in America, exist to provide. The viewer views—and having viewed goes to bed—waking the next day to view again—and there is no slack to be taken up in that majestic process.

As for newspapers seeking to be more frivolous, inconsequential and fatuous than television, they will, it seems to me, always be beaten in that contest. As “escapism,” as the soporific, the little screen, making no demands on its addicts—requiring of them only an empty stare—will always win. Compared with it, even tabloids are as ponderous as Kant and even Time and Der Spiegel are as tough reading as Hamlet.

Then to the third point. Here I think there are some grounds for what our Foreign Minister, Selwyn Lloyd, is always describing as “reasoned optimism.” There is so much television cannot do, and so much that the printed word can and always will be able to do. With all its terrific impact, television is little listened to. During the time that I used to appear on it fairly regularly, I never had one single instance of anyone recalling a thing I had said. Television by its nature has to move on; it can mount useless discussions and interviews, but it cannot explain or expound. What, for instance, a brilliant British journalist like Alistair Cooke does in the way of presenting the American scene in the columns of the Manchester Guardian—with all his gifts, he cannot begin to do on television (or even on sound radio).

Thus, it might be that the television cult will rescue journalism from the triviality and sensationalisms which have so corrupted it in recent years. It might force journalism to return to an earlier and better tradition by siphoning off the excrescences, the cheesecake, the gossip, the melodramatic overplaying of news stories, simply because of the happy chance that, in this field, television is unbeatable.

Malcolm Muggeridge, formerly Editor of Punch, spoke at the International Press Institute assembly in Berlin in May. This is an excerpt.